Salman Toor is the best kind of contemporary painter: funny, insightful, and not afraid to get personal. His colorful, figurative images are both intimate and relatable, featuring crowds of people engaging in romantic or imaginative adventures, filled with references to the artist’s many travels and international background. Born in Pakistan in 1983 and living and working in Brooklyn today, Toor received his MFA in painting from the Pratt Institute in 2009, and uses a variety of visual languages inherited from both Eastern and Western pop culture.

Toor’s recent exhibition “Resident Alien” is still on view at Aicon Gallery in New York, through December 5—so don’t miss your chance to see it in person.

Where did you grow up, and what role does your culture play in your work?

I grew up in Lahore, Pakistan, and moved to the United Sates for college. I see myself as a traveler wandering between boundaries and working with the fruitful dissonance, understanding and confusion that comes with leaving my community of origin. The culture of that community is at a crossroads, with a shifting sense of belonging and an intense debate about its identity. There a physical and intellectual war between monolithic idea of religion and a flexible humanistic one. Those issues are a part of my work.

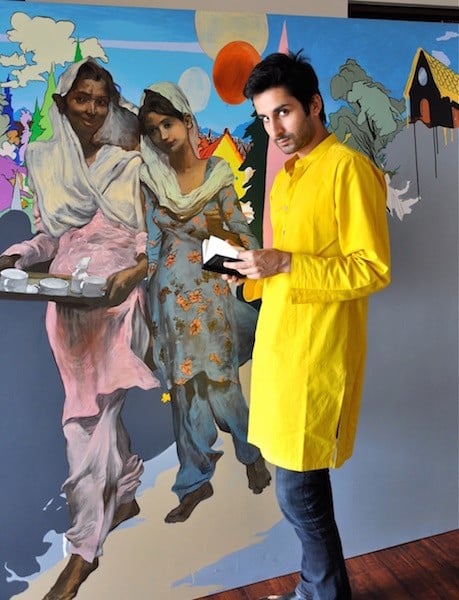

Salman Toor, Transliteration Game (2015). Courtesy of Aicon Gallery.

You received your BFA from Ohio Wesleyan University. What was the transition to the Midwestern United States like?

It was completely mad! I had arrived straight from the din and dung and bustling beauty of Lahore to the Methodist cornfields of Ohio. I wandered around in a daze for the first year, absorbing Americanisms. But soon I found my community in a hippie commune, a crumbling Victorian house where clothing was optional, everyone painted, drew, or made music, and my formative relationship with art history and painting began. I found an exciting similarity between Sufi ideals of asceticism and beauty in this now-defunct American tradition from the 60s.

Your work is like a crash course in Art History 101. What are some the movements you draw inspiration from?

When I moved to New York in 2006, I became an apprentice to the best moments of about three hundred dead Italians, Spanish, and Flemish geniuses, and also eventually the Islamic galleries when they opened in 2011 at the Metropolitan Museum. So those years of apprenticeship come through in a lot my work, which is the result of a self-taught academic training, and a study of the tradition of graphic novels and historical miniature manuscript illuminations from Iran and South Asia.

I like the risks of painting without a plan, using intuition and memory to create imaginary worlds that explore this surreal space where deeply personal and political concerns intersect. This invasion of the political into the personal is inevitable, growing up in a region which is seething with social upheaval, where it isn’t possible to remain neutral or apathetic for long. The paintings of David Salle and Brice Marden became something like solutions for quagmires in my practice.

The narrative paintings of Indian artist Bhupen Khakhar also have a special resonance for me. The freedom of multiple perspectives appeals to me because it points to the self as a protean, uncertain, and unsingular being. For me, his work is a connection between South Asia’s tradition of naive truck art, historical miniature painting and the history of Western European oil painting.

In my own work I try to merge the freedoms enjoyed by artists in the Persian and Indian miniature painting tradition, vis a vis the use of aerial or multiple perspectives and the liberal use of text as a seamless part of the image, an image that moves readily between abstraction and representation.

Salman Toor, The Burden (2015). Courtesy of Aicon Gallery.

Can you talk about the use of text in your work?

The text in the paintings is multilingual—at times gibberish, other times consisting of verses from 17th century Sufi poetry. They are extraordinarily contemporary poems on being an outsider in multiple worlds, on the disruption of the rigidly of religious and cultural rituals that divide, and the illusive nature of the divine. Some of the poems I use are by Bhulleh Shah, a wandering Sufi dervish from Punjab (a fertile province between Pakistan and Northern India) in the 17th century, or are by the contemporary poet of exile, Hasan Mujtaba, whose work points to the shape-shifting nature of longing and belonging.

