The Newark Museum of Art today sold off a slate of works at Sotheby’s despite considerable objections from experts and scholars. The sell-off generated $5.9 million for the institution.

Of the 11 works on offer at the auction of American art in New York, one was unsold, two sold for under estimate, and the remaining eight exceeded their presale expectations.

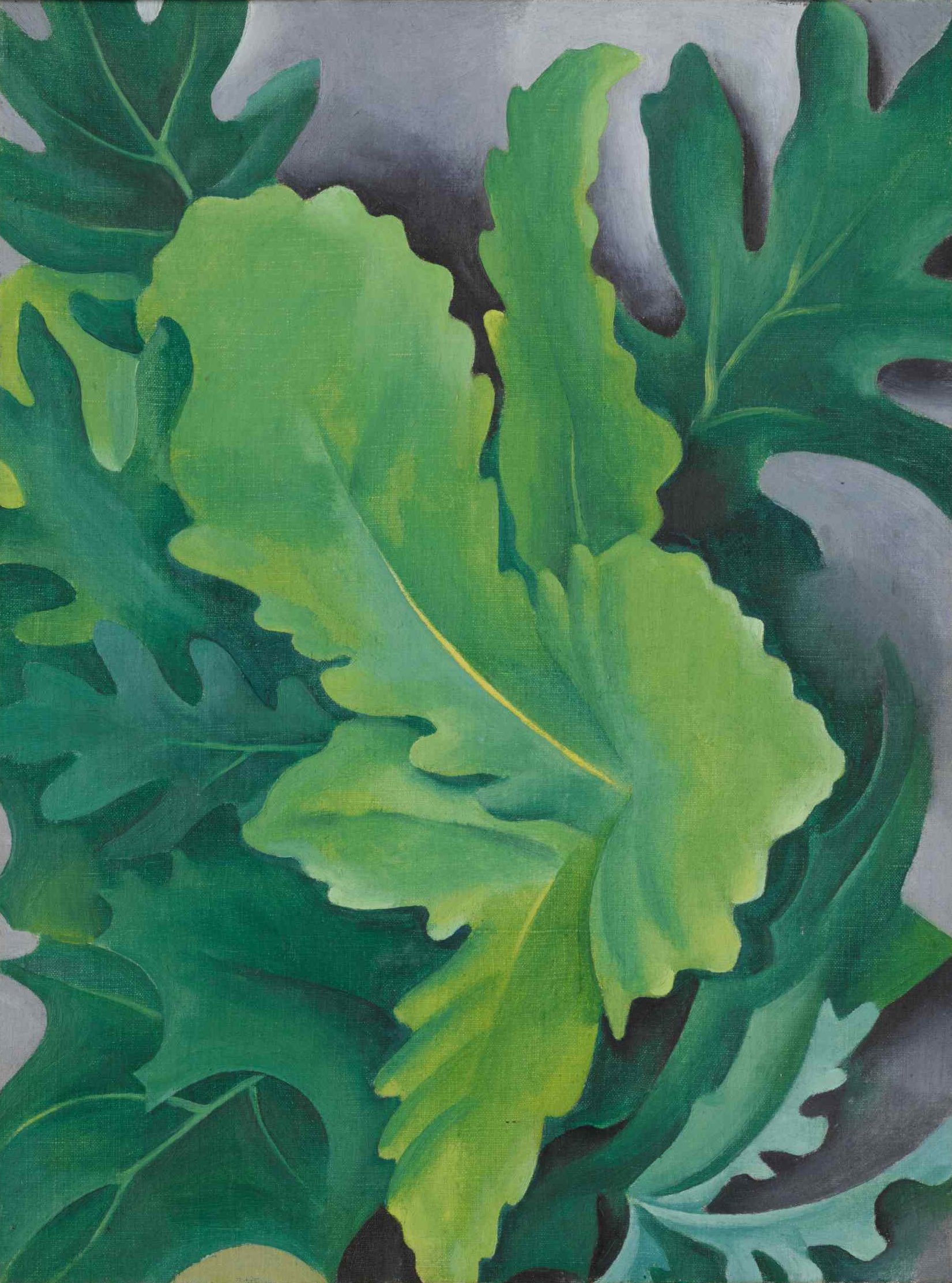

The highest price paid was $1.2 million for Georgia O’Keeffe’s Green Oak Leaves (1923), which had an irrevocable bid and was estimated at $500,000 to $700,000.

