Every week, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, pulling back the curtain…

Ghost in the Machine

If you hoped that the all-consuming, ever-intensifying nature of the artificial intelligence discourse meant that people would soon start asking more of the right questions about the technology’s origins and impact, the latest conversation-starting synergy between A.I. and the cultural sector says otherwise. This time, the machine-influenced work in question came from the realm of pop music. But the controversy could map just as easily onto the art world, and it’s only by excavating its source that we can avoid making the same mistakes whenever a similar moment arrives in this field.

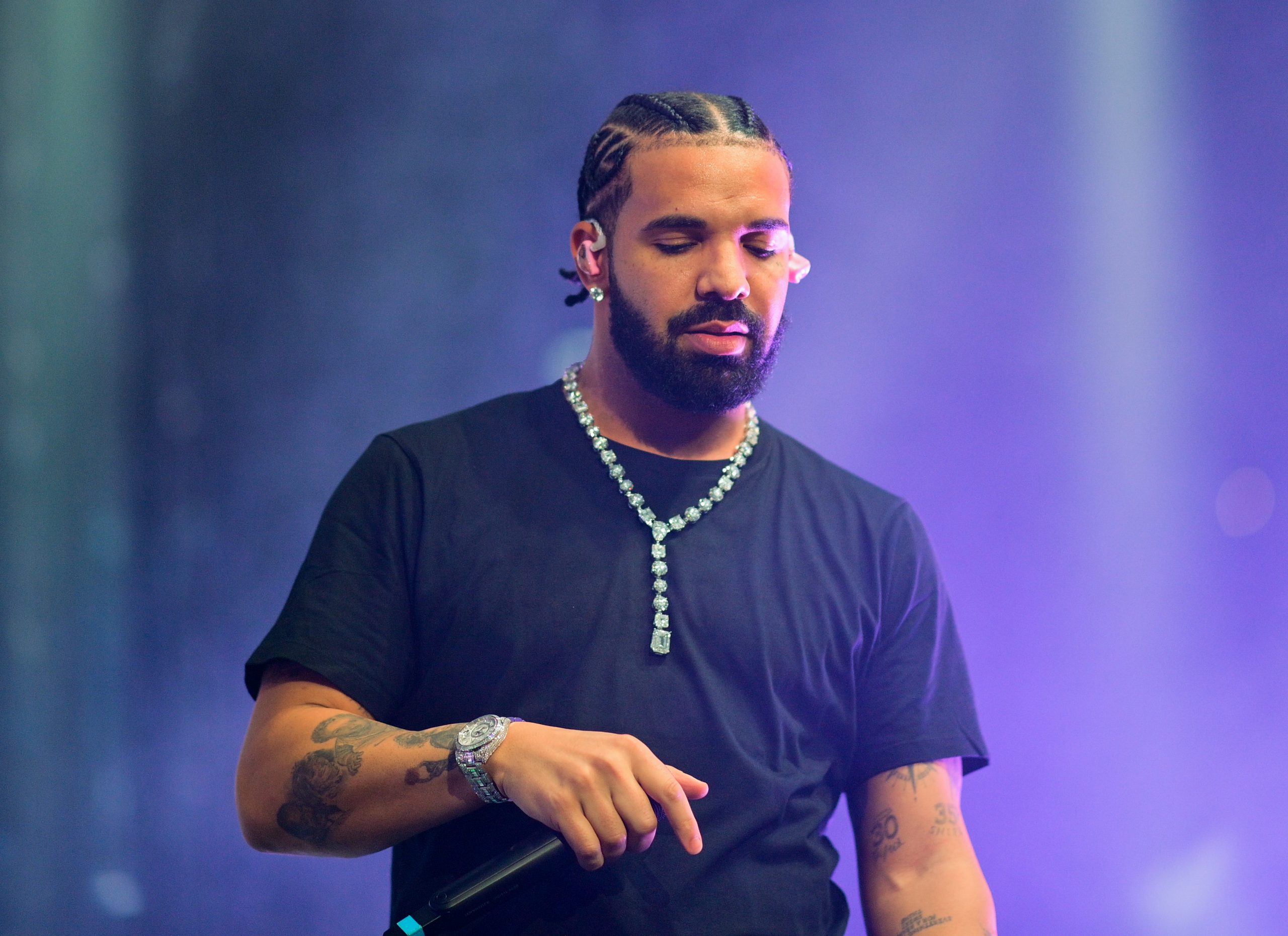

Two weekends ago, a song titled Heart on My Sleeve started running up gaudy listening and viewing numbers online. The novelty was its supposed use of A.I. to generate a faux collaboration between Canadian megastars Drake and the Weeknd. The song’s shadowy creator (or at least, poster), whose TikTok handle is @ghostwriter977, seems to have chosen not to engage with requests for more details from a phalanx of journalists at the most prominent music publications around.