My use of text also recalls memories of graffiti around the alleyways and mosques of Lahore. I hope to point at the daily ritual of reading and feeling without literally understanding—a rite of passage for most Muslim children who read the Quran in Arabic. It is a way of learning by sound and imagination, a kind of spiritual learning. (Some call that brainwashing, but that’s debatable.)

Some of your paintings contain ghost-like figures. What do they represent to you?

I see them as apparitions of cultural baggage, imagined histories and memories. For instance: skinny hobos with their belongings, crossing the borders of the Partition of India, begging Indian princes, disapproving matrons, Jane Austen, a member of the British Indian Army, an eighteenth century European physician. I see these people as the fabric of a new history of colonization and cross-cultural pollination, a history which is now open to interpretations and edition from parts of the world outside the United States and Western Europe.

I see these ‘ghosts’ as agents of change and enablers of a reinvention of self and belonging. They are imagined ancestors and actors in a fractured, nonlinear history in which an imagined past is present now, a past that is both disruptor and enabler.

Salman Toor, For Allen Ginsberg (Diptych) (2015). Courtesy of Aicon Gallery.

Describe an average day in the studio.

Within two seconds of walking into the studio it is clear to me if I’m going to trash or keep the work I’ve done the day before. If I decide to keep working on it, and I work on two pieces at one time at the most, walking back and forth while looking at the picture as though sizing up a dangerous bully, which is exactly what an empty canvas is to me. Then I gather courage and take a leap of faith with a loaded brush and a vague idea and usually, four hours later I have something I can finally like, at least tentatively. If work is going well, I resentfully go down to the deli for a sandwich and usually the transaction with Egyptian immigrants working the cash machine and asking me where I’m from becomes a kind of fuel of ideas that I take back to the studio with me.

Later, friends drop in and we pop open a bottle of wine and share the war wounds of working in the studio all day before heading out to local haunts for dinner around Bushwick or the East Village.

What kind of music do you like? What artist or album are you currently listening to?

Soundtracks are my thing. The ‘Drive’ soundtrack by Cliff Martinez and the Wagner soundtrack to ‘Melancholia’ are perennial favorites. A tad depressing, but hey! they put me in a calm trance which is essential to get me in the mood to work. I also like 90s dance music and traditional Ghazals from Indian and Pakistani masters for the after hours.

If you could have dinner with any person, living or dead, who would you choose?

I would choose the quintessential 17th century Mughal king, Jehangir, the richest man in the world during his lifetime, a collector of exotic animals from all over the world and an amateur scientist. I would love to ask him many things over a modest meal of sushi— which I’m sure he would detest, but I would insist he try it as I mixed a spritz for him to taste, and tell me what he thought.

I would ask him details about his first meeting with the first English ambassador to India, Sir Thomas Roe. The accounts of this near-allegorical meeting—preserved in Roe’s diaries and Jehangir’s court gossips—are unforgettable. Of these two cultures, one would be eventually crushed completely by the Industrial Revolution of the other. I would ask Jehanghir what he really thought about the presents of jewels and liquor that the ambassador offered to him. According to accounts, he wasn’t afraid to look bored with the paltry pearls and said, frankly, that he was only really interested in the thoughtful liquors from Western Europe.

Roe, meanwhile, had refused to do a full prostration in front of the king, instead asking for a number of ritual bows and curtsies as he approached the throne. I would love to hear Jehanghir’s account of all this.

I would ask him what he thought of the grunge of East Village, the collection of his very personal family albums and tunics in the glittering museums of Sir Thomas Roe’s country, and finally, what he thought about this country. I would ask him what he thought of my t-shirt, with its dancing Michael Jackson cartoon, and skinny jeans. I would show him pictures of the industrializing, globalizing world and the crumbling tombs of his cousins and ancestors in present-day Pakistan and India on my iPhone.

I think he would begin to weep and take a gulp of his Campari and call me a gracious host.

Salman Toor, 9pm, The News (2015). Courtesy of Aicon Gallery.

Tell us about The Comic Project.

I’m working on a graphic novel with my friend, Alexandra Atiya, who is a writer. It will be called The Electrician. Some of the drawings from this ongoing project were shown at Honey Ramka gallery earlier this year. It is a story charting the inner lives of the members of a middle class family in Lahore over the course of a week. Steeped in the supernatural, the novel highlights the theme of social conflict in contemporary Pakistani life.

What has been the highlight of your career or personal life so far?

The highlight of my career so far would have to be a vision of Francesco Clemente entering my little studio—stoic, standing at ease, and then giving a chuckle at a deliberately kitschy painting of a maid waiting on a sleeping, half-naked master in Lahore. That was a year ago. I would never have imagined that he would go on to write an essay for the catalog of my current show.