Also breaking the million-dollar mark was Childe Hassam’s painting of the Spanish Steps in Rome, Piazza di Spagna, Rome (1897) that sold for $1.2 million compared with an estimate of $500,000 to $700,000.

Another work, Giorgio de Chirico’s Cavallo e zebra in riva a mare, sold in a separate Sotheby’s online auction last week, and three more works from the museum will be offered in June and July. In all, the museum is selling 15 objects.

Thomas Cole, Arch of Nero (1846). Image courtesy Sotheby’s.

The most controversial of the group is Thomas Cole’s The Arch of Nero (1846), which was estimated for $500,00 to $700,000, and sold for $988,000.

“With The Arch of Nero, Cole warned his countrymen about how republicanism was inherently subject to corruption,” dozens of experts, including current and former museum directors and one past president of the Association of Art Museum Directors (AAMD), wrote in a May 10 letter to Newark Museum director Linda C. Harrison.

“The painting urges Americans to be on guard against the dilution and potential dissolution of their republican experiment.”

The Newark Museum was not the only institution to deaccession artworks at the sale (the Brooklyn Museum, the San Diego Museum of Art, and the Palm Springs Art Museum all offloaded art at Sotheby’s), but critics were especially fierce about the New Jersey museum’s decision.

“The Newark sale received prominent attention from the field because it was selling an unusually historically important painting [Cole’s] even as it claimed that it wanted to better represent America’s history in its galleries,” one critic who signed the open letter told Artnet News, on the condition their name be withheld.

“The picture has long been a centerpiece of a fine American collection. Newark mindlessly deleted it. It is important to remember and understand the distinction between deaccessioning and monetizing.”

A representative for the museum said it had no additional comment on the sale, pointing to an earlier statement in which it said that “deaccessioning is a routine and necessary component of the work of any museum.”

Earlier this month, Harrison defended the sales by noting that the works being auctioned represented less than one percent of the museum’s 130,000 artworks. She also said the plan had been “thoroughly considered.”

The Newark Museum and others have been taking advantage of the AAMD’s temporarily looser restrictions around deaccessioning. The label identifying the Newark Museum property at Sotheby’s said it was being “sold to support museum collections,” a term which now encompasses workers’ salaries, building maintenance, and other operating costs. Formerly, the AAMD only approved sales that raised money for acquisitions.

Of the other lots sold by the Newark Museum, a landscape painting by Thomas Moran, Sunset Santa Maria and the Ducal Palace, Venice (1902), sold for $352,800, clearing its high $180,000 estimate. An identical price was achieved for Thomas Eakins’s Portrait of Dr. Joseph Leidy, II (1890), though expectations were far lower for this lot, at just $50,000 to $70,000.

In an unusual move, about a fourth of the way through the sale, the auctioneer announced he was reopening an earlier lot, Charles Sheeler’s Farm Buildings, Connecticut (1941), from the Newark Museum because of a technical glitch. The work eventually went to an online bidder for $315,000 with premium, far below its $500,000 estimate.

Mary Cassatt, Baby Charles Looking Over His Mother’s Shoulder No. 3 (ca. 1901). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Another Newark collection work, Frederic Remington’s bronze Trooper of the Plains, went unsold after bidding failed to rise above $280,000 against an expected price of $400,000. The sculpture, which had no guarantee, may now go back to Newark, but a representative from the museum did not reply to a question about its status.

As for the other institutions, the Brooklyn Museum sold Mary Cassatt’s Baby Charles Looking Over His Mother’s Shoulder (No. 3) (1900) for $1.6 million (also to support its collections); the San Diego Museum of Art spun off Leon Gaspard’s Moonlight-Trading Post-Siberia (1939) for $63,000 and Nicolai Fechin’s Portrait of Anna May Wong (circa 1930) for $478,800; and the Palm Springs Museum of Art shipped off Fechin’s Floral with Daisies (1908) for $478,000.