After much anticipation, the small-but-mighty sale of 12 star works from the collection of the late Anne Bass did not disappoint.

At Christie’s New York on Thursday, every one of the Impressionist and Modern works offered from the collection of the philanthropist and former wife of oil billionaire Sid Bass sold (known as a white-glove sale in auction parlance). Altogether, they brought in a hefty total of $363 million, just above the high estimate of $361 million.

Then, just after that event, Christie’s held another sale, of 20th-century art, that drew enthusiastic, if not equally frenzied, bidding, which we’ll get to later.

First, the Bass sale. The highest-priced lot was Claude Monet’s Le Parlement, soleil couchant (1900-03), widely regarded as one of the finest paintings from the artist’s prized London series. It was estimated at $40 million to $60 million and, after auctioneer Adrien Meyer opened the action at $22 million, it was chased by at least five Christie’s specialists on the phones.

Claude Monet, Le Parlement, soleil couchant (1900-03). Image courtesy Christie’s.

In the end it came down to stiff competition between a client of the auction house’s global president, Jussi Pylkkanen, bidding via telephone, and the Nahmad family of art dealers, seated as usual toward the front. Pylkkanen ultimately won the work for for $66 million (just under $76 million including premium).

The work now ranks as the fifth most expensive Monet painting ever sold at auction, according to the Artnet Price Database.

A pair of red Rothkos were also undeniable stars of the sale. Together, the two guaranteed works brought in a total of $116 million, compared to the combined low estimate of $105 million.

Mark Rothko, Untitled (Shades of Red) (1961). Image courtesy Christie’s.

Bidding felt more lively for offerings such as a bronze Edgar Degas sculpture, a rare Petite danseuse de quatorze ans from 1927, that carried an estimate of $20 million to $30 million. It was chased by two Christie’s executives bidding for clients on the phone, from its opening mark around $14 million to a final bid of $36 million ($41.6 million with premium).

Christie’s second sale, of 20th-century art brought in a total of $468 million. Of 42 lots on offer, 41, or 98 percent, were sold.

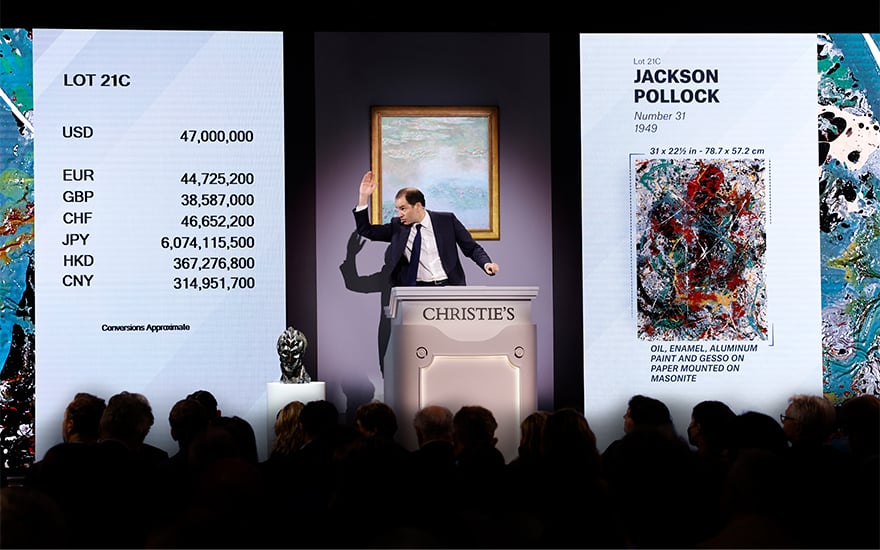

Many of the highest priced works at the auction sold right around their low estimates, including the top lot of the night, Jackson Pollock’s luminous drip painting Number 31 (1949), created when the artist was at the height of his fame. The unpublished estimate was in excess of $45 million, but the only bid that could be gleaned in the saleroom was from a Christie’s specialist on the phone bank, and the hammer came down quickly on what appeared to be a single bid at $47 million (or $54.2 million with fees).

Vincent Van Gogh, Champs près des Alpilles (1889). Image courtesy Christie’s.

It was a similar scene for the second-highest lot of that sale, Vincent Van Gogh’s Champes pres des Alpilles, which was expected to sell in the region of $45 million. The price was at that level when Meyer tried to coax bids from two members of the auction house’s executive team, beamed in on a screen from their Hong Kong phone bank. After a confusing series of signals and waves, Meyer joked in response “Hi, how you doing?” and, when it was clear no competition was forthcoming, he brought the hammer down. The final price with premium was $52 million.

At least 15 works had irrevocable bids in place, meaning they were backed by outside bidders, and it’s safe to assume a fair number of those backers went home with their respective works. The cumulative low estimate on works with outside guarantees was just under $148 million.

Notably, one of two works withdrawn from the sale, a Gustave Caillebotte boat scene that carried a low estimate of $6 million, had already been guaranteed by Christie’s a while back,

Pablo Picasso, Tête de femme (Fernande (Conceived in 1909). Image courtesy Christie’s.

Another highlight of the night was a rare Picasso sculpture of his “first great love,” Fernande Olivier, according to the Christie’s catalogue. Tête de femme (Fernande), conceived in 1909, is being deaccessioned by the Metropolitan Museum of Art after patron Leonard Lauder gave the museum a similar one. The funds will be used for other acquisitions.

The work was backed by a third party or outside irrevocable bid and estimated to sell for about $30 million. It was hammered down for $42 million ($48.5 million with premium).

At least one buyer, bidding through Pylkkannen, scooped up two masterpieces: a snowy Monet winter scene, La Mare, effet de neige (1874-1875), for $25.6 million, and, just two lots later, Joan Mitchell’s large abstract canvas Untitled (circa 1969) for $8.9 million.

An unexpected highlight of the night came during the competition for a painting by celebrated, but far lesser known American artist Ernie Barnes, whose painting The Sugar Shack (1976) shows a group of people dancing exuberantly at an iconic dance hall, the Durham Armory in 1952, in segregated North Carolina.

The relatively modestly priced work carried a pre-sale estimate of $150,000 to $200,000 and was backed by a guarantee from Christie’s. Auctioneer Meyer put the audience on notice when he said there were “22 telephones” lined up to bid.

Ernie Barnes, The Sugar Shack (1976). Image courtesy Christie’s.

But almost as soon as the bidding opened, two would-be buyers seated just a few rows away from each other in the room, engaged in a spirited and tenacious bidding war that quickly rose the work’s price from six figures, to seven, and finally eight. The hammer price ended up at $13 million (with premium $15.3 million). Barnes’s previous auction record, set in 2021, was $550,000.

The winning bidder, who audibly identified himself to the nearby bank of press, is Bill Perkins, described by various online sites as a hedge fund manager, film producer, and high-stakes poker player, could be overheard saying “we got what we came for.”

Emanuel Leutze, Washington Crossing the Delaware (1851). Image courtesy Christie’s.

Since auction houses have recently been organizing sales according to time periods, there can be some unlikely bedfellows, and nowhere was this more evident than in the inclusion of Emanuel Leutze’s classic Washington Crossing The Delaware, the most famous version of which is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

This one had an estimate of $15 million to $20 million and was ultimately won by contemporary art aficionado Alex Rotter, Christie’s chairman of the 20th and 21st century departments, for a phone client. He outbid competing fellow executives, including those who specialize in more historic art categories, for $39 million, or $45 million with premium.