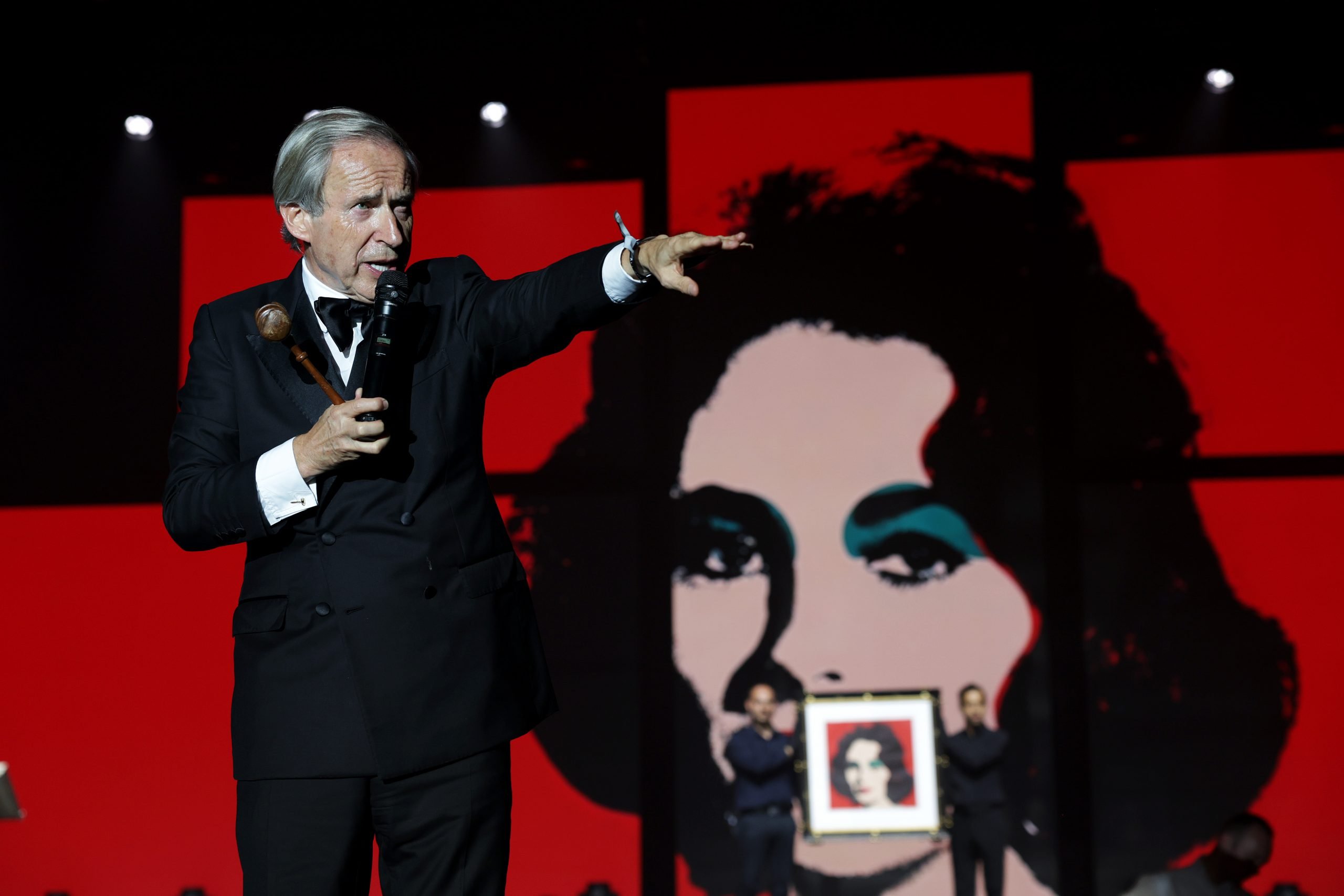

Every month in The Hammer, art-industry veteran Simon de Pury lifts the curtain on his life as the ultimate art-world insider, his brushes with celebrity, and his invaluable insight into the inner workings of the art market.

As an art market professional I am regularly asked to physically inspect works of art in preparation for valuations and inventories. This requires me to spend a fair amount of time in warehouses, storage facilities or freeports. There, more often than not, I experience art in the worst possible conditions.

Under harsh, artificial lighting, you sometimes see piles of unframed paintings stacked against each other and you witness works being unpacked and repacked in front of your eyes. Of course this doesn’t alter the objectivity of my exceptional eye, and of my razor-sharp artistic judgement! At least, so I like to think, but I have to admit that presentation and context have a not insignificant subliminal impact on one’s assessment.

In 1979, I became the curator of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection, which was then the largest private collection in the world, and is today housed at the Museo Nacional Thyssen-Bornemisza in Madrid. I had to oversee the traveling exhibition of 57 seminal old master paintings going chronologically from Duccio to Fragonard. It opened that year at the National Gallery in Washington D.C. and subsequently travelled to Detroit, Minneapolis, Cleveland, Los Angeles, Denver, Fort Worth, and Kansas City before ending two years later at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. I thought I knew these works inside out, but when I saw them installed by different curators and museum directors in nine leading American museums, my perception of some of them evolved. They seemed to look different in every venue. I realized then that the art of installing an exhibition is of paramount importance in creating the optimal circumstances of appreciating art.

