Pace Gallery is teaming up with Art Agency Partners (AAP), a division of Sotheby’s, to represent the estate of the boundary-pushing artist Vito Acconci. The arrangement is relatively new territory for the ultra-competitive art trade, where auction houses and galleries are often at odds in their race to develop uncharted corners of the market.

Marc Glimcher, the CEO of Pace Gallery, and Christy Maclear, who oversees AAP’s artists’ estate and foundation advisory service, say the collaboration illustrates a potentially fruitful way forward.

“Anyone who knows Acconci recognizes the fact that he is of seminal importance but doesn’t have a very strong market,” Maclear tells artnet News. “As an advisor and essentially manager of the estate, we needed a partner who could be a global gallery platform.”

The two entities note that their roles are fairly distinct. Maclear, who came on board first, helped the artist’s wife, Maria Acconci, handle pressing matters after the artist’s death last April, including managing his memorial and identifying a lawyer to settle his estate. She also recommended Pace to Maria, having worked with the gallery as director of the Rauschenberg Foundation until 2016. “I knew that they had a very long-term view, which is our intention in looking for a gallery partner,” Maclear says.

Moving forward, AAP will work with the Acconci Studio to place the artist’s work in museums, develop a strategy for how to promote his diverse bodies of work, and connect scholars directly with his archive and art. Meanwhile, Pace will work to boost Acconci’s market by bringing his art to fairs, organizing gallery exhibitions, and collaborating with cities and parks commissions to build some of his previously unrealized public art projects.

