Every Wednesday morning, Artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, a new milestone in the art-tech market prompts a look back into history…

CULTURE CLASH?

Last Wednesday, Sotheby’s auctioned an NFT of the original source code for the world wide web for a premium-inclusive $5.4 million, making it one of the priciest non-fungible tokens ever traded publicly. The sale, as well as the media’s coverage of it, seems to accentuate a philosophical tug-of-war sparked at the inception of NFTs. But a closer look reveals that the conflict is more nuanced than meets the eye—and its finer details capture an important paradox that will determine the trajectory of the crypto-art market.

Offered directly by Sir Tim Berners-Lee, the man generally credited as the primary inventor of the web, the single-lot sale packaged together four elements all blessed by his digital signature. Sotheby’s described them as “the original time-stamped files containing the source code written by Sir Tim; an animated visualization of the code; a letter written by Sir Tim reflecting on the code and the process of creating it; as well as a digital ‘poster’ of the full code created by Sir Tim from the original files using [the programming language] Python including a graphic of his physical signature.”

Bidding for the lot opened at $1,000 on June 23 and soared over the next seven days. At present, the work is in a virtual tie with U.S. national security whistleblower Edward Snowden’s Stay Free for fifth place on the list of most expensive NFTs to date. All sales proceeds will go to “initiatives that Sir Tim and Lady Berners-Lee support,” according to the auction house.

Still, charity doesn’t entirely expunge the irony of tokenizing the genesis of the world wide web. My colleague Caroline Goldstein plucked the conceptual tension out of the zeitgeist when she began a recap of the sale with what has become one of the most hallowed maxims of the digital age: “‘Information wants to be free’ has long been a mantra of internet culture. Turns out, in the age of NFTs, this may no longer be the case… .”

As so often happens with useful, crowd-pleasing turns of phrase as they careen down the neverending chute of pop-cultural shorthand, the motto has been shaken so far free of its origin that we’ve lost the larger, more complicated truth it was a part of. This isn’t just a minor inconvenience; there’s a real argument that it has warped observers’ understanding of the limits of both the NFT market and the tech industry overall.

The autographed poster by Sir Tim Berners-Lee, auctioned as part of the NFT sale. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

“TWO FIGHTING AGAINST EACH OTHER”

The backstory of the slogan “information wants to be free” is a slightly corkscrewed one. Fortunately, Steven Levy, a veteran tech journalist now serving as editor-at-large for WIRED, wrote a brief history of the mantra a few years ago. His retelling is especially valuable given that Levy was its original chronicler (at least as far as the wider world was concerned).

In 1984, Levy published his now-classic first book, Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution. In it he outlined a so-called Hacker Ethic, which he describes as “the list of unspoken principles shared by” the programmers and developers that were then building what they hoped would be a benevolent new world of technology. (As Levy notes, the subjects of his book saw “hacker” as an honorable term already being bastardized by the media to indicate only a villainous subgroup of the tech-fluent—a disconnect we’re still living with some 40 years later.)

Among the tenets Levy codified in his Hacker Ethic was: “All information should be free.” This concept formed the basis of a panel discussion he moderated at the inaugural Hackers Conference, a forum held just outside of San Francisco inspired by, and synced to, the release of his book. It was during this panel that Apple cofounder Steve Wozniak argued that any time a tech company decided not to release a product developed by one of its engineers because of a perceived lack of market, that engineer should be granted full control of their creation to distribute however they saw fit.

Stewart Brand, the Bay Area writer and technologist most responsible for the slogan “information wants to be free,” with a model of the Stonehenge-sized, solar-powered, 10,000-year clock he was working on in 1999. (Photo By LIZ HAFALIA/The San Francisco Chronicle via Getty Images)

Enter Stewart Brand, the Bay Area counterculture mainstay who compiled the landmark Whole Earth Catalog and co-organized the Hackers Conference. In response to Wozniak, Brand had this to say:

On the one hand information wants to be expensive, because it’s so valuable. The right information in the right place just changes your life. On the other hand, information wants to be free, because the cost of getting it out is getting lower and lower all of the time. So you have these two fighting against each other.

(You can read the full exchange in Brand’s edited highlights of the conference here, on page 49. Or if you have a Getty Images subscription, you can watch a short clip of it here.)

Why has public memory largely forgotten the first half of Brand’s insight? I suspect the answer is a brew of populist appeal and Silicon Valley marketing. As a writer whose work recently went behind a paywall, I feel pretty comfortable saying that most people now believe they should have the opportunity to learn whatever they want to know online at no cost.

