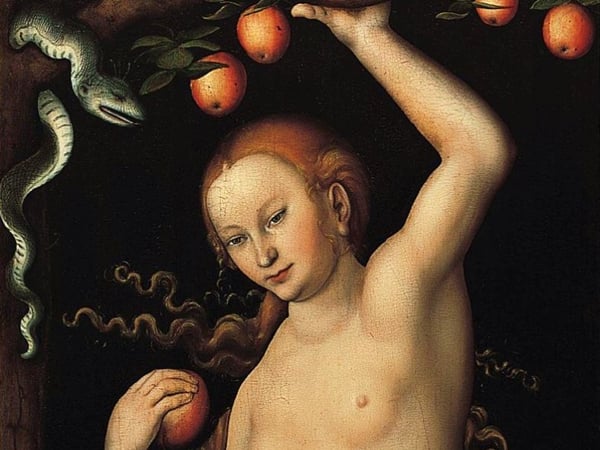

The long-brewing battle over the ownership of Lucas Cranach the Elder‘s paintings Adam and Eve (both circa 1530) will have its day in court: after the Supreme Court’s refusal of an appeal from Pasadena’s Norton Simon Museum (see Supreme Court Declines to Hear Norton Simon’s Nazi-Loot Appeal), California’s District Court has rejected the museum’s motion to dismiss the case.

Marei von Saher, heir to Jewish art dealer Jacques Goudstikker, has been pressing her claim of ownership of the diptych since 2007. Prior to World War II, the oil-on-panel paintings were part of Goudstikker’s over-1,200-piece art collection.

The paintings fell into the hands of the Nazis when Goudstikker fled the Netherlands after the 1940 German invasion. Following the war, Allied forces returned the works to the Dutch government. Goudstikker’s widow, Desi, did not trust that she would be treated fairly by the government and opted not to negotiate for their return.

Complicating matters is the fact that the family of George Stroganoff-Scherbatoff owned the paintings before Goudstikker, until the Stalinist government held an auction of the Stroganoff collection, which the family publicly denounced as unlawful. Stroganoff-Scherbatoff purchased the works from the Dutch government in 1966, later selling them to the Norton Simon.

The California museum, which has owned the life-size paintings since 1971, argued in its motion that because Desi Goudstikker, as von Saher’s “predecessor-in-interest,” chose not to press her claim on the works, the statue of limitations on the theft had expired “some time in the 1950s.” (See Norton Simon Museum Asks Court to Reconsider Nazi Loot Claim.)

A 2006 appraisal placed the paintings’ value at an inflation-adjusted $28.3 million. Cranach’s auction high stands at $8.6 million, achieved at Christie’s London in 1990 ($15.4 million in today’s dollars).

US District Judge John Walter dismissed this claim as irrelevant, noting that a “thief cannot convey valid title no matter how much time has passed.” Because “the subsequent possessor’s acquisition of stolen property constitutes a new conversion,” the court ruled, “the owner is entitled to a new limitations period.”

This backs von Saher’s belief that the case began in 2000, when she learned that the Norton Simon owned the paintings.

In 2012, Walter had dismissed her case against the museum on the grounds that the Dutch government had done its due diligence in trying to return the paintings to their rightful owners, but that ruling was reversed this past June, allowing von Saher to revive her quest for restitution (see Norton Simon’s Nazi-Looted Adam and Eve to Head Back to Court).

In Walter’s latest ruling, he criticized the Norton Simon, noting that “museums are sophisticated entities that are well-equipped to trace the provenance of the fine art that they purchase,” and that “there is nothing unfair about affording plaintiff an opportunity to pursue the merits of her claims against Norton Simon.”

“After carefully weighing the equities, the legislature determined that the importance of allowing victims of stolen art an opportunity to pursue their claims supersedes the hardship faced by museums and other sophisticated entities in defending against potentially stale ones,” wrote Walter. Von Saher, “whose family suffered terrible atrocities at the hands of the Nazis,” he wrote, “will now have an opportunity to pursue the merits of her claims.”