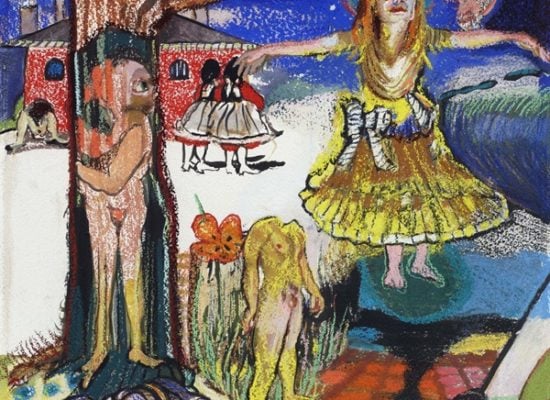

Artist Natalie Frank’s first museum show (and the first show devoted solely to her drawings), opens at the Drawing Center in Soho today (through June 28), and it is already generating serious buzz. Frank is well known for her bold, expressionistic paintings that call to mind the visceral, fleshy portrait work of Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon, and Jenny Saville to name a few. This time around, the subject is one she has immersed herself in for the past several years—the unsanitized versions of the Brothers Grimm fairy tales.

Frank decided to visually tackle the characters and scenes that represent the dark underside of these stories, which were written between 1812 and 1857. She has addressed the lesser known aspects of incest, rape, physical violence, and other taboo themes that were phased out or glossed over as the stories were translated to English starting in the 1820s.

Take, for instance, the tale (actually a single paragraph) titled “The Stubborn Child,” that tells of an ill-behaved boy who “never did what his mother told him.” As a result, the Lord “did not look kindly on him,” and the boy became so ill that “no doctor could cure him.” He eventually dies but after he is buried, “one of his little arms kept popping out.” Observers attempt to cover the arm with fresh earth, but to no avail. The tale comes to a quick close by telling how his mother “had to go to the grave herself and smack the little arm with a switch. After she had done that, the arm withdrew, and then, for the first time, the child had peace beneath the earth.”

Along with the show, Frank’s work has inspired a book, Natalie Frank: Tales of the Brothers Grimm, that will be published by Damiani in May and distributed by D.A.P. in the US and Abrams & Chronicle in Europe. It features essays by professor Jack Zipes, who finished translating the Grimm fairy tales from German last year, as well as feminist art historian Linda Nochlin and theater director Julie Taymor.

The Drawing Center show, which features 25 of the 75 works in Frank’s series (see a selection in the slideshow above), is curated by Claire Gilman. It will travel to the Blanton Museum of Art at the University of Texas, Austin (July 11–November 15).

On April 30, the Brooklyn Museum will host a panel discussion, featuring Gilman and Zipes, that will focus on fairy tales, sexuality and feminism in Frank’s work. The event will also include readings of select Grimm tales by author Michael Cunningham, choreographer Bill T. Jones, and essayist Ariel Levy.

We caught up with Frank on the eve of the show’s opening to talk about the inspiration she found in these dark tales as well as her methodology.

In 2011, when her artist friend Paula Rego suggested that Frank read the tales, she noted that no one had ever really illustrated them. “I started to read through Jack Zipes’ translation and just found the stories so amazing. I just started to read it as literature, not even thinking about drawing. But the visual images just kind of popped out so I started to think about drawings,” said Frank.

The themes in the tales connect with “many of the things I’ve been interested in since I was very young, which is probably why I was drawn to these stories, ” Frank explained. These include issues like “the sexuality and violence that run as an undercurrent to everyday life. And it has a bit of magic and transformation as well. The women in the Grimm fairy tales are very fascinating and very diverse. It’s unlike what I remembered reading from fairy tales.”

Frank says she had never done a cohesive body of drawings. “So I started just sort of casually going through the book and drawing ones the I liked. I was heavily focused on paintings on canvas and panel.”

But when Gilman saw the drawings, she immediately wanted to do a show. Frank says: “I started thinking about doing a book because of obviously the source and the stories that as images just started to aggregate. I thought how nice it would be to kind of see them in that progression, to have them grouped in that way. Some of the figures and characters I was drawing kept repeating. Originally it was just going to be color drawings that were fairy tales but it became something much more.”

It’s not hard to see why Frank sees the drawings in many ways as “paintings on paper. The pastel really sits on top and the gouache sinks in, so it’s kind of a combination of something that’s both decorative but also painterly at the same time.”

Frank hopes viewers get that “humor is also a big thing and an undercurrent” in these works. “Not in a gruesome terrifying way but in a really humorous ‘folly of humanity’ kind of way.”

The Brothers Grimm “are just such complex, funny, beguiling storytellers that I think people will enjoy being introduced to them and getting to know the unsanitized version. I hope there’s more levity in this body of work than in some of my past series of work, and a greater freedom and play with color and imagery and materiality.”

Frank said the experience has made her want to do more drawings inspired by literature. Other literary works she might possibly mine for inspiration are The Story of O and Don Quixote, as well as works by Ovid. “But I think I’d like to do them all with an eye toward women and representations of women and women’s bodies,” she says.