Inaugurating the Pace Gallery‘s new permanent space in Palo Alto, James Turrell presents a range of works, including Pelée (2014), a site-specific installation which uses a wall of LED tiles that slowly change color on a two-and-a-half hour loop, as well as seven of his Reflective Holograms.

Speaking to artnet News on the phone between installation commitments, the artist explained that the show at Pace’s small 3,200 square-foot gallery includes a selection of “collector friendly” works designed to introduce the southern Bay Area’s tech-centric audience to fine art. The exhibition is part of the revitalization of the entire Bay Area’s art scene, which is undergoing rapid growth.

As Pace Palo Alto’s president Elizabeth Sullivan notes, Turrell is the ideal choice to inaugurate the space due to his “formidable practice and tireless commitment to exploring technological possibilities,” factors that sit will with Palo Alto’s tech-wealthy collectors.

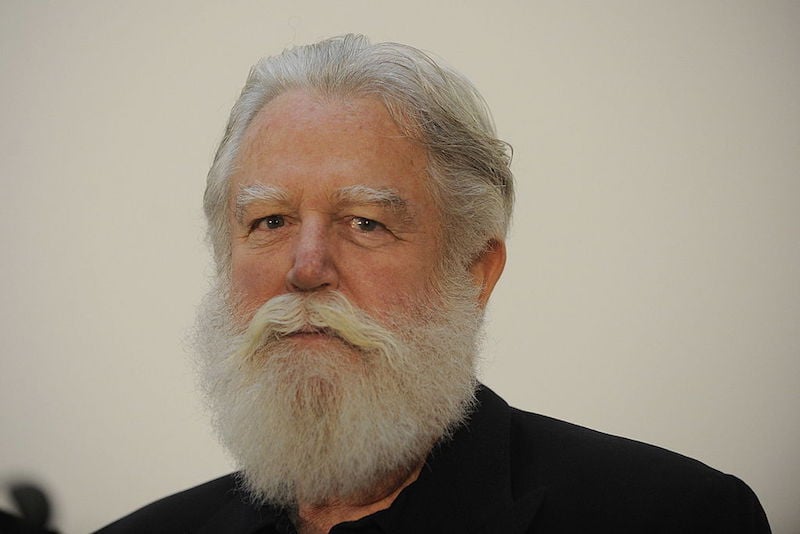

An early proponent of conceptual art, Turrell spent his entire career championing the use of light as an artistic medium. With a varied academic background including degrees in art, perceptual psychology and mathematics, his work is characterized by grand ambition and focuses on color, light, perception, and space.

Turrell spoke thoughtfully on a range of issues from physics to the history of art—and offered one or two surprising anecdotes below.

James Turrell Pelée (2014). Courtesy of Florian Holzherr © James Turrell, courtesy Pace Gallery.

How did your studies and degrees in art, perceptual psychology, and mathematics inform your work?

Well, the main thing is that when you have a class in art you’re trained in the color wheel, so if you take blue paint and mix it with yellow paint, you get green. If you mix blue light and yellow light you get white, so I had to learn the spectrum. The other thing is that I had to learn how we perceive, so I took a different course or direction by virtue of my interest in light.

You can’t hit the moon with Euclidean geometry, so you have to learn that space is curved, you have to learn line geometry, and you have to have whole different things to grasp. We’re beginning to learn the spectrum, but in general people still refer to the color wheel. It did inform the beginnings quite a bit.

James Turrell Pelée (2014). Courtesy of Florian Holzherr © James Turrell, courtesy Pace Gallery.

How has your practice changed since then?

It adapts to how I work, and in some way I’ve adapted and used art to do the kind of projects I’ve wanted to do, which are more like the crater, or the pyramid in Yucatán—larger projects. But in the end you deal with what art is and you adapt.

To what extent does the use of technology define your work?

I think I had to wait for technology to catch up just to mix light. Tungsten was a light that you could change, but it was unrealistic in terms of cost. I previously mixed neon light and it was very cumbersome. I thought that if we can go to the Moon, we can mix light, but it took a long time to actually happen. So at least I had the great advantage having seen technology catch up with my ideas.

You can go to Moscow and look at the solar organ that Alexander Scriabin used and had his wife play to his compositions, and you can see how far things have come and how far they’ve progressed. And also Thomas Wilfred had the Clavilux color organ, his was an improvement over Scriabin’s but nonetheless also crude. These things have improved and have changed; you can now mix two lights, although it’s taken a while for us to have that ability.

If you’re a painter you don’t have to be an alchemist like you had to be in the Middle Ages to get your colors. You can go and buy thousands of colors already mixed, but that’s not true with light. So I’ve had to be involved in how it was made and sometimes even make the instrument before I can use light to perform what I’d like.

