Every week, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, searching through the haze…

FANTASY VS. REALITY

Almost everyone in the art world these days feels unmoored. The disorientation is partly the effect of sheer volume. Even if one restricts their view to New York alone, the city hosted so many gallery shows, art fairs, auctions, and one-off events in May 2023 that living through the month felt like weathering a fever severe enough to induce hallucinations.

The state of the market is shifty, too. The consensus is that the spring evening sales signaled the start of a long-anticipated correction. But good luck finding a cogent explanation for what’s up and what’s down that’s neither reductive nor abstruse. Doomsayers and the panic-stricken see the ghost of the 2008 recession lurking around every corner, while moderates think we’re closer to the barely remembered belt-tightening of 2016, and others argue that the 2020s are so economically, politically, and culturally novel that historical comps are powerless to frame the current state of affairs.

Gone as well is any dominant aesthetic or overwhelmingly favored group of artists. The demand for deeply personal figuration by artists of color has undeniably waned; it’s just that no one seems sure whether its sturdiest replacement is a new wave of abstraction, a contemporary update on the Baroque, a revival of Surrealism, a quantitative aesthetic, or something else entirely.

Basically, we’ve clearly kicked free of the most recent past, but we’re still waiting for a dawn bright enough to clarify where, exactly, we’ve landed next. Meanwhile, different factions of the art world see vastly different shapes in the gloaming.

It’s this lack of grounding in time or place that makes Los Angeles-based Adam Alessi’s practice feel so of the moment. And it’s the flight path of the 29-year-old artist’s career—as charted by Clearing, whose résumé for leading emerging artists to a new level has few equals—that will provide a valuable indicator of collectors’ and institutions’ preferences in this murky new era.

