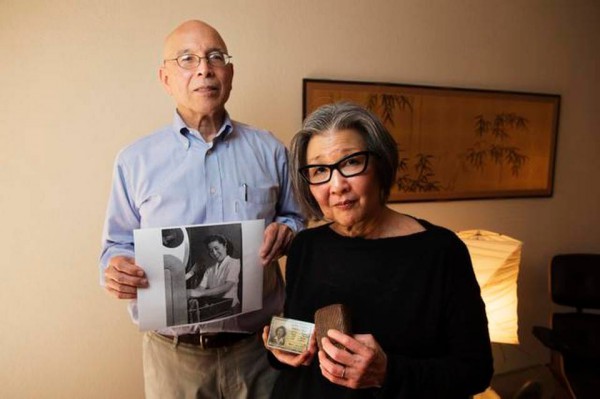

Photo: Paul Kitagaki Jr, courtesy the Sacramento Bee.

[/caption]

After protests by Japanese Americans and advocacy groups (see Auction of Internment Camp Art Sparks Widespread Outrage), New Jersey’s Rago Arts and Auction Center has cancelled today’s planned sale of artifacts from the internment camps that held Japanese Americans during the Second World War. It’s the second controversial World War II–related auction to be scrubbed in recent weeks (see Auction House Withdraws Terrible Hitler Flower Painting).

“We know what the internment camps were,” founding partner David Rago told the AP. “We know that it was a disgraceful period in American history, but we did not understand the continued emotional impact embodied within the material. We just didn’t get it.”

Rago was auctioning the approximately 450-piece collection, which was amassed by late crafts historian Allen Hendershott Eaton during research for his 1952 book, Beauty Behind Barbed Wire: The Arts of the Japanese in Our War Relocation Camps, on behalf on an anonymous consignor.

The decision not to move forward with the auction is sure to please the over 6,700 people who signed a Change.org petition calling the sale “a betrayal of those imprisoned people who thought their gifts would be used to educate, not be sold to the highest bidder in a national auction, pitting families against museums against private collectors.”

San Jose representative Mike Honda, who was interned in a camp, praised Rago’s decision not to hold the auction, telling the San Jose Mercury News “these items belong with the families, or in museums so future generations can learn from them.”

A Rago spokesperson told the New York Times that the auction house will continue to work with the consignor “to see this property go where it will do the most good for history.”