One of the main events on the March calendar in Paris is the Salon du Dessin (through April 1), the annual Drawing Fair that attracts not just the world’s most prominent dealers of works on paper, but also, in recent years, exhibitors who contribute to the breadth of scholarship in the various fields related to drawing.

At this year’s fair, now in its 28th edition, art lovers can satiate their curiosity for everything from 18th-century sanguines on brown paper to watercolors by Modern artists. But they can also enjoy museum-quality exhibitions of drawings that are not on sale and are rarely seen by the public.

The show’s venue is a majestic Neoclassical structure built between 1808 and 1826. Construction began under Napoleon and the building was ultimately named after the architect who drew its original plans, Alexandre Théodore Brongniart, a commissioner in charge of public works in 19th-century Paris. (He also died before it was finished). With its soaring 90-feet ceilings and marble floors, the venue served for over a century as the seat of the “Bourse de Paris”—the Paris stock exchange—before being converted, after the exchange closed in 1996, into a conference and exhibition center.

This year, joining the 39 international exhibitors, are the Musée Carnavalet, a local museum dedicated to the history of Paris, and Chaumet, the historic Place Vendôme jeweler. Both have pulled a selection of rarely seen drawings from their reserves and archives.

Joseph Chaumet, wheat and oat drawing (around 1890). Courtesy Collection Chaumet, Paris.

The Musée Carnavalet, which is closed for renovations, is showing an exhibition titled “Paris est une fête” (Festivities in Paris) of works depicting festive scenes, from royal ceremonies to street parades, that revive ambiances of Paris as a “Movable Feast” from the 17th to the 20th century.

