Manal Al Dowayan, The Cowboy (2015).

Image: Courtesy Manal Al Dowayan.

A handsome man with deep eyes and full lips squints towards the sun, clad in a cowboy hat and a worn-in college sweater. The portrait is of Manal Al Dowayan’s deceased father, who casts a long shadow over the artist’s current exhibition, “And I, Will I Forget” at Cuadro Fine Art Gallery in Dubai.

The show is the fruit of Al Dowayan’s residency at the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation last year, and features silkscreens derived from a tin box of 600 Kodachrome slides that her father had given her when she was twelve. He had documented his life and surroundings—a farewell in Saudi Arabia as he prepared to leave to study in the US, as well as documentation of mountain hikes, a visit to Spain, and even an image of the artist as a newborn, which, poignantly, ceases the collection of slides.

“Don’t we always relive someone’s memories? Isn’t that what we do when we read stories or view artworks in a museum?” Al Dowayan says in an interview with artnet News.

Manal Al Dowayan, Ties in the Boat on the Lake (2015).

Image: Courtesy Manal Al Dowayan.

Recognized for her photography, installation, sculpture, video and neon work, the Saudi-born artist’s practice is rooted in the themes of memory, archival material and the status of Saudi women today. Her latest body of work once again tackles the subject of memory, but in a rather existentialist manner. Here, she is concerned with the fate of an unknown, untraceable, story-less memory. This comes through in the show’s hanging—there is no chronology or path, per se. It is beautifully hung, and just as haphazardly placed as those of the images in the tin box.

Over the last year, Al Dowayan printed and reprinted her father’s images, which he had shot between 1962-1973. “There’s a personal journey here: my connection to his journey and the global idea of memory and lost memory and what you do with a memory with no story,” she says. “Do you allow yourself to forget? I chose to give it a new life.”

By way of first impressions, there’s a Pop art element to the show. Perhaps Rauschenberg’s practice influenced Al Dowayan via osmosis—she slept in a bedroom stacked with the late graphic artist’s books. In print after print, Al Dowayan studied the images keenly and attempted to piece a puzzle together, but there was none, so she created one. She feels a great sense of suspension in these images. “He was a person floating in this in-between space just like I am,” she says of her father, who passed away from Alzheimer’s in 2010. “It’s a space that you exist in that you can’t describe. It’s sometimes lonely or special and you float between those two states of mind.” Al Dowayan attempts to resurrect and recall her father’s memories and in doing so, offers them new narratives.

The premier artwork of the Al Dowayan patriarch is printed on raw, untreated linen, one of four materials that punctuates the exhibition, but also interrogates the storyline through their very substance: Linen is flat, mirror mirrors, paper is delicate and copper has a sepia effect. Through copper and mirror, the audience becomes reflected in the artwork. Al Dowayan intends this, to build a narrative and ultimately, the story is no longer just her father’s, but becomes a collective memory. Overall, the exhibition confirms that she has been on a quest. She succeeds in transferring that desire; visitors to the gallery circle around the space, trying to build narratives, too.

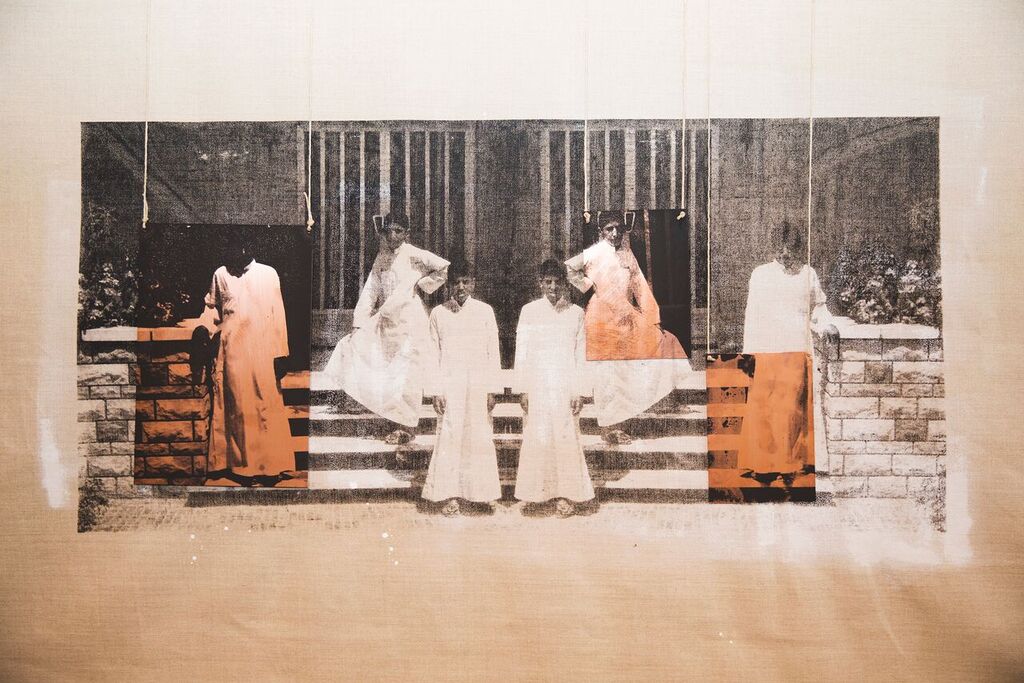

Manal Al Dowayan, The Boys (2015).

Image: Courtesy Manal Al Dowayan.

The materials are also driven by emotions. “Sometimes they reflect darkness, lightness and confusion that a memory goes through,” she says, adding that that is difficult to assess—essentially, it is a grandiose guessing game. Al Dowayan has manipulated imagery in some pictures to offer new narratives: in a copper image of six men on a boat on a lake, for instance, she has attached a linen background with more trees to create a panorama; in another of a car on a dirt road, she dangles two identical portraits of a little girl. This layering is typical of the artist’s practice, where, she says, “I’m preserving someone else’s memories and in turn, preserving me,” she explains. “It’s a human instinct for immortality. We all want to leave something behind.”

All of the artworks hang by a string, except the premier portrait of Al Dowayan’s father. He sits in a memorable spot at the gallery’s entrance, impossible to miss. “There’s a pioneering spirit to this image,” she says. “That spirit has helped me do things.”