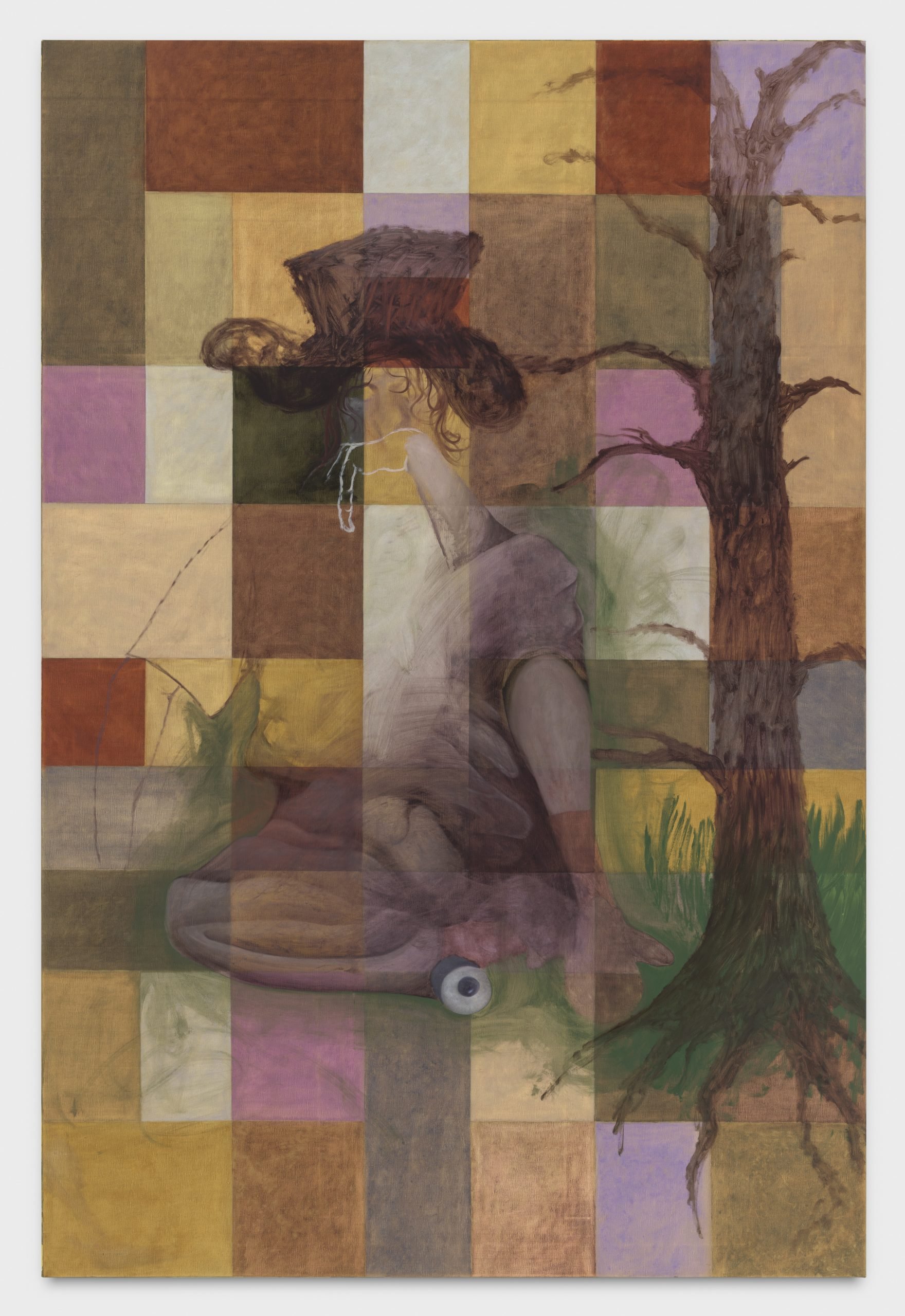

The scenes in “The Village,” Alessi’s solo exhibition at the New York flagship of Clearing (which stylizes its name in all caps and extreme spacing between letters), smirk at attempts to pin them to any definitive epoch, region, or culture. Often centered on wan figures with facial features indebted to Spirit Halloween witches and Carnival masks, the paintings and drawings evoke folklore without a clear origin point. His characters’ crushed top hats and tilted fedoras recall bygone bohemians, peasants, or pilgrims—unless you’ve lived in Los Angeles long enough to know how much rich hippies in Laurel Canyon and bearded East Side trust funders adore brimmed statement hats. The characters emerge from backdrops that vary between layered color fields and sketchy forests with occasional cottages, the latter of which could equally be visions of a pre-modern past, a timeless rural lifestyle, or a late capitalist effort to go back to the land because cities have failed us.

Adam Alessi, installation view of “The Village,” C L E A R I N G, New York, 2023.

© JSP Art Photography

Courtesy of the artist and C L E A R I N G, New York / Brussels / Los Angeles.

In short, don’t read too much into the wisps of Toulouse-Lautrec. Alessi admits that influence is in the mix, but in his mind, each image simultaneously represents anywhere and nowhere.

“I’d be disappointed if people could place it in 19th century Paris, because I’m not really interested in that,” he told me in one of Clearing’s ground floor galleries during install of “The Village.”

Clearing founder Olivier Babin said by phone that he and Alessi had already started discussing his New York debut while the gallery was winding down the lease on its inaugural space in Bushwick and hunting for its next headquarters in the city. While the artist began showing with Clearing in late 2021, this exhibition is the first solo outing at the gallery’s new home on the Bowery and only the second show staged there overall. (“Maiden Voyage,” a group affair that included work by every artist in the gallery’s orbit, closed May 21.)

“I wanted to start with a group show because it would have been unfair to everyone else to give the first spot to a new artist with the gallery, and also undue pressure on him,” Babin said. Beyond that one extraordinary circumstance, however, he had “complete trust” in Alessi’s work—and total conviction that it was time to introduce him to New York on a grand scale.

“First show, last show, it doesn’t matter. He deserves a show,” Babin said.

Yet “The Village” went on view at an unpredictable moment in the Empire City’s art world, as buyers and sellers alike try to recalibrate their expectations after a high-variance slate of spring sales events. In this context, Clearing’s 12-year legacy of shepherding young phenoms (from Harold Ancart and Korakrit Arunanondchai, to Meriem Bennani and Hugh Hayden) lends Alessi’s show a kind of unstoppable-force-meets-immovable-object dynamic. The tension is almost too appropriate.

Adam Alessi, The Walker (2023). © JSP Art Photography, courtesy of the artist and C L E A R I N G, New York / Brussels / Los Angeles.

