Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons have co-curated “Now,” an exhibition of Koons’s work, all of it from Hirst’s collection, for the Hirst-owned Newport Street Gallery in London. Coming from these pioneers of the contemporary artist-as-CEO phenomenon, twin emperors of personal-brand-building and the generation of art as product, one can’t help but sniff around for a power play. Is this a display of collectorial machismo? A tussle for dominance between two art world silverbacks? An Instagram-worthy display of brush-in-hand bromance?

In a sense, of course, the power play is right there on the surface. Just as, in 2008, Hirst cut out the middlemen in taking his works directly to auction, here he offers a similarly streamlined approach to the institutional retrospective: no bandwagon-jumping curators, no chummy gallery directors, no self-serving advisory board, no pandering to the moral majority, no loans. Just artists, making art, selling art, buying art, and showing art.

Koons’s 2014 retrospective at New York’s Whitney Museum has since toured to the Pompidou in Paris and Guggenheim Bilbao. While he’s exhibited major series in the UK, Koons’s last survey show on these shores was at Anthony d’Offay’s gallery back in 1994. For a gallery pitching itself firmly at a general, domestic audience rather than jaded, motion-sick riders on the international art world carousel, there’s logic to holding a Koons show at Newport Street. Not least because, thanks to coverage of prominent exhibitions elsewhere, much of this is work that is known in the UK but has not been seen.

Physical presence is important to Koons. You need to get up close and admire the perfect matte texture on the giant eggshells in Bowl with Eggs (Pink) (1994-2009), the plasticky sheen on the aluminum “inflatables” so convincing that you can almost smell vinyl. You need to share space with the Balloon Monkey (Blue)(2006-13) to notice how its shine is so high that the edges of its outline blur off into reflective space and it appears to be floating, weightless. The tin-potty cheapness of the stainless steel Italian Woman (1986) firmly imposes itself up close, as does the colour-by numbers contouring of the oil on canvas Boy with Pony (1995-2008). When the surface is the subject, it helps if you can actually see the surface.

Jeff Koons, Play-Doh (1994-2014). Installation view of “Now”, at Newport Street Gallery. Photo: Hettie Judah

“Jeff Koons: Now” shows a selection of the Koons works that Hirst has collected over the last 12 years, including an example from the early vinyl and mirror Inflatable Flowers series (1979), which, unlike the eternally bulging metal “inflatables,” looks saggy around the edges. Themes of inflation and tumescence thread across the lower floor. From the obsolete boxfresh vacuum cleaners of 1980’s The New (a title that seems more ingeniously vainglorious with every passing year) to deadly bronze-cast breathing apparatus, through Balloon Monkey to the artists’ own cock, perky as the Monkey’s tail and shown from two angles (glimpsed lengthwise from the perineum in Ice – Jeff on Top Pulling Out and side on, slick with saliva and ejaculate, in Exaltation, both 1991).

There’s puckering here too: a counterpart to all that blowing and sucking. Placed in adjacent galleries, the wrinkled twists of Balloon Monkey’s joints correspond, uncomfortably, to the crimped starburst around Ilona Staller’s anus in the photo work Ice as she parts her cheeks with long-nailed-hands.

Jeff Koons, Seal Walrus (Chairs) (2003-09). Installation view of “Now”, at Newport Street Gallery. Photo: Hettie Judah

It is in this last room of the ground floor, with the two Made in Heaven pictures and the Bowl with Eggs that one starts to question the absence of a curator. On the one hand that they might act as a kind of artworld prophylactic, a protecting figure insinuated between the artist and post-fellatio-pre-heartbreak images of him with his ex-wife (for just how does one go about disinterestedly curating such images of oneself)? On the other hand, because for no easily identifiable reason, despite the bright colors and festive spatters of spunk beneath Staller’s electric blue mascara, the room feels empty and downcast.

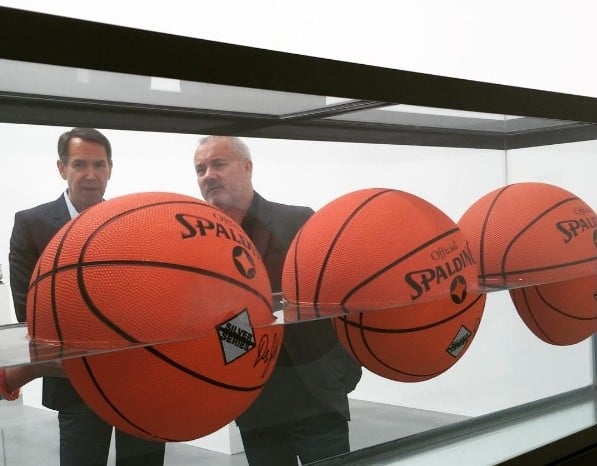

The upper levels, while they do also show wall-based works and a basketball floatation tank, offer a virtuoso overview of Koons’s experiments with cast metal, his subjects becoming more, rather than less, banal over the course of his career. The sentimental art and kitsch reproduced in stainless steel for the mid-1980s Statuary gives way in the second upper gallery to the “inflatable” aquatic bestiary of the Popeye series. The technically brilliant Seal Walrus (Chairs) (2003-9) pushes the illusion to its outer limit—the titular aluminium “inflatables” are shown magically sliced through by a stack of “plastic” chairs. Koons the erotic narcissist from the floor below has turned into Koons the showman, Koons the suburban conjurer, with his merry troupe of maritime acrobats.

Jeff Koons Bowl with Eggs (Pink) (1994-2009). ©Jeff Koons

The last room houses a colossal Play-Doh sculpture, sibling to that in the Whitney show. US critics may have wheeled out psychedelic poop comparisons, but after six rooms of flawlessly executed work, with never the touch of human hand apparent, Play-Doh would seem to betoken anal fixations of a different kind. Infant Jeff does not strike one as the kind of child to have colored outside the lines. To spend twenty years (1994-2014) developing a monument to smushed-together modeling clay colors is far more transgressive than anything so suburban as having smutty photos taken with your wife.

“Jeff Koons: Now” is on view at Newport Street Gallery, London From May 18 – October 16.

To mark the opening of the new exhibition, Newport Street Gallery has launched its new “Summer Lates” opening hours, remaining open until 10pm every Saturday.