Beyond journalism, open access also links up to the ideal, often unrealized, of transparency as a pillar of both liberal democracy and the free market. Sure, the thinking goes, you should have to pay for some things. But you should be allowed to sample them for nothing first or have access to, say, an ad-supported version gratis. At the very least, users tend to unite around the belief that they should be able to get a clear understanding of what’s on offer across the market before shelling out for any given product or service. “Information wants to be free” plugs right into this prevailing sentiment.

Big Tech has also been passionate about seeding this idea throughout the culture because it’s been indispensable to their business model since the mid-2000s. Facebook, Google, Amazon, and other Silicon Valley behemoths have generated hundreds of billions of dollars in revenue by offering “free” services that covertly monetize your personal info in the process.

It’s a dynamic that undergirds two other popular but disquieting tech adages from the past 15 to 20 years: “The best minds of my generation are thinking about how to get people to click ads”; and “If you’re not paying for the product, you are the product.” If you were managing the image of one of the Goliaths inspiring these quips, wouldn’t you too be working hard to rally the public around “information wants to be free” instead?

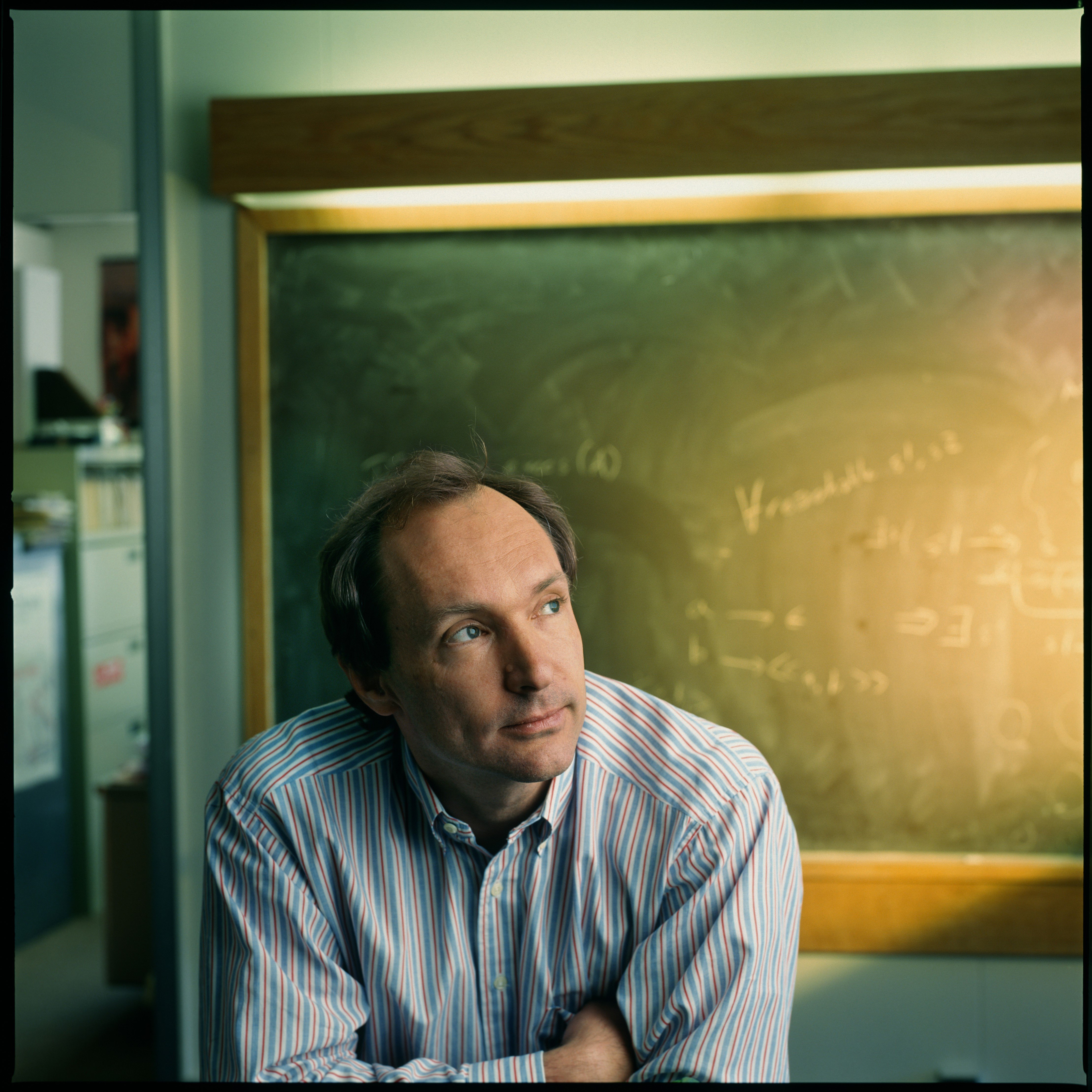

Tim Berners-Lee, physicist, computer scientist, inventor of HTML (Hypertext Markup Language) and founder of the World Wide Web, speaks at the Digital X conference in 2021. Photo by Oliver Berg/picture alliance via Getty Images.

HERESY OR RED HERRING?

This leads us back to the $5.4 million paid for Berners-Lee’s NFT. The sale is a perfect embodiment of the opposing forces Brand identified in his comment at the Hacker Conference nearly four decades ago. Despite its ills and shortcomings, the web has no rivals when it comes to liberating information for no-cost consumption at scale. Yet marketing its plumbing as a unique digital asset also typifies how badly information “wants to be expensive” when deployed in the right moment to the right people.

This internal strife has been visible in the art-tech community since NFTs debuted. Several artists, dealers, and thinkers deeply invested in the progressive possibilities of technology have described non-fungible tokens as something close to heretical. To this group, a core appeal of born-digital, networked artworks is that they can operate outside the rules of scarcity-driven cultural capitalism. Why lean into a technology that just reasserts the same exploitative, away-from-the-keyboard logic in a world designed to be free of it?

Case in point: Anil Dash, who co-invented NFTs with the artist Kevin McCoy, stressed in an Atlantic op-ed earlier this year that the duo originally dubbed non-fungible tokens “monegraphs”—a mashup of the phrase “monetized graphics”—in part as a tongue-in-cheek joke. When the duo debuted their innovation at Rhizome’s Seven on Seven conference in 2014, Dash wrote, the name “prompted knowing laughter from an audience wary of corporate-sounding intrusions into the creative arts.”

