New Models is an ongoing series that highlights galleries innovating beyond the traditional ways of exhibiting and selling art in the primary market. From forward-thinking collaborative initiatives to novel uses of technology, the concepts it unpacks prove that there are more paths to success and sustainability as an art dealer than the default settings.

When I asked artist and art dealer Stefan Benchoam, director of Proyectos Ultravioleta in Guatemala City, to describe the art scene in his home country, he quoted from a nature journal he’d read recently: “Birds sing in the morning to communicate to each other that they survived the night.” Artists from Guatemala, he said, are doing the same. “After everything we have experienced, we are using art to reflect on what has happened and what continues to happen in this troubled history,” he added, referring to the decades of political instability and civil war that were instigated by the U.S.-backed coup d’etat in 1954. The strife only came to an end in the mid-1990s.

Benchaom is a cofounder of what is perhaps Guatemala’s preeminent art gallery, as well as one of the most dynamic spaces to emerge on the global scene following the 2008 recession. Operated by Benchoam alongside Jennifer de León, Enrique Morales Larraondo, and Margo Porres, Proyectos Ultravioleta was a newcomer at Art Basel this year, and its artists are gaining visibility at key institutions: the gallery represents acclaimed Guatemala-based painter Vivian Suter and the estate of her mother, multimedia artist Elisabeth Wild, as well as key voices from Indigenous communities like Edgar Calel.

Rosa Chavez / Vivian Suter “Firt Sunrises on Earth,” Guatemala City, 2021. Photo credit: Margo Porres. Courtesy of the artist and Proyectos Ultravioleta, Guatemala City

Now located in a 1940s-era residence in Guatemala City with tiled floors in earthy floral patterns and stained glass doors that separate gallery spaces, Proyectos—UV for short—does not quite fit the white cube model, but neither does the gallery’s modus operandi.

Part of that stems from its unique approach, which is to move at a slower pace. Dealers spent a year discussing how to price and sell a work by Calel—a sacred installation and an offering to his ancestors—that would go on view at Frieze London in 2021. In the end, Tate agreed to buy the work via a custodianship, meaning it would take on shared caretaking of the piece together with Calel’s community, instead of acquiring it outright.

Vivian Suter exhibition in October 2021. Photo credit: Brotherton Lock. Courtesy of the artist and Proyectos Ultravioleta, Guatemala City

Kunsthalle Sud

Set up as an artist-run project space in 2009 (Benchaom is an artist listed on the gallery’s website), Proyectos Ultravioleta was an early cornerstone for a young, post-civil war art scene that was hungry for contemporary perspectives.

“Art is completely different in different parts of the world,” Benchaom said. “It becomes rapidly conflated with money in Europe and the U.S., but in Guatemala and in the Global South, art is about connection. It helps people heal.”

The gallery’s current exhibition by Guatemalan artist Jessica Kairé, titled “Nothing Concrete,” is an excellent example. It presents collapsible fabric monuments that reference famous Guatemalan memorials. They can stand tall, held up by a few performers, and can be easily folded up again or hung delicately from the ceiling.

Benchaom founded the gallery with Byron Mármol, Juan Brenner, and Rodrigo Fernández as a clubhouse of sorts funded by post-opening parties with a cash bar and music. The aim, they said, was to run a Guatemalan version of a kunsthalle, even if, internationally, the space would function as a commercial gallery.

From the onset, the handful of collectors in Guatemala took notice. One of its first exhibitions featured work by artist Naufus Ramírez-Figueroa, who went into political asylum in the 1990s in Mexico and then Canada. The presentation was an iconoclastic reading of the monarchy, pastiched with nostalgic and subcultural Canadiana. Though the founders initially had no hope of selling locally, a prominent Guatemalan collector surprised them by offering to buy a sculpture. The gallery had no sales model to speak of—so the collector bought it directly from the artist’s studio for less than $2,000 and ended up deciding to give a small donation to Proyectos Ultravioleta.

From top left, clockwise Stefan Benchoam, Jennifer de León, Enrique Morales Larraondo, and Margo Porres.

Sustainable Growth

The gallery has come a long way in the decade since, sensitively scaling up and slowly professionalizing its business model while maintaining its core aim of being an arts organization for the Guatemala City scene. Given their prioritization of program over profit, curators from abroad have taken note: gallery artist Ramirez-Figueroa, for example, has gone on to show at Haus der Kunst in Munich and has a solo exhibition this summer at Museum Leuven in Belgium.

And, surprisingly or not for such a curatorially-minded space, Proyectos Ultravioleta’s fair booths are nearly as notable as their in-house exhibitions. In 2019, the gallery was awarded the top prize in the Focus section at Frieze London for its presentation of heavy, woven textile works, made on a loom that drew from traditional Mayan weaving methods, by Guatemala City artist Hellen Ascoli.

Benchaom tends to think of the fair presentations as exhibitions, given that attending fairs in places like London, New York, or Basel has become a crucial element to contacting the outside art world. Indeed, it’s where most of the art world first encountered them.

“The advantage of being in Guatemala is that the overheads are lower than in other cities,” Benchaom said. “The disadvantage is that the whole infrastructure to support artists is super complicated.” Shipping costs, which have only grown since the pandemic, are higher, and fewer people come through the door.

