Most artists benefit from developing a signature style. Philip Guston refused, departing mid-career from the gestural flourishes that had become a hallmark of his abstract work in favor of symbolically charged figuration. For a while, that abrupt shift seemed to dampen his market—but now, it is likely to secure his place not only in art history, but also in the art-market pantheon.

To date, Guston’s market has not reached the heights of fellow leaders of the New York School of Abstract Expressionism like Willem de Kooning, Mark Rothko, and Jackson Pollock. (The latter’s auction record is more than double Guston’s, at $58.4 million). Robert Manley, the worldwide co-head of 20th century and contemporary art at Phillips, says that while Guston was “as great an artist as any of them,” his market was initially impeded by the decision to change tack.

The move “set his career back in the eyes of many,” Manley says. “He seemed to have ‘betrayed’ abstraction and it took quite a number of years for people to fully appreciate the genius of those later works.”

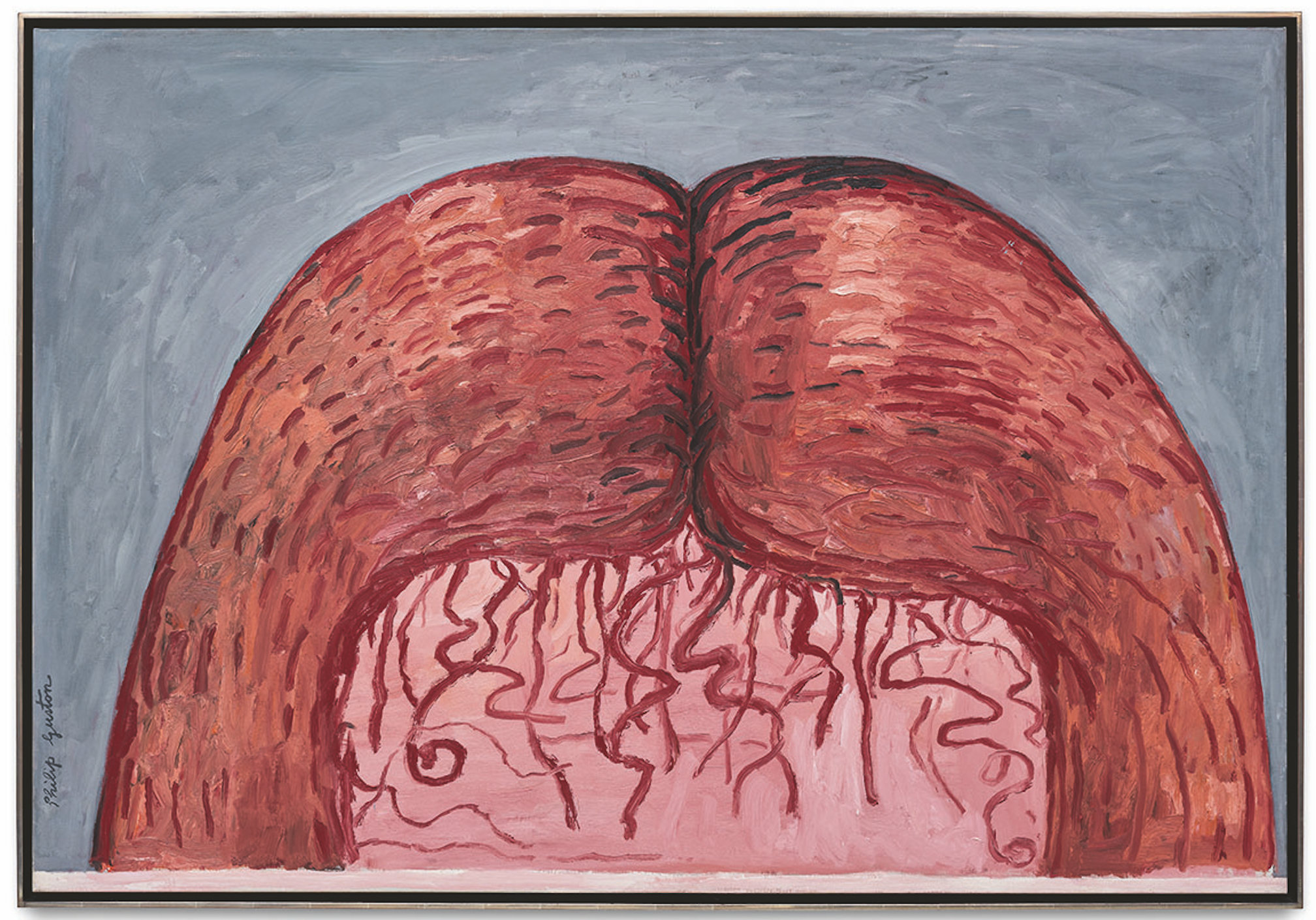

Now, however, with a changing political and art-historical moment—as well as a recent controversy putting him in the headlines—collectors are coming around to Guston’s figuration. A new selling exhibition at mega-gallery Hauser & Wirth, “Transformation,” shows 14 drawings and paintings from both bodies of work side by side. (The show was originally due to open at its St. Moritz gallery on December 23; the IRL opening has now been delayed due to public-health restrictions, but is available online.)