Universal Music Group (UMG), the record label that counts both Drake and the Weeknd among its artists, managed to use intellectual property claims (and its sheer heft) to scrub Heart on My Sleeve from major streaming services within 48 hours of its appearance online. That hasn’t stopped the song from re-spawning through an endless parade of alternate accounts in the days since, as tends to happen in the eternal clash between virality and legal complications. (Any link I could have included in this column would have been dead by publication time, but finding a live one on YouTube is child’s play.)

In a statement released shortly after its initial takedown requests were granted, UMG issued a call to arms to the industry at large, asking “which side of history all stakeholders in the music ecosystem want to be on: the side of artists, fans, and human creative expression, or on the side of deep fakes, fraud, and denying artists their due compensation.”

The irony here is so thick that it couldn’t travel up the average drinking straw. The history of recorded music has no shortage of examples where major labels like UMG did an awful lot of “denying artists their due compensation” via predatory contracts, lopsided legal maneuvering, and more recently, equity investments in Spotify and other streamers, the bane of working musicians across genres.

But the irony runs deeper than exploitation or the shifting boundaries of copyright in the age of A.I. (which is fodder for another column). The business of major labels is, and has always been, releasing hits. Historically, the only ways to do that land on a spectrum that stretches between, at one end, being the beneficiary of good fortune—usually, by signing an artist whose work resonates for reasons that no one could reasonably have anticipated—and, on the other end, trying extremely hard to harness the precise sounds and themes that are bubbling up to the volcano mouth of the zeitgeist in time to capitalize.

How is this done? Broadly speaking, it’s a matter of trying to distill a huge amount of cultural inputs into a discrete set of signals that can then guide the creation, promotion, and/or outright manufacture of songs with the best possible chance of becoming popular. Another way to say it: It’s a massive data-mining operation aimed toward answering the question, “If it seems like X and Y are what people most want now, then we should produce and promote Z to satisfy them.” It is, in short, an algorithm—certainly a less data-scientific one than those used by, say, OpenAI, but an algorithm nonetheless.

Flora Yukhnovich, Moi aussi je déborde (2017). Courtesy of Phillips.

This is as true in the art business as in the music, film, or publishing business. Think back through all the new quasi-Surrealism, figuration by artists of African and diasporic heritage, and reinterpretations of European Old Masters that we’ve seen at art fairs, auctions, and gallery shows since 2016. Aside from a few true visionaries, most sellers make a living by functioning as their own pattern-recognition software.

Music writer and editor Jeff Weiss recently invoked this reality in an exegesis of reclusive superstar Frank Ocean’s meandering, troubled headlining performance during the first weekend of Coachella, the annual Southern California music mega-festival that, perhaps not coincidentally, happened to be going on when Heart on My Sleeve hit the internet. As the alleged A.I. product began ricocheting through the festival crowds impatiently waiting for Ocean to begin his set, Weiss contextualized its origins vis-a-vis the previous evening’s headliner, K-Pop girl group Blackpink, which he portrayed as an algorithmic product of a different type:

On Saturday night, Blackpink came as close as anyone will to answering the following question: What if the Spice Girls had been spawned in the mid-2010s by a vertically integrated consulting firm? There is something hypnotically transfixing about them, as if every visual, graphic, dance shimmy, and autocorrected note has been focus-grouped to ensure Maximum Fun. There is not a single original idea, but it is an immaculate synthesis. They can precisely match the sum of all previous human creativity but cannot provide a note more.

For the uninitiated, Blackpink was formed by the Korean talent agency, record label, production company, and promotional giant YG Entertainment. The firm’s current and past clients include boy-band sensation Big Bang; former Big Bang star (and major art collector) T.O.P, who lit out on a solo career; and Gangnam Style originator Psy, among others. Its success can also be traced back in no small part to a decades-long campaign by Korea’s government and largest business conglomerates to turn K-Pop into the country’s greatest export. (The same actors have also been working to ensure that other branches of Korean culture, including its visual art, follow the same trajectory.) No surprise, then, that Weiss goes on to suggest that Blackpink is less a group than a fusion of vocal, sonic, and aesthetic derivatives optimized for global pop culture’s early aughts revival:

It is easy to cast Blackpink as merely the latest teen pop sensation, which, to be fair, is true. But in an age of rigorous analytics and unseen calculating formulas that feed on what is mostly highly packaged and processed, it’s hard not to see them as one of the first acts of a new era. This is as good as the A.I. will get, and that, in and of itself, is terrifying.