James Turrell Pelée (2014). Courtesy of Florian Holzherr © James Turrell, courtesy Pace Gallery.

What was the reaction to your early Light Projection work from the 1960s?

At that time the response was interpreted as a political thing against material. You could still own it, so I didn’t find it to be that, but that was sometimes how it was taken—that I was making something that was immaterial, and it went along with performance art and things of that sort.

Being immaterial and being a political statement wasn’t really there on my part, but it would seem that way at one time. I had a number of reviews that commented on that, but that’s all long ago.

Why do you choose to work with such a challenging and intangible material like light?

It has the same potential as sound has. Abstract sound is able to work with emotion more directly because you don’t have it connected to an involved source so much. Just as people made symphonies or devised instruments to make sounds, I’m interested in making the instruments and the things that produce light and can get directly to that.

It’s a little bit like looking into the fire… You can kind of drift away in a faded state which is not not thinking, but it’s definitely not thinking in words. So if you want to work with that kind of trigger to emotive feeling, you have to work with it in that pure state, that’s why light was so powerful, it was something that we as a small children are attracted to. We have this very well known correspondence to light sources and looking at light. It’s very interesting because we’ve had recent evidence now suggesting that light knows when we’re looking, which is almost to imbue it with consciousness. But that’s anthropomorphizing, so that’s another subject.

James Turrell Untitled (XIX L) (2007). Courtesy of Florian Holzherr © James Turrell, courtesy Pace Gallery.

What influenced you to arrive at your practice?

If you look at the history of art you’re often going to look at a great deal of depictions of light, and so this is nothing new, I mean [JMW] Turner certainly depicted light and more recently [Mark] Rothko and Ad Reinhardt, who’s very underrated.

Sound and light are a strong influence on each other and so that was my great interest, and also getting at a form in light when you can really can deal with feeling and emotion without working through symbolic or associative thought. Then of course you have [Johannes] Vermeer, Turner, who was actually very prescient, and there’s Abstract Expressionism and Color Field. And then you had the early experimenters Thomas Wilfred and Scriabin. This was something that was strong for me to see in the history of art, also you have Caspar David Friedrich who really dealt with light and all the Norwegian and Scandinavian painters, and the more emotional light with Goya, and Velazquez and Caravaggio. And, of course, I haven’t yet mentioned the Impressionists, who were preoccupied with the perception of light and looking at it like Georges Seurat did, actually painting what it looked like, how it changes, and how it evolves.

These kind of works were very important, and so what I’m doing is certainly within this mainstream history, it’s just that I didn’t want to depict light, I wanted to use light itself.

You once said “We are part of creating what we think we perceive.” What did you mean by that?

Well there’s a lot of prejudice of perception, and we’re often unaware how we perceive, and so we’re unaware of the fact that we have a strong part in creating that which we behold.

Of course, the Eastern cultures believe that almost everything that happens in front of us is created by us. But we have a more rational Western view, and we like to feel if we are part of creating that in front of us we’d like to know a little more about it.

Certainly that’s true just with color perception, with the Sky Spaces that I have, I don’t actually change the color of the sky, I change the context of vision, which gives a very different color to the sky. And it’s only then that you realize that you’re the one that really makes the color of the sky. This is not something that has a color it’s something that we attribute to it and it’s very easy to see how that can be worked just by changing the context of vision and kind of knowing that, and knowing these anomalies in how we perceive is helpful in realizing how we create the reality within which we live.

James Turrell Untitled (XX E) (2007). Courtesy of Florian Holzherr © James Turrell, courtesy Pace Gallery.

If you could own any artwork from art history, what would it be and why?

A lot of art collecting and art ownership has to do with what we treasure, and I always found that I treasured light. In terms of my ownership I remember one time in the south of France in a museum, I was looking at a Juan Gris [work] and I was holding a briefcase and I thought ‘That painting could fit right into this briefcase.’ Of course, security in those days was nothing.

It’s the one time I have to admit that I had the feeling of wanting to possess [a painting]. But, you know, we do possess them when we see them. And that’s one of the things that’s interesting about art, the actual presence of the work and being in front of it, you do own it. It does get paid for by these people who do the collecting, and if it’s worth enough they generally surrender it to society for tax reasons. So in a way it’s a good thing that these things get carried on.

I’ve traded for art and I’ve sold the art I’ve traded, so I’m not a big collector of art, but we as artists do depend on people on wanting to treasure it and wanting to own it.

“James Turrell” runs from April 28 – July 30, 2016 at Pace in Palo Alto, CA.

This interview has been edited and condensed.