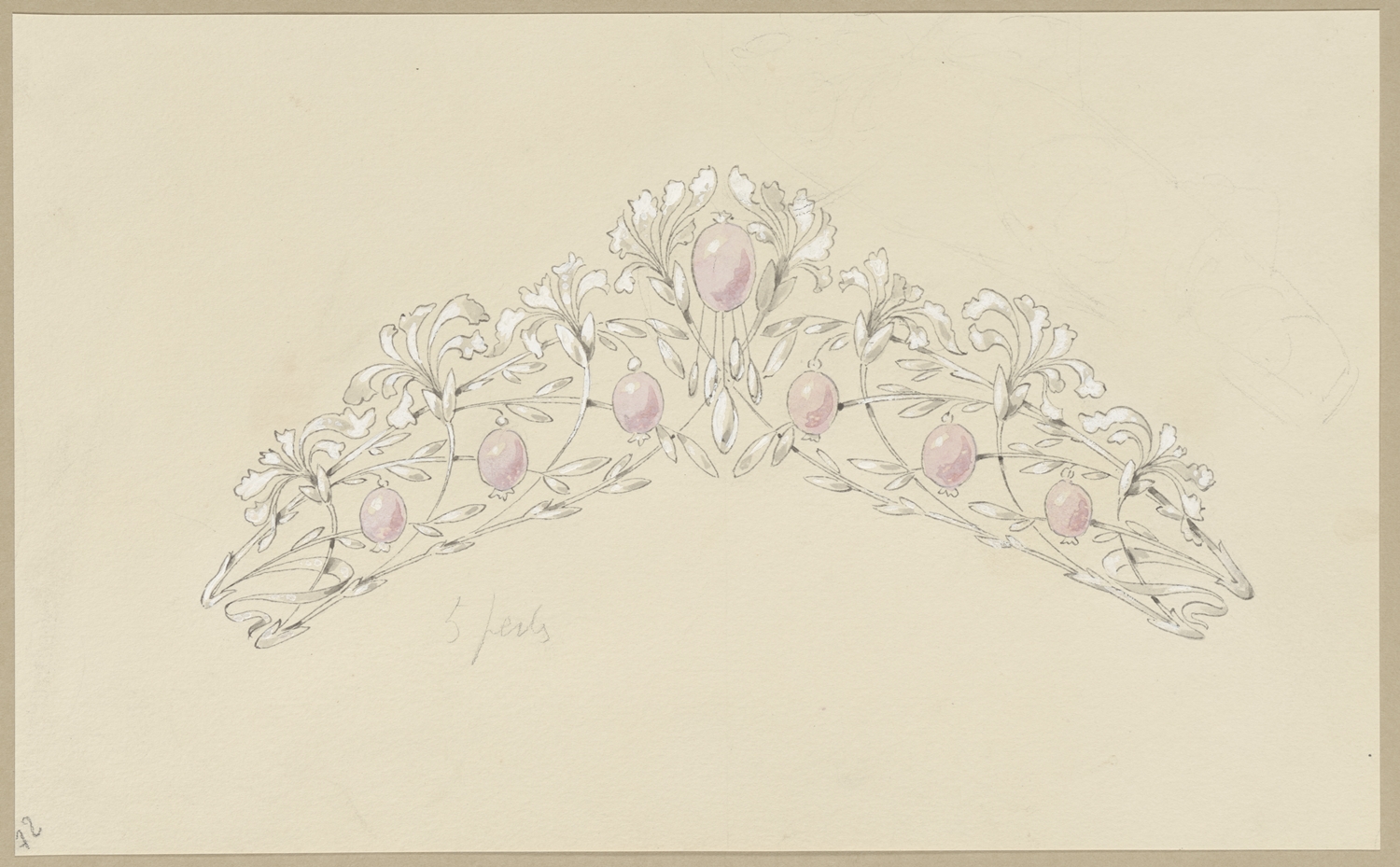

The Maison Chaumet, founded in 1780, is presenting “Chaumet: Nature Drawing/Design,” which includes drawings from 1830 to 1920 on the theme of nature. The works were selected by Chaumet’s new director of patrimony, Claire Gannet, who collaborated with a botanist, Marc Jeanson, as co-curator. Since 2013, Jeanson has served as director of the National Herbarium at the Museum of Natural History in Paris. In 2017, he was a curator of another nature-celebrating exhibition titled “Jardins” at the Grand Palais.

The 38 works in the exhibition are but a minuscule sampling of the 60,000 drawings in the vast archives of Chaumet, one of the first Parisian jewelers to settle on the Place Vendôme. They consist largely of technical drawings and gouaches of finished jewelry, and demonstrate brilliantly the dexterity, fertile imagination, and keen eye of Chaumet’s in-house draftsmen. Their repertoire of flora and fauna in a variety of drafting techniques shows the intricate stages of creating jewelry—starting with reproducing the shapes of nature, then matching its colors to precious stones—and allowing their grace and character to shine through.

“Jeanson brought a scientist’s vision to a choice of drawings that are ultimately art ‘objects,’ and his viewpoint stirred us in choosing from particular categories those drawings that resonated with us symbolically, as in the case of those representing certain flowers, insects, wheat or reeds, which are foundational images for Chaumet,” Gannet said.

Stalks of wheat bending in the wind—fertility and prosperity symbols at Chaumet—were the inspiration for one of the maison’s most iconic pieces, the Épis de Blé tiara created in 1811 for the Empress Marie-Louise.

Épis de blé tiara, François-Regnault Nitot (circa 1811), in gold and silver set with diamonds, Collection Chaumet Paris.

“Our first muse, the Empress Josephine, was herself a prominent botanist, and instrumental in importing many varieties of seeds into France and planting her own garden at the Chateau de Malmaison,” Gannet said.

The era best represented in the show is the 19th century, when naturalistic jewelry with motifs of fruits, flowers, and foliage became fashionable thanks in part to developments in botany but also to the importance of nature in the Romantic movement in art, illustrated in the fair by Eugène Delacroix’s Branches of Physalis, a black pencil and pastel on tan paper (circa 1840), shown by the Paris-based Galerie Nathalie Motte Masselink.

“Mistletoe” brooch project (around 1900). Courtesy Collection Chaumet, Paris.

Delacroix, whose retrospective closed in January in New York at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, painted flowers throughout his career in an age marked by rampant industrialization. They were from his own garden in Champrosay, and later from just outside his atelier in Paris’s 6th arrondissement, where he moved precisely for its idyllic garden.

Flowers also fascinated Henri Matisse, who a century later produced his Flowers (1945) gouaches, on view at the Parisian Galerie AB’s stand. Two nearly identical works belong to a small series the artist drew at the request of Michel de Brunhoff, a former editor in chief of Vogue France.

“Brunhoff had asked Matisse, van Dongen, and Derain for drawings to illustrate his book titled Parfum,” said Agnès Aittouarès, Galerie AB’s founder. “Matisse produced five gouaches representing flowers because for him, perfume meant flowers. They expressed Matisse’s idea of pleasure, and as you can see they dance on the page, they are alive.”

Chaumet will bring its own nature-inspired jewelry creations alive in an upcoming show that will feature a large selection of historic pieces alongside their corresponding drawings at its Musée Éphémère. The show, which opens on April 17, tells the story of 200 years of the maison’s creations through the delicate strokes of its in-house draftsmen.