I agree with Weiss about the technology’s likely ceiling, as well as its identity as a digital evolution of human tastemakers in every artistic medium who have collectively spent centuries trying to channel sentiment (and more recently, hard data) into actionable clues in their hunt for the next big artist.

However, I part ways with him on his note of panic, and a closer look at Heart on My Sleeve helps explain why.

Japanese virtual singer Hatsune Miku performs on stage during a concert at the Zenith concerthall, in Paris, on January 16, 2020. Photo by CHRISTOPHE ARCHAMBAULT/AFP via Getty Images.

The Missing Ingredient

The New York Times’s coverage of Heart on My Sleeve called out a crucial element AWOL from most of the rest of the discourse: no one but Ghostwriter977 knows how much of the song was actually made using A.I. In the absence of that information, the default belief seems to be “ALL OF IT OMG THE MACHINES ARE TAKING OVER CREATIVITY AAAAAAGGGGHHHH!”

I suspect that’s an exaggeration. More importantly, it’s an exaggeration that tells us something important about audience expectations for algorithmically influenced works—and more importantly, how to manipulate them.

As fate would have it, we now have a long history of musicians, producers, and corporate entities using generative technology as one ingredient in a more complex soup that is still mostly made manually. It dates back to at least 2007, when Japanese innovators and executives created Hatsune Miku, music-making software marketed as a digital “singer in a box.” The software comprised a complete library of Japanese phonemes recorded by Saki Fujita, an actual female voice actor, so that they could be mixed together in any order and adjusted to any pitch and rhythm by anyone with access to the audio package.

But it wasn’t just Hatsune Miku, the sonic library, that caught fire; it was Hatsune Miku, the anthropomorphized character used to promote the software. Miku’s image and likeness were soon licensed out widely, turning a mascot into something more. Starting in 2011, Hatsune Miku has gone on to achieve success in Japan as an actual pop-star avatar that releases complete, official hit songs and stages sold-out phygital (ugh, I’m sorry) concerts. Yet those outcomes owe their existence to the ongoing collaboration of actual songwriters, musicians, visual artists, and promoters who have used the Hatsune Miku persona as something between a known costume and the fulfillment of a digital fantasy.

The lineage of virtual pop stars has gone in more disturbing directions recently, as typified by the August 2022 debacle that was FN Meka. Described by the New York Times as “a virtual ‘robot rapper’ powered partly by artificial intelligence,” FN Meka was signed by Capitol Music Group for about five minutes, released a single song (titled “Florida Water”) under the company’s umbrella, and was then dropped and profusely apologized for amid outcry that the project amounted to a form of “digital blackface.” More offensive than the lowest-common-denominator song was some of the early promotional content for the project, including visuals of FN Meka—a face-tattooed, green-braided, masculine Black android in cyberpunk attire—in a prison cell being thrashed by a cop while saying, “Free me, I won’t snitch.”

Anthony Martini, a cofounder of Factory New, the tech-forward music company that helped create FN Meka, told the website Music Business Worldwide in 2021 that FN Meka merely combined the vocals and performance of an actual human rapper with “lyrical content, chords, melody, tempo, [and] sounds” influenced by recommendations from “a proprietary A.I. technology that analyzes certain popular songs of a certain genre.” Those recommendations were also reviewed by “one of the most diverse teams you can get,” as Martini later told the Times. This is why he went on to argue that FN Meka was “not this malicious plan of white executives. It’s literally no different from managing a human artist, except that it’s digital.”

The details behind these (would-be) “virtual” pop stars drive home the nuance too often elided by the excitement around new technology, particularly A.I. Algorithms can be leveraged in myriad ways, and to wildly varying degrees, to help create different types of creative works. Think about the conceptual and technical gulf between, say, Ian Cheng’s BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (2018–19), a digital creature whose behavior was endlessly updated by custom-built machine-learning software to simulate a living being, and the infamous Pope coat meme, a Midjourney-generated image of Pope Francis wearing a Balenciaga-inspired white puffer jacket whose origin was a guy in Chicago tripping on mushrooms who thought it would be funny. Both could be considered “A.I. works,” but the meaning of the phrase shifts dramatically from one to the next, partly because we know exactly how each was created.

