During the mid–1800s, vaudeville acts were popular amongst frontier settlements of the United States. They were usually a combination of comedy theatre and music acts. Burlesque was born from certain theatre productions that had women wearing revealing costumes. Audiences had mixed reactions to burlesque, ranging from acceptance to disgust. Richard Grant Wright said in his 1869 article “Age of Burlesque”:

“The peculiar trait of burlesque is its defiance both of the natural and

the conventional. Rather, it forces the conventional and the natural

together just at the points where they are most remote, and the result

is absurdity, monstrosity. Its system is a defiance of system.”1

Burlesque performances, although taboo to certain audiences, were seen as a form of entertainment that was not overly gratuitous. Burlesque performers began to multiply. The term pinup came into play when performers left behind photographic business cards to be pinned up on the wall or stuck into mirror frames. Historically, the Victorian age has been known as the era of repression, but this has mostly been a myth. Publicly, they were demure, but in private they were relatively okay with sexual exploration. Burlesque remains popular today.

Although pinup photography existed, pinup illustration was more commercially available. Charles Dana Gibson (American, 1867–1944) created one of the earliest forms of pinup illustration, known as the Gibson Girl. She was the image of idealized beauty in the early 20th century. She was proper, self–confident, and maintained an alluring gaze to the viewer. The Gibson Girl represented mischief as well as liberation from tradition.

Charles Dana Gibson, Young woman with straw hat, 17.5 in. x 13.5 in.

After World War I, the Gibson Girl was no longer relevant. Women were more socially independent. Flapper culture allowed them to lose some of the modesty displayed by the Gibson Girl. During this time, pinup illustrations changed into the style we recognize today. The term “cheesecake” also started being used synonymously with pinup. It originated in the 1930s as a female alternative for the term “beefcake,” which refers to attractive photographs of men. Although one of the most widely known and recognizable pinup artists was Alberto Vargas (American, 1896–1983), his predecessor, George Petty (American, 1894–1975), was publishing the new form of pinup as early as 1933. Petty studied art at the Paris Académie Julian until the start of World War I, when he was forced to return to the United States. He worked as an airbrush retoucher and freelance artist for magazines. When he was hired at Esquire magazine, he started to publish his own style of pinup girls. Petty girls, which were collected by GIs who were abroad during the war, were depicted with arched backs and wore sexualized outfits. After he left Esquire, the artist was replaced by Alberto Vargas.

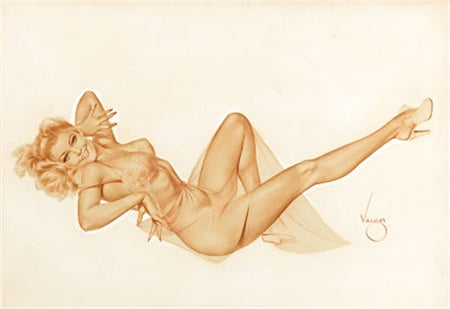

Born in Peru and later based in New York, Vargas also furthered the image of the new ideal pinup girl. Before his time at Esquire, the artist worked for a number of years as a freelance commercial illustrator, and had created artwork for the film industry. The October, 1940 issue of Esquire printed Vargas’s first illustration and it received overwhelming praise. This soon led to the first Vargas girl calendar, which sold more copies than any other previous calendar; the artist’s work has been highly sought after ever since then. In 1953, Vargas was hired as an artist for a new publication called Playboy, where he stayed until 1974.

Alberto Vargas, Varga Girl, c.1940–1959, 14.8 in. x 21 in., sold for US$30,000 at Heritage Auctions on October 13, 2012

Pin up art was not just art for men to gawk at. Throughout history, there have also been female pinup artists. Zoe Mozert (American, 1904–1993) was one of the top pinup artists during the mid–20th century. She was a contemporary of both Petty and Vargas. Mozert studied at the Philadelphia Museum School of Industrial Art and moved to New York City in 1932 to work as a freelance artist. During the 1930s, she designed covers for pulp magazines such as True Confessions. In 1945, she moved to California and worked as an art adviser and painter in the film industry. Mozert often used herself as a model for her paintings and drawings. Unlike her colleagues, she depicted more realistic views of women, while still painting them nude or in sexy outfits. The poses were more natural. Often times, pinup artists would alter figures to make them sexier; Mozert seemed to keep the original look of her models.

Zoe Mozert, Cowgirl with toes in the stream, 1960, 22.5 in. x 28.2 in.

One of the living legends of female pinup artists is Olivia de Berardinis (American, b.1948), who is professionally known by just her first name. Olivia attended the School of Visual Arts in 1967 and studied under Chuck Close (American, b.1940). Her work was mainly Minimalist, but she started to paint cheesecake art in 1974 for financial reasons. Eventually, pinup became the main focus of her artistic interests. She was inspired by the jazz burlesque choreographer Bob Fosse, and the drawings of women she created before attending art school. Many of her paintings use the famous model Bettie Page as the subject. Olivia also creates works based on the performances and photographs of Dita von Teese, one of today’s foremost burlesque performers and models. Many of her paintings show women as powerful and confident, similar to how superheroes are depicted in comic books.

Pin up art has a long and rich history that continues to thrive today and has permeated the mainstream. It is no longer reserved for men’s magazines. Some see pinup art as one of the factors that helped amplify the sexual conversation during the 1960s, and many artists today continue to create art in this style.