WORLDBUILDING

Before Alessi’s own studio career took off, his ties to the art world proper were nonexistent. The strongest personal connection he had was a plein air-painting great uncle who he never actually met. His exposure to the establishment consisted of a few scattered childhood trips to the Getty and the Museum of Contemporary Art, and a couple of mass-market prints of Renaissance works hanging in his home.

He became a voracious image-maker in his adolescence. His commitment to creating visuals overrode his commitment to high school, he explained, especially once he started accepting freelance photography assignments. To graduate, he eventually had to take a summer course in design, where his traditionalist teacher forced the class to work out the basics with rulers and other manual tools.

“Back then for me it was hell. But now I look back on it, and I learned a lot about how to lay things out properly,” Alessi said.

That experience turned out to be his last brush with formal artistic training. His education ever since has been self-guided and free-ranging. “I was open to everything that I put myself in front of. That was my school. I’m trying to find things that no one has ever heard of,” he said of his reference points.

It took close to a decade before his DIY approach found traction in the L.A. art world, partly thanks to a side door he found in the city’s food scene. Alessi first got into cooking through a friend who went to culinary school, then landed what he called his “first consistent job” in the kitchen of Jon and Vinny’s, a beloved Italian spot opened by Angeleno chefs-turned-restaurateurs Jon Shook and Vinny Dotolo, when he was in his (very) early twenties.

The connection was auspicious on multiple levels. Shook and Dotolo have now been deeply entrenched in the L.A. art world for decades. In particular, Dotolo joined the Hammer Museum’s board of advisors in January 2022 and even curated a food-themed 2016 exhibition at the Los Angeles gallery M+B. Alessi, who today calls Dotolo “a great friend and a great collector,” fondly remembers a Jonas Wood work hanging in the kitchen at Jon and Vinny’s during his days on the payroll.

Adam Alessi, Chef (2023). © JSP Art Photography, courtesy of the artist and C L E A R I N G, New York / Brussels / Los Angeles.

Alessi spent the next several years living a double life in cooking and in art, with the bonds in one sometimes strengthening the bonds in the other. He split a garage studio with fellow rising L.A. artist Jan Gatewood for a time; he also co-founded Insect, an artist-run space in the city’s Frogtown neighborhood that staged a year’s worth of shows just before the pandemic. He eventually became a regular at Jonas Wood’s semi-legendary art-world poker game, alongside other Angeleno artists like Mark Grotjahn and Matt Johnson, dealers like Nino Mier and Blum and Poe cofounder Jeff Poe, and a rotating cast of major collectors, auction executives, and mainstream celebrities.

Trying to parse how these intermingling relationships buoyed his studio practice, and vice versa, is a textbook chicken-versus-egg dilemma. What we do know is that Clearing wasn’t the first gallery to take interest in Alessi’s idiosyncratic visual universe.

Mier, another dealer with a strong record for talent-spotting, showcased his work in a January 2020 group exhibition curated by Purple magazine editor-in-chief Olivier Zahm. A one-person show at Los Angeles gallery Smart Objects opened later that year. Solo booths at NADA House (with Zoe Fisher Projects) and Felix (with M+B) followed in 2021, before Smart Objects staged Alessi’s second one-man exhibition in spring 2022.

Not surprisingly, some of Los Angeles’s most influential young tastemakers caught the scent early in this progression. “I first discovered Adam’s work several years ago through Chadwick Gibson of Smart Objects and have been collecting the work since,” advisor and curator Jack Siebert wrote in an email. “I was intrigued by Adam’s attention to detail, but also frightened by some of the imagery. Adam invited me over to his studio, and I immediately became immersed in the wicked world Adam creates.”

Still, M+B’s Felix presentation turned out to be especially consequential. Babin didn’t just see Alessi’s work there for the first time; he bought a small canvas from the booth—the ultimate vote of confidence from a gallerist with an eye for emerging artists. “Once you’ve seen the work, you can’t unsee it,” Babin said.

The encounter wasn’t pure serendipity. Babin had been clued into Alessi’s work by their mutual friend Calvin Marcus, whose own steep ascent to the art world’s upper echelons has included nearly a decade’s worth of exhibitions with Clearing. At first, though, the impact of the paintings had more to do with their upside than their consistency.