When I was at the helm of Phillips during the first decade of the current century, we had the luxury of having vast exhibition facilities in New York’s Meatpacking District. This gave us the chance to install each auction preview exhibition, as if it were a permanent installation at a world-class museum such as the MoMA. Giving works the space to breathe—particularly by artists we championed such as Koons, Hirst, Wool or Condo, or designers such as Arad, Newson, and Hadid—subliminally contributed to their stratospheric rise.

It possibly played an even bigger role for the careers of the many artists that we introduced to the secondary market such as Bradford, Peyton, Grotjahn, Fischer, Brown, Weiwei, Nara, Kelly and many more. Most of them now get sold in evening sales of the main three auction firms, which means they do get the necessary care for their installation. Most works by emerging artists, however, get sold in day sales, and their installation is definitely not on the same level. Very often, the paintings are plastered side by side on the walls. This does a disservice to the artists who do not benefit from the Rolls Royce treatment that their more established—and more expensive—colleagues get. This is like sending your clients to a flea market and expecting them to pick the few relevant works.

How a work is presented and described in a physical catalogue is equally vital. Now that, luckily from an environmental point of view, most of the auction catalogues are online only, how a work appears on your iPhone, iPad or PC is essential since that is your first ‘contact’ with the work itself.

Context is equally crucial. World records for Russian giants like Ilya Kabakov or Eric Bulatov were obtained once their works were no longer being hung next to the works by other Russian artists but next to the ones of their international peers such as Gerhard Richter, Andy Warhol or Jean-Michel Basquiat. Fernando Botero, who is probably one of the globally best known artists, used to be sold in the context of sales devoted to Latin American art. His prices began an ascent that still has significant room to grow upwards, once Sotheby’s and Christie’s began including them in their main international evening auctions. (Cf. a recent article by Katya Kazakina, and recent LinkedIn post by Christie’s CEO Guillaume Cerutti).

A seemingly even more random aspect that influences our perception of a work of art is its aura. Paintings, sculptures and works of art are made of energy exactly like us humans. We should therefore not be surprised that the aura of inanimate objects can evolve and alter in the same way that ours does. As a very young man, I often felt that, after leaving a girlfriend’s house in the morning, every woman I passed on the street seemed not only incredibly attractive but also somehow attuned to my aura. Conversely, after a heartbreak, I could be at an event filled with some of the world’s most beautiful women and feel no attraction toward any of them—and, more importantly, receive no interest from them in return.

When last year the Fondation Louis Vuitton staged the blockbuster Mark Rothko show, the public was unanimously oohing and aahing. The main reason was of course the intrinsic beauty and spiritual quality of Rothko’s oeuvre—but the fact that the value of each work was between $40 million and $80 million didn’t hurt the perception. There are of course plenty of examples of artists for whose work there was red-hot demand and for whom the prices have fallen back to the level of what they initially cost, or below, on the primary market. When we now look at the same works we have to admit to ourselves that we are maybe not quite as moved as we were before. Understandably, I do not wish to give any specific examples.

Promotional image for the reality TV show Work of Art: The Next Great Artist.

One further subliminal element that influences our appreciation of a work is how we feel personally at the time of looking at it. That has strictly nothing to do with the quality of the work.

From 2010 to 2012 I participated as mentor in two seasons of ten episodes each in the reality TV show ‘Work of Art – The Next Great Artist’ that was coproduced by Sarah Jessica Parker and aired on Bravo. China Chow was the host, star art critic Jerry Saltz and gallery owners Bill Powers and Jeanne Greenberg Rohatyn were judges. In order to select the twelve contestants for each season we interviewed several hundreds of hopeful artists in Los Angeles, Miami, Chicago, and New York. Some of them had spent the whole night before waiting with a portfolio of their works in long queues outside the art schools where the interviews took place.

Each artist had three minutes to make an impact before the next would be called up. We judges sat behind a table and turned down the vast majority of them. This process, while fascinating, was strenuous as it lasted endless hours. Occasionally we would stop for a coffee break to regain some strength. We were surprised to realize that the majority of candidates we had greenlighted for the show had all made their pitch shortly after the various coffee breaks. Is it pure coincidence that the best candidates showed their work at this time? No—we must honestly admit that the caffeine and sugar rush, which reenergized us after the breaks, made us see the candidates in a much better light.

I do my profession because I am driven by my obsession for art, but as in everything else, tiny details can make the difference between failure and success.

Simon de Pury is the founder of de PURY, former chairman and chief auctioneer of Phillips de Pury & Company, former Europe chairman and chief auctioneer of Sotheby’s, and former curator of the Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection. He is an auctioneer, curator, private dealer, art advisor, photographer, and DJ. Instagram: @simondepury.