“I think one of the biggest ideas that I would put out there is really trying to use and harness this technology to redistribute power—these interlocking systems, whether it’s museums, collectors, free ports, auction houses, etc. I also think that one of the really beautiful things is the way in which this technology builds community. That’s something that is beautiful. It can be everlasting.”

— Cheryl Finley, professor, curator, and writer

Beatriz Ramos was working as a commercial illustrator building billion-dollar corporate brands when she and Judy Mam, a writer, began discussing a particular inequity in the art world: Artists built value creatively that they did not own. Artists could put their portfolios online and “people would give you a like,” as Mam said, but at some point, as Ramos said: “If we want artists to form a community, we need to give them the tools to do what they do best, which is make art.” Ramos and Mam imagined a global collective of artists making work together. The impetus for founding their platform, DADA, was to nurture creativity and to gather people together. To join the community, you had to respond to someone else’s drawing with a drawing of your own—to participate in a visual conversation with others.

DADA was founded in 2014, well before broader consciousness of NFTs. Mam and Ramos conceived of this digital community as a space where artists could draw, create, and connect with one another. To their surprise, they found that people liked the creative freedom of drawing with strangers from all over the world—not fearing being judged by close friends but experimenting.