So isn’t it a little rich (in both senses of the word) for Berners-Lee to enable a seven-figure auction for an artifact of the web, which he characterized in a statement released before the sale as a resource whose “knowledge and potential” he “sincerely hope[s]” will “remain open and available to us all” in the future?

Maybe not. There’s another sense in which the culture-clash narrative is just as much of an oversimplification as lopping off Brand’s statement about how information wants to be expensive. NFTs are an imperfect solution to many of the worst problems facing artists in the traditional market. Still, they don’t block proponents of alternative economic strategies (if not full-on anti-capitalism) from pursuing their goals.

Kevin McCoy, Quantum (2014). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Call me a cynic, but I don’t think that either the crypto-whales or the few traditional collectors backing up the Brinks truck for high-priced NFTs would have channeled their money into advancing progressive digital art systems had blockchain not reintroduced scarcity and exclusivity into the market for new media. Believing that would be a little like believing that plutocrats would have diverted their regal dining budgets into stamping out world hunger if only Andre and Edouard Michelin had never started slapping star ratings on their favorite restaurants. (Fun fact: Turns out their whole system was a ploy to sell more tires. It’s that Michelin family.)

Yes, so far only a shallow pool of top artists seems to be attracting the vast majority of cash spent on NFTs. Yes, some of the biggest money-makers have been souvenirs of meme culture rather than boundary-pushing, conceptually challenging artworks. Yes, the ecological damage being caused by the Ethereum blockchain (where most of the NFT trade lives) is a major concern.

But there are at least some artists who have prospered (or at least stabilized their studios) thanks to non-fungible tokens, to say nothing of the greater good some of this nascent sustainability has generated. For instance, it’s hard for me to completely dismiss NFTs as a force for good when a trans teen artist says of their work in the milieu, “I genuinely think it saved my life.” More artists, particularly those from traditionally under-recognized demographics, should get more opportunities as resources continue to flood into NFTs, and attention on the technological vulnerabilities and market inequities should (hopefully) prompt thoughtful problem-solving.

From this perspective, Berners-Lee’s $5.4 million NFT is less a monument to art-tech irony than to a paradox of crypto: its shortcomings and its potential can both be real at the same time. As with the web itself, which of those two sides will win out is a question it may take generations to find out for certain.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time remember: What most of us know (or think we know) is almost always just a fraction of the whole story.