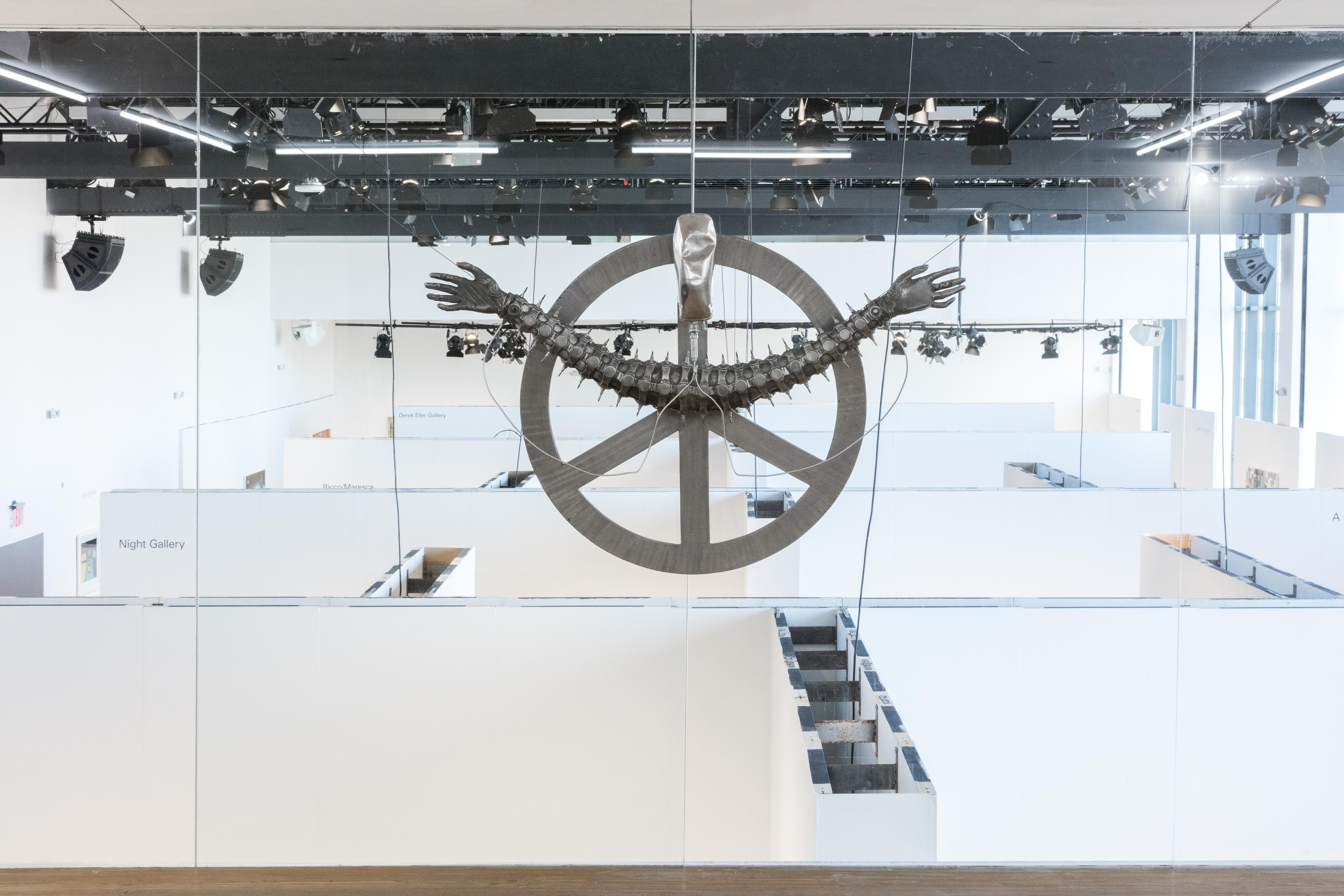

The aliens have landed at the Independent fair in New York—or at least, the work of science fiction legend H.R. Giger has. On the booth of New York gallery Lomex, looming above the galleries like some otherworldly crucifix, a pair of outstretched extraterrestrial arms and an ominous bag of blood are nailed to a giant peace sign.

The aluminum sculpture is the centerpiece of a presentation curated by the gallery’s founder Alexander Shulan, with artists Oto Gillen and Valerie Keane. The artists selected works of their own to be shown in dialogue with a selection of pieces by Giger, best known for his work in films like Ridley Scott’s Alien.

Giger, who died in 2014, is hardly a fixture of the art world circuit. But Shulan, who now works with the Swiss artist’s estate, believes that that time has come for the art world to recognize Giger’s contributions not only to pop culture, but to contemporary art.

“It’s insane to me that Giger hasn’t had the appreciation in the art world that he deserves—in mass culture he is a household name,” Shulan told Artnet News. “Giger created the aesthetics of science fiction undoubtedly, but his experimentation in creating a paranoia around technology was also hugely influential.”

H.R. Giger’s Aluminum Floorplate with Biomechanoid

Matrix (1991), shown alongside a sculpture by Valerie Keane (right) at Independent, New York. Photo courtesy of Lomex, New York.

And that influence, Shulan believes, extends to the art world: “I won’t name them, but I can think of tons of contemporary artists who are aping Giger’s aesthetic.”

Even without the art world recognition, for the wider public, Giger remains hugely popular. Lomex’s recent exhibition of the artist’s work, co-curated by Shulan and Alessio Ascari, was the six-year-old gallery’s most-visited show of all time.

“We had easily between 500 and 1,000 people at gallery a day. It became a phenomena,” Shulan said.

Work by Oto Gillen and Valerie Keane at Independent, New York. Photo courtesy of Lomex, New York.

The gallery doesn’t have any other projects with the Giger estate currently in the works, but there are European museum shows in the pipeline. (An outing with a U.S. institution is Shulan’s long-term dream.)

For the Independent fair, Shulan, Gillen, and Keane aimed to create a presentation that spoke to Giger’s dystopian vision. They pairing prints and sculptures by the artist with a giant, high resolution photograph on aluminum by Gillen—a long-exposure shot of illuminated signage reflecting in a pool beneath a New York City skyscraper—and intricate hanging sculptures of acrylic, stainless steel, and aluminum by Keane.

But the star is undoubtedly the alien peace sign sculpture Leben erhalten (Life Support), a 1993 work on loan from Giger’s museum in Switzerland, and available for purchase, price on request.

H.R. Giger, Leben erhalten (Life Support), 1993, with a sculpture by Valerie Keane at Independent, New York. Photo courtesy of Lomex, New York.

The work, which is inspired by the peace sign’s origins as an anti-nuclear war symbol, was Giger’s way of speaking to the anxieties of the Cold War. It was used as the cover art for death metal band Carcass’s 1993 album Heartwork.

“Thousands of people have tattoos of this,” Shulan said.

“It’s interesting to have this in art world context,” he added. “The art world has a hard time understanding adjacent subcultures. That’s a fault of the art world. Giger became so entrenched in a subcultural aesthetic, and those images were so widely distributed in mass culture, that the art world ignored them.”