Ian Cheng, BOB (Bag Of Beliefs) (2018-2019), detail. Courtesy of the artist.

Deep Roots to Darkness

If you’re already feeling unsure about the dividing line between artificial intelligence and slightly less advanced forms of trend-spotting in the arts, then you’re ready to hear about the New Yorker piece written last week by virtual-reality-innovator-turned-tech-critic Jaron Lanier. In the provocatively headlined “There Is No A.I.” Lanier adds his voice to the small group of insiders arguing that artificial intelligence has been unduly mythologized—and made more harmful—thanks to Silicon Valley’s efforts to needlessly obscure its origins and functions. In a sense, he writes, many of his fellow techies are distorting the algorithms to dodge (or at least, delay) fundamental questions about responsibility:

A program like OpenAI’s GPT-4, which can write sentences to order, is something like a version of Wikipedia that includes much more data, mashed together using statistics. Programs that create images to order are something like a version of online image search, but with a system for combining the pictures. In both cases, it’s people who have written the text and furnished the images. The new programs mash up work done by human minds. What’s innovative is that the mashup process has become guided and constrained, so that the results are usable and often striking. This is a significant achievement and worth celebrating—but it can be thought of as illuminating previously hidden concordances between human creations, rather than as the invention of a new mind.

Yet the invention of a new mind is precisely what most of the people behind developing and marketing A.I. suggest that they’ve achieved. Each complex algorithm is dubbed a “black box” whose inner workings are inexplicable even to the people who engineered it, we’re told. Which is convenient, because the spookier and more arcane the rest of us understand the technology to be, the harder it becomes for us to ask how it can be thoughtfully managed, whose labor it derives from, and how those people should be compensated—questions that have higher stakes for artists of all types, from painters and authors to musicians and filmmakers, than to almost anyone else.

(Incidentally, Lanier points out that this is not a new roadblock. Instead, it’s the reappearance of one that has been in place since the early internet, a project that “always felt to [him] that we wanted… to be more mysterious than it needed to be.”)

Writer, computer scientist, and virtual-reality pioneer Jaron Lanier, speaks about his book Who Owns the Future? at the Frankfurt Book Fair in 2014. Photo by Horacio Villalobos/Corbis via Getty Images.

Where does this leave us? Well, whether it’s applied to art or to anything else, what’s called artificial intelligence is, at this point, still probably only a supercharged digital version of what humans have been doing forever, analyzing data in search of patterns that can be used to try to satisfy prompts or answer questions. But we don’t really know its limits, in large part because the technology’s stakeholders are going out of their way to keep it shadowy for the sake of self-interest. And a portion of this self-interest is likely borne out of an age-old realization about the strong causal relationship between mystery and wonder.

To me, this last point is doubly important in the context of art and culture. Many, if not most, people engage with art to be caught up, swept away, or amazed by something they haven’t quite experienced before. As technology gets better and better, it becomes easier and easier for more people to produce more and more artworks that surpass a baseline of technical skill or visual/musical/literary fidelity that would have merited attention in an earlier, simpler, scarcer age. But the growing stampede of good-enough or novelty-first artworks, in turn, creates a numbing effect on cultural consumers; the more you’re bombarded with, the harder it is to be genuinely amazed, especially if every artist or collective or company is transparent (and probably even effusive) about what, exactly, they’re up to.

Generative algorithms are a double-edged sword in this arena. They ensure that anyone can analyze and remix existing works in any medium—a task that used to demand at least enough time, effort, and skill to convince most people to think twice about trying. This shift could mark an inflection point in how we collectively value middlebrow variations on A-level works. In other words, maybe it’s now becoming so easy to do this stuff with shared digital tools that we won’t even give the type of passing, begrudging attention to mediocre executions of voguish concepts or styles that we used to.

Yet, as the Heart on My Sleeve uproar suggests, certain savvy makers might still be able to hype up their own algorithmically influenced works by obscuring how much “A.I.” is really doing (or not doing) behind the scenes. The darker the shroud they can wrap around their works’ production, the more dazzled a still mostly-naive public is likely to be by the surface layer. As in a good psychological thriller, our minds will fill in the blanks with something much more powerful than anything the author could supply.

Not all uses of A.I. are created equal. In some cases, artists may indeed use the technology to push artwork headlong into unknown territory. In others, they may just use it to lightly advance what could be achieved through less sexy avenues. The key, however, is that there is no more proven way for artists to distort our perceptions of which category their work falls into—and thus how important it might be—than to withhold the details. Nothing grows better in darkness than hype.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: don’t even trust first anymore, just verify.