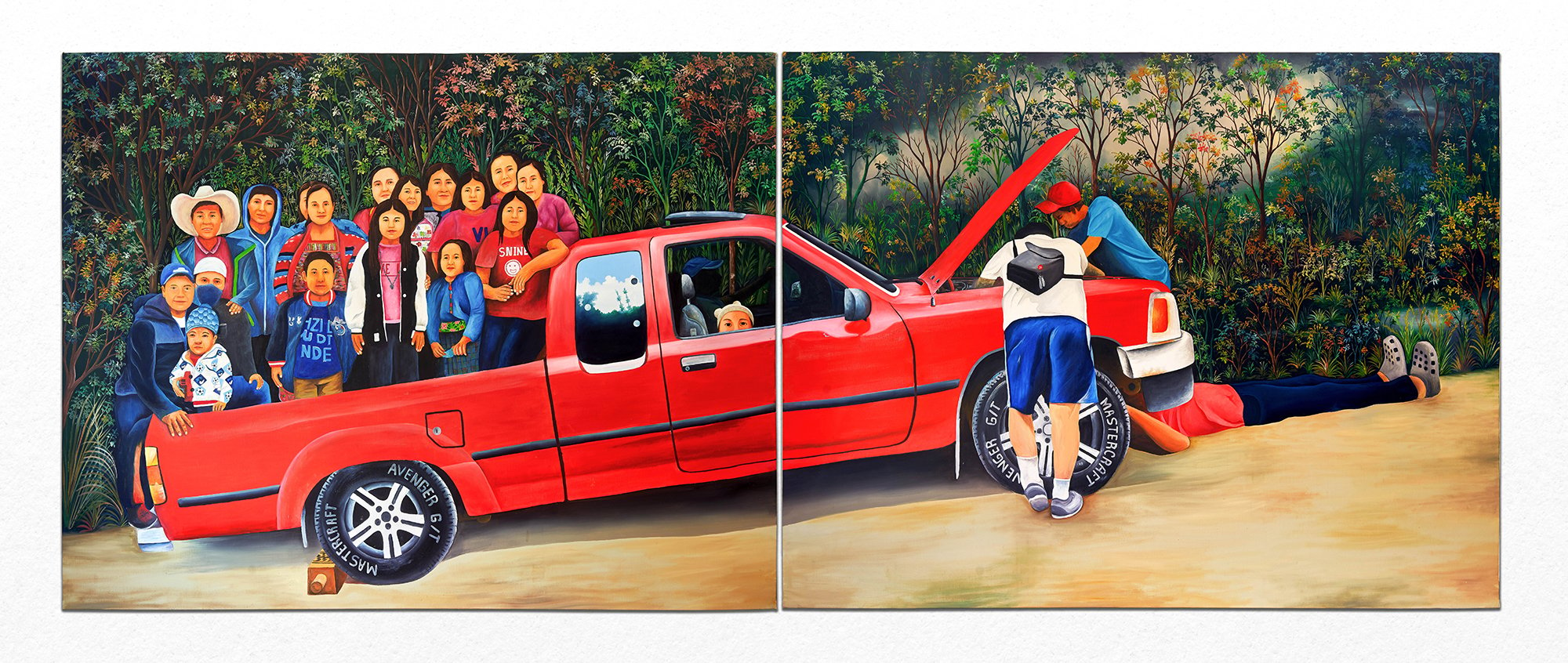

“The Greenness of the Land” by Edgar Calel at Art Basel Statements, 2022. Photo credit: Gina Folly. Courtesy: Courtesy of the artist and Proyectos Ultravioleta, Guatemala City

Though the program is mainly focused on Guatemalan artists, it is also international. Palestinian duo Basel Abbas and Ruanne Abou-Rahme were the main focus of a booth at Frieze New York; the presentation was organized like a small retrospective.

“They have open-ended reflections on what it means to be Palestinian, and all the difficulties and impossibilities of carrying that nationality. But they do this in a way that is personal, emotive, and intelligent,” Benchaom said. “When you experience one of their installations in person, you are moved and it very generously connects to other struggles of other peoples.”

The gallery reached a new rung on the market ladder by attending Art Basel this year with a solo exhibition by Calel, who made headlines after his presentation at Frieze the year before with the 2021 installation Ru k’ox k’ob’el jun ojer etemab’el (The Echo of an Ancient Form of Knowledge), the ancestral offering bought by Tate.

The Echo of an Ancient Form of Knowledge, (Ru k’ ox k’ob’el jun ojer etemab’el), 2021. Photo courtesy of Frieze

The works by Calel, who comes from a Mayan Kaqchikel community in the Guatemalan Highlands, ranged in price from $2,500 to $35,000. Though the purchasing concept here was more straightforward than for his booth at Frieze London, Benchaom said the gallery is still cautious about in whose hands such intimate works end up.

“It is about matching works with the right people,” he said. “There is always this pressure to grow and hit these benchmarks, but we wanted to do it in a way that really spoke to us and that felt sustainable. I hate to use the word, but I will: our main clients are not necessarily collectors, but the artists themselves. The art market is not core to our essence.”