“I might see five paintings, and four I wouldn’t care for, but one would be extraordinary. That’s the way I always look at work: How good can the best be, and what can be done to make sure everything is going to [level] 10?” said Babin.

Still, the exposure, the personal recommendation, and Alessi’s own virtues accelerated his eventual entry to Clearing’s roster. He and Babin started a dinner club together at the latter’s house midway through 2021. Within the gallery’s program (setting aside art fairs), Babin first curated Alessi into a group show that ran from November to December 2021 in the gallery’s Bushwick flagship. This was followed by appearances in three more Clearing group exhibitions in 2022: sequentially, one each in New York, Beverly Hills, and Brussels.

Alessi’s inaugural solo outing with Clearing opened only two months after the aforementioned Brussels group show closed. Titled “Cruiser’s Creek,” it consisted of just seven paintings and one small watercolor, all installed in the front section of the same Clearing venue. “The Village” debuted roughly nine months later.

Adam Alessi, The Village (2023). © JSP Art Photography, courtesy of the artist and C L E A R I N G, New York / Brussels / Los Angeles.

NO PLACE LIKE HOME

The current show’s title has multiple meanings. On one hand, “The Village” alludes to the strange enclave of characters in Alessi’s latest paintings. But he and Babin both say that it is also an inside reference to the Los Angeles art scene, whose recent portrayal as a global juggernaut in the art media belies a humbler, tighter-knit reality—one that Alessi’s rise also reflects.

“The art world is small in New York, but in L.A. it’s minuscule. The parts are almost touching,” Babin said.

To me, framing “The Village” as a distorted mirror of Alessi’s home bolsters a current in the work that dates back to at least his debut at Smart Objects. His practice plays with the Freudian sense of the uncanny: a subtle destabilization of something that at first seems deeply familiar, or conversely, the discovery of a subtle relatability in something that at first seems deeply unfamiliar. (“Uncanny” is the English translation of the German unheimlich, literally “unhomely.”) Freud’s argument was that, no matter which direction it is triggered from, this friction between comfort and discomfort wears away old assumptions and leads to new revelations.

Crucially, though, Alessi is very consciously playing with uncanniness in his work. Think of it as the camp uncanny: Goya or Honoré Daumier by way of The Rocky Horror Picture Show. The characters are odd, maybe even uncomfortable, but not menacing (at least if you give them the chance).

“I always see them as funny. It’s not [Francis] Bacon,” he said. “I want people to relate to them because I feel like them all the time.”

It’s remarkable how much truer this conception of the work feels after actually meeting Alessi. In a vacuum, it’s easy to imagine many of his scenes being conjured by some unsmiling, egomaniacal goth in a subterranean lair. But while Alessi is serious about his craft, he’s also warm, affable, and down-to-earth—a lot closer on the personality spectrum to Anthony Bourdain than to Aleister Crowley.

It’s no wonder he’s built so many strong relationships in the L.A. scene so quickly. In art and in business, never underestimate the power of being a good hang. The question looming over his New York premiere is how successfully his talents and work can scale in the art world’s capital.

Adam Alessi, installation view of “The Village,” C L E A R I N G, New York, 2023.

© JSP Art Photography

Courtesy of the artist and C L E A R I N G, New York / Brussels / Los Angeles.

HERE IS NOT THERE

Clearing has been deliberately but judiciously using art fairs to tour Alessi’s work around the world for some time. In the past 18 months, the gallery has included one of his paintings—and only one of his paintings—in its presentations at the 2022 editions of Felix, Frieze London, Paris+, and Art Basel Miami Beach, as well as this year’s iterations of Frieze Los Angeles, Art Brussels, Frieze New York, and Art Basel in Basel.

The strategy seems to have paid off. Jack Siebert claimed that buyers across continents “have fallen in love with Adam’s work and will go on wild searches to find the right painting for their collection.” These fans include “collectors from L.A. to Italy who have acquired Adam’s work on the secondary market.” Another plugged-in source told me that a strong contingent of buyers in East Asia have been circling the work via Los Angeles-based intermediaries.