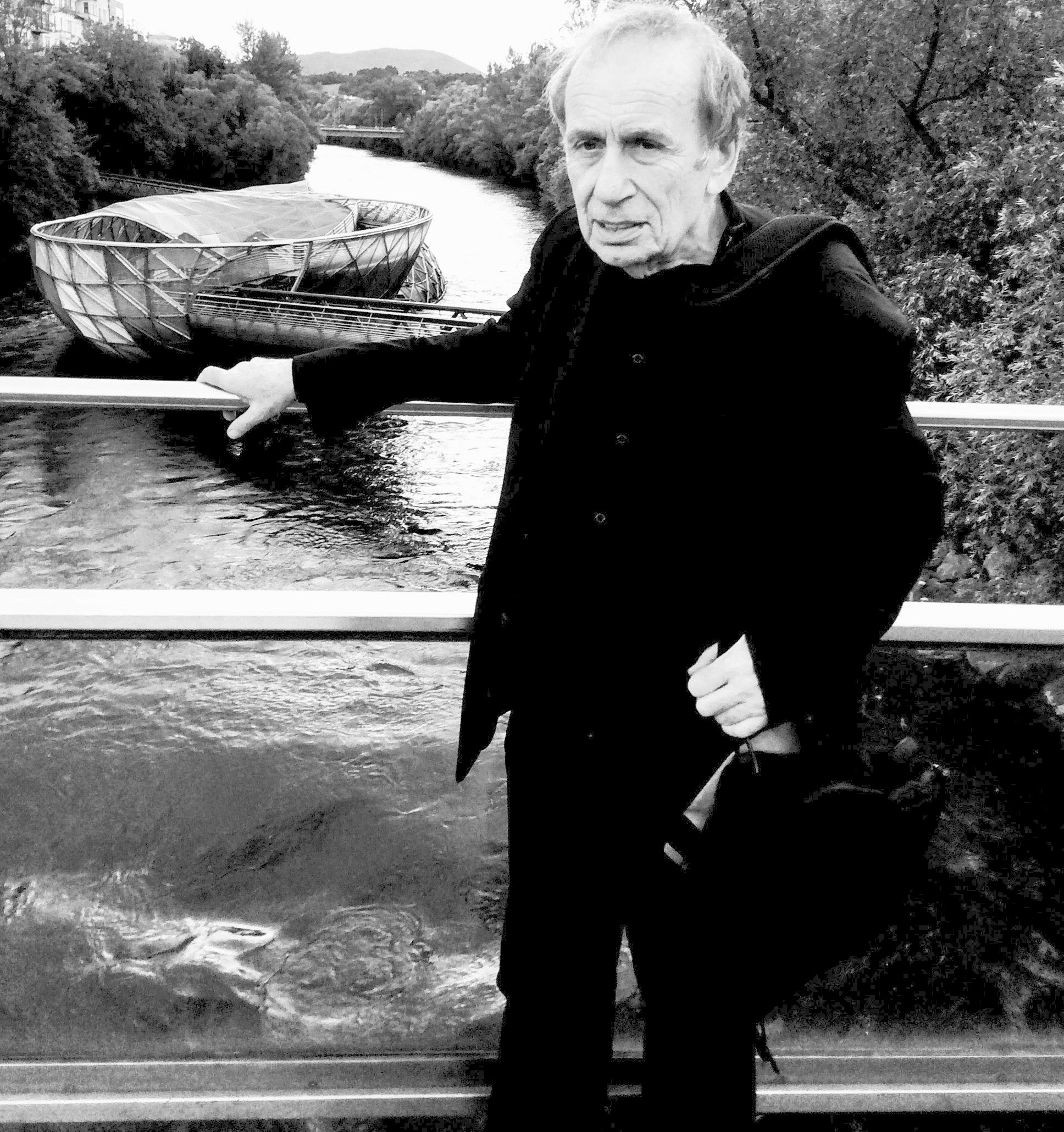

Vito Acconci at Cannon Center for the Performing Arts, ROOF LIKE A LIQUID FLUNG OVER THE PLAZA (Memphis 2004). Photos courtesy of Maria Acconci & Acconci Studio, 2018.

They have their work cut out for them. By his own admission, Acconci was never very concerned with money or the market. His practice ranged from experimental poetry to performance art to radical architecture—none of which is particularly commodifiable. “He was so ahead, we’re just about ready for Vito,” Glimcher told artnet News. “I wish he was here to see it.”

According to the artnet Price Database, Acconci’s work has appeared at auction roughly 240 times. The highest price ever paid for his work at auction is $78,125, realized for a group of photographs and drawings titled Thirty-five approaches (in 45 parts) (1970) at Sotheby’s in 2014.

The new arrangement may surprise those who questioned whether a division of an auction house could ever handle an artist’s estate—historically considered the territory of galleries—without compromise. When the initiative was first announced, Phillips CEO Ed Dolman said the prospect posed “an inherent conflict of interest.”

Notably, Glimcher was among the vocal early skeptics. He told the New York Times at the time that auction houses have an interest only in selling, while “making money is a long-range process with us.” He also questioned whether Sotheby’s had the wherewithal to deal with artists’ personal needs, citing a particularly memorable episode when Jim Dine sent the gallery his shirts to be cleaned. (“You think Sotheby’s is going to do that?” he asked.)

Though Glimcher insists now that his comments were taken out of context, he is pleased that AAP “came to the conclusion that they could work with galleries as partners and that that would be beneficial, and so here we are. Anyway, they were right. That’s the takeaway.”

Vito Acconci’s ROOF LIKE A LIQUID FLUNG OVER THE PLAZA (Memphis 2004). Photos courtesy of Maria Acconci & Acconci Studio, 2018.

AAP, which Sotheby’s acquired in early 2016 for a reported $50 million, has been slowly and quietly building its advisory business since Maclear joined last year. Several other estates, including that of the sculptor Robert Graham, have already come on board, although most have not been made public. They now have 13 such clients and a number of others in contract.

“People are starting to see the need for estate management and advisory services,” Maclear says. “It does not cannibalize the galleries at all. It’s very sympathetic and cooperative.”

Both Maclear and Glimcher acknowledge that their collaboration is only made possible by the rapidly growing, increasingly lucrative, and labor-intensive business of artists’ estates. In 2010, the Aspen Institute reported that assets held by artists’ estates and foundations had grown 360 percent in the previous 15 years to a total of $3.48 billion.

Vito Acconci’s ROOF LIKE A LIQUID FLUNG OVER THE PLAZA (Memphis 2004). Photos courtesy of Maria Acconci & Acconci Studio, 2018.

The management of estates “doesn’t just fall into the ‘guy who sells paintings’ model—it means people who are focused on serving the unique needs of an estate or foundation,” Glimcher says. “It opens up a whole new field.”