Philip Guston, The Actors V (1962). Photo: Todd White. © The Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy the Estate and Hauser & Wirth.

The Ab Ex Men

While de Kooning, Rothko, and Pollock developed uniquely identifiable styles, Guston pursued starkly different bodies of work throughout his 50-year-long career, from Social Realism in the 1930s and ‘40s to Abstract Expressionism in the 1950s to a return to figuration—though a darker, more politically charged variant—in the late ‘60s. During his lifetime and posthumously, interest in these different bodies of work has fluctuated.

When he was alive, Guston’s Abstract Expressionist work from the 1950s was most popular—and most sought-after by collectors. These works are a key part of postwar American painting and the artist’s own development—plus, they are relatively few in number and rarely come to market. (Many are in museums.) Guston’s $25.8 million auction record was set for one of these—a 1958 work called To Fellini—at Christie’s in 2013.

Naturally, collectors who were used to Guston’s more subtle painterly abstraction didn’t know what to do with this louder, charged, cartoonish work. But political discourses in recent years—and Guston’s growing influence on younger figurative painters—have forced a shift in focus.

“Nowadays, a great figurative painting by Guston is as hotly sought after as an abstract work from the ’50s, and is as high in value and price—if not higher,” says Marc Payot, a co-president of Hauser & Wirth, which has exclusively represented the Guston estate since 2015. The gallery has also worked hard to enhance the position of Guston’s later work, staging five shows dedicated to it since 2016.

Philip Guston, Smoking II (1973), sold for $7.7 million at Phillips on November 14, 2019. Image courtesy of Phillips.

The artist’s most recent top auction prices have also been for late-career works. In 2019, Smoking II (1973), a self-portrait of the artist smoking in bed, sold at Phillips for $7.6 million. Red Sky (1978), which evokes the charged climate of ’60s America through a row of indistinct cylindrical forms evoking a grouping of batons, sold for $7.3 million at Sotheby’s that year, too. Guston’s second highest auction price was achieved for a 1979 self-portrait, Painter at Night, which fetched $12.6 million at Christie’s in 2017.

Today, many consider Guston’s figurative work his signature contribution to art history. Sotheby’s contemporary specialist Emma Baker describes it as his “greatest achievement.”

Controversy—It’s Good for Business

Interest in Guston’s figuration was only enhanced by a controversy this fall, when his 1960s works were the root of a fierce debate. Four museums, including the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC, postponed the artist’s retrospective, which had been in the works for the better part of a decade, due to concerns that they would not be able to properly contextualize a suite of 25 drawings and paintings that depict the Ku Klux Klan. The show is now due to open in 2022.

Several market commentators say that the firestorm, which saw more than 100 artists and intellectuals speak out against the decision and the suspension of one of the exhibition’s curators, might actually help Guston’s market. Manley says that “Guston has always been a respected and well-collected artist, but has been little known outside of the art world. If anything, I think the controversy surrounding the exhibition… might bring it to the attention of a broader public.”

For Payot, the debate only served to cement the artist’s position within art history. “If an artist no longer with us can be so catalytic in current international discourse, and can spark such intense debate and stir such passionate responses, that speaks volumes,” he says. “In the long term, the debate over the retrospective will only benefit the Guston market, including works of all periods in his career.”

Bigger Profile

Philip Guston, Untitled (1968). Photo: Genevieve Hanson © The Estate of Philip Guston. Courtesy the Estate and Hauser & Wirth.

This resurgence of interest in Guston’s oeuvre is reflected in his collector base. Payot says that younger collectors know Guston primarily for “his figurative works, his progressive values, his political and social conscience, his intention to give voice to the things that mattered to him.”

By contrast, “among older, established collectors, Guston has had a consistent place as a modern master.” He also adds that Asian collectors are now seeking works by Guston from “all of the periods of the artist’s career.”

Still, one might think collectors of any age or nationality would balk at the idea of having a hooded Klan figure hanging on their wall. But one 1969 example, Untitled (Red Spot), sold for a mid-estimate $750,000 in October at Christie’s; another, DUO (1970), fetched a mid-estimate $1.4 million at Sotheby’s in February.

Hauser & Wirth expects the market for Guston’s art to be “robust in the future without pause,” Payot says. But one body of work worth watching is Guston’s early material, paintings from the 1930s and ’40s, which predate his Abstract Expressionist period.

These figurative works inspired by Renaissance painting traditions—like Mother and Child (1930) or Martial Memory (1941)—are less familiar to collectors, “but very little has been on the market from this period of his oeuvre, so a comparison is difficult at best,” Payot notes.

Guston’s name is likely not to be far from the headlines in the run up to the 2022 retrospective. As David McKee, Guston’s dealer from 1968 until 2015, put it auspiciously, “Suffice to say that Guston’s market will go from strength to strength as the public continues to realize that he is the most intelligent, most accomplished, and most relevant painter of his generation—and of the last 60 years.”

“Philip Guston. Transformation” is on view now at Hauser & Wirth online. Check the website for updates the show at the gallery’s St. Moritz location.