Yet another lawsuit has been filed by a photographer against a major artist, and the case could have a significant impact on the interpretation of copyright and intellectual property law.

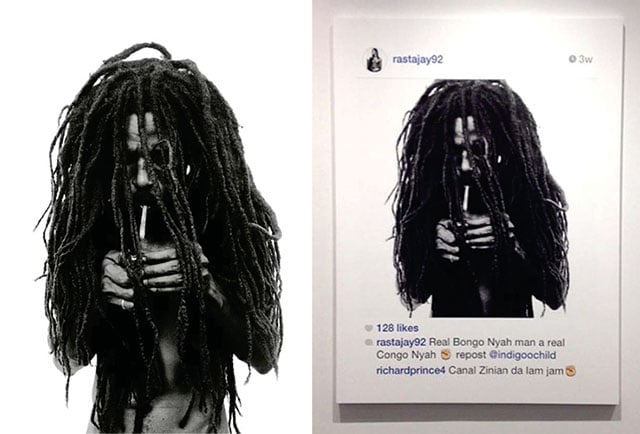

Photographer Donald Graham has brought suit against Richard Prince for using a photographof a Rastafarian, taken by Graham, in his 2014 Gagosian Gallery exhibition “New Portraits,” which presented prints of other people’s Instagram posts, with comments by Prince. Prince obviously has a taste for this kind of image; the major lawsuit Cariou v. Prince (in which French photographer Patrick Cariou sued Prince and his dealer Larry Gagosian for copyright infringement) centered on Cariou’s pictures of Rastafarians.

In that case, the Second Circuit court of appeals found that 25 of the 30 “Canal Zone” paintings under consideration were “fair use” of Cariou’s photographs and thus did not infringe on Cariou’s copyright. The parties settled out of court with respect to the remaining five paintings, which means that judges did not issue rulings on the questions of intellectual property at issue, which, in the view of some experts, was a missed opportunity for further clarification of the law.

The new case is distinct from Cariou v. Prince in some important ways. In phone conversations and e-mail exchanges, three attorneys who focus on intellectual property law outlined its significance.

“One of the interesting differences between this case and Cariou v. Prince has to do with the fourth prong of the fair use test, which looks at the market impact of the infringement,” says Amy Goldrich, of New York firm Cahill Partners. The fair use provision of copyright law allows for the use of copyrighted material under certain conditions, for example, if the subsequent work has significant new content or if it does not impinge on the market for the original works.

“Cariou had made no fine art prints of his work and hadn’t exhibited them as prints, whereas the Graham complaint alleges that he has only sold his work as prints, and ‘has never licensed the copyrighted photograph or made it available for any commercial purpose other than for sale to fine art collectors.’ That’s one big distinction between this case and Cariou v. Prince. If the case doesn’t settle, then a court will determine whether this makes a difference in relation to the market impact standard.”

The fair use provisions also allow for new work that includes significant commentary. We asked Stanford Law School professor Paul Goldstein whether the fact that the new photographs come from a major social media platform could bear on the question of whether Prince’s work is transformative because of that new context and since the prints include Instagram’s framing and comment field. He was not convinced of its qualifications as fair use.

“It is a basic rule of copyright law that infringement is measured not by how much the alleged infringer added but by the amount of the copyrighted work that he took,” said Goldstein, and in fact Prince’s photographs lift a large portion of Graham’s image. “So Prince’s modest additions don’t, as a fundamental matter, excuse what he did.

“Even in the Second Circuit, where this case is being brought, and which has the most liberal standard of fair use and the most liberal, open sense of transformative use, I don’t think this one makes it as fair use,” said Goldstein. “One tent-pole decision to consider is Cariou v. Prince, which involved more substantial changes to the image. Here, there is no change in the image, though there is modest change in the framing.

“If he’s commenting on social media, let him take things other than copyrighted images,” said Goldstein. “The attraction of [Graham’s] image for Prince is not that it’s taken from Instagram, but rather that it’s a truly arresting image. Looking at the images he used, they’re all pretty compelling images. The credit for that goes to the original author. There’s no justification for getting on the back of a copyrighted work to make your comment—and I’m not sure what the comment is.”

One of the shortcomings of current copyright law, some experts say, is the dependence on simple formal comparison of the works at issue, which doesn’t sufficiently account for the commentary Goldstein is discounting in Prince’s work. A group of foundations even filed an amicus brief in the Cariou v. Prince case, pointing out that conceptual and appropriation art can’t be judged solely on its formal and aesthetic properties.

“It’s the art-law equivalent of Zombie Formalism,” NYU law professor Amy Adler says.

Attorney Claudia Ray, of New York firm Kirkland & Ellis, isn’t so sure things will go Prince’s way in the new case.

“Mr. Graham’s lawsuit against Richard Prince for infringing the copyright in his photographic portrait of a Rastafarian offers the intriguing possibility of a ‘do-over’ of Patrick Cariou’s similar claims that Mr. Prince infringed the copyrights in Mr. Cariou’s photographs of Rastafarians,” said Ray. “For one thing, in the prior case, the Second Circuit left to the district court whether what it described as ‘minimal alterations’ were a sufficient basis for concluding that five of Mr. Prince’s works presented a ‘new expression, meaning or message’ such that the works qualified for the fair use defense.

“Here, the Complaint’s exhibits suggest that there were few if any changes to the underlying image itself,” Ray points out. “If that turns out to have been the case, it will be interesting to see what the court does with what the Complaint presents as very literal copying.”

Ray also points out that the market for work by Graham may have greater overlap with Prince’s; he is represented by a Paris gallery and has shown his work at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and the International Center for Photography.

“Another question is what if any impact Mr. Graham’s track record as a fine art and commercial photographer will have on the legal issues,” she said. “The Second Circuit in the prior case, in ruling for Mr. Prince as to most of the works at issue, found it significant that Mr. Cariou had ‘not actively marketed his work or sold work for significant sums,’ but it is hard to imagine a court reaching the same conclusion here. Ultimately, the case has the potential to answer the question of whether any photographer can succeed on a claim involving so-called appropriation art. And thus it is sure to be closely watched.”

Goldstein puts the potential impact of the case in even stronger terms.

“If you can get away with this,” he asked, “what is left of copyright?”