Naturally, the demand has shifted Alessi’s primary market. Most of the large paintings in “The Village” are priced from $40,000 to $60,000; small canvases range from $9,000 to $15,000; and the drawings on view near the gallery’s entrance are asking $4,500 each.

For comparison, Babin said that the small painting he bought at Felix in 2021 cost $2,000. In Alessi’s first solo exhibition at Smart Objects that year, the largest canvas (which clocked in at six feet by five feet) was priced at $7,000; in his 2022 solo outing there, a three-foot-by-four-foot painting was available for $13,000.

While those numbers certainly indicate a significant increase, the operative question is whether it’s an unsustainable or unreasonable one. “The Village” is Alessi’s fourth one-person show. Meanwhile, sources relayed last fall that Gagosian was offering new paintings by Anna Weyant, born nearly two years earlier than Alessi and sporting only one more solo gallery show on her C.V., for between $300,000 and $600,000 each. Several other ultra-contemporary artists with similar track records land on a continuum between his current prices and hers, reinforcing that “too expensive” is always a relative designation.

Some of this ballooning has nothing to do with the art market specifically. Inflation and higher interest rates have come for everyone and everything in the aftermath of the pandemic, whether we’re talking about the cost of paint and stretcher bars, packing and shipping services, or art fair booths and gallery dinners. The mechanism to offset those cost increases is the same for dealers as for landlords, supermarket chains, and multinational corporations: raise prices.

Yet it would be naïve to behave as if the economic aftermath of Covid is the lone driver of this change. The line separating aggression from pragmatism in the gallery sector was being continuously redrawn well before the pandemic, and it’s possible that no Federal Reserve policy or macroeconomic statistic will ever return it to where it used to be a decade or two ago.

“When I arrived in New York almost 15 years ago, there were completely different price brackets for young artists,” Babin said. “Now it’s not easy to find a good work of art under $10,000. So, sadly, a lot of interesting people are getting priced out.”

Adam Alessi, Nervousness (2023). © JSP Art Photography, courtesy of the artist and C L E A R I N G, New York / Brussels / Los Angeles.

Artists, not just sellers, have had to adapt, too. Alessi shrugged off the possibility that chatter about his burgeoning career arc might distract him from his single-minded focus on the work. “I find joy in making, in being at home, in spending time with my family and friends. Seeing this [show] with them is what makes me happy,” he told me. While his sentiment felt sincere, it’s important to recognize that his sober perspective might come from the exact opposite of innocence about art-world machinations.

“Young artists are really no longer naive at all,” Babin said. “Now it’s really part of their DNA to be hyper-aware of the traps and the perks, the do’s and the don’ts.”

In his mind, then, Clearing’s main tasks are to amplify Alessi’s instincts and advise him wherever he needs or wants input, be it on logistics, production, or just the importance of always putting the work first. More than anything, that means positioning him to play the long game: to place his works in the best private collections, make inroads with esteemed institutions, partner with galleries who share Clearing’s vision, and protect him from speculators.

There is alternately work to be done and proof of concept on these fronts. Alessi has yet to be curated into an institutional show as of publication time. But apart from a contribution to a recent White Columns benefit auction, no piece of his has appeared under the hammer yet, either. These basic facts underscore his broader place in the industry on the occasion of his first major New York gallery show: suspended on the high wire between lasting curatorial recognition and quick-twitch market opportunism, doing everything he can to stay steady.

What matters in the end is whether the timelessness and placelessness that Alessi has been pursuing in his images resonates beyond this unsettled moment and his existing base of supporters.

If the motley crew manifested in Alessi’s canvases can mesmerize higher and higher caliber collectors, museum professionals, and other tastemakers in a widening circle of geographical influence, then his success will further prove that a general art-market correction can border on inconsequential to the right individual artists with the right backing. If not, then skeptics can hoist up age-old arguments about the dangers of pushing young talent too far, too fast, even in an epoch where norms seem to be disintegrating daily.

Either way, Alessi’s skewed harlequins and scribbled apparitions will be watching from the forests and color fields, silently hoping behind their curled lips that they’re on the right side of the punchline.

More Trending Stories:

The Art Angle Podcast: James Murdoch on His Vision for Art Basel and the Future of Culture

A Sculpture Depicting King Tut as a Black Man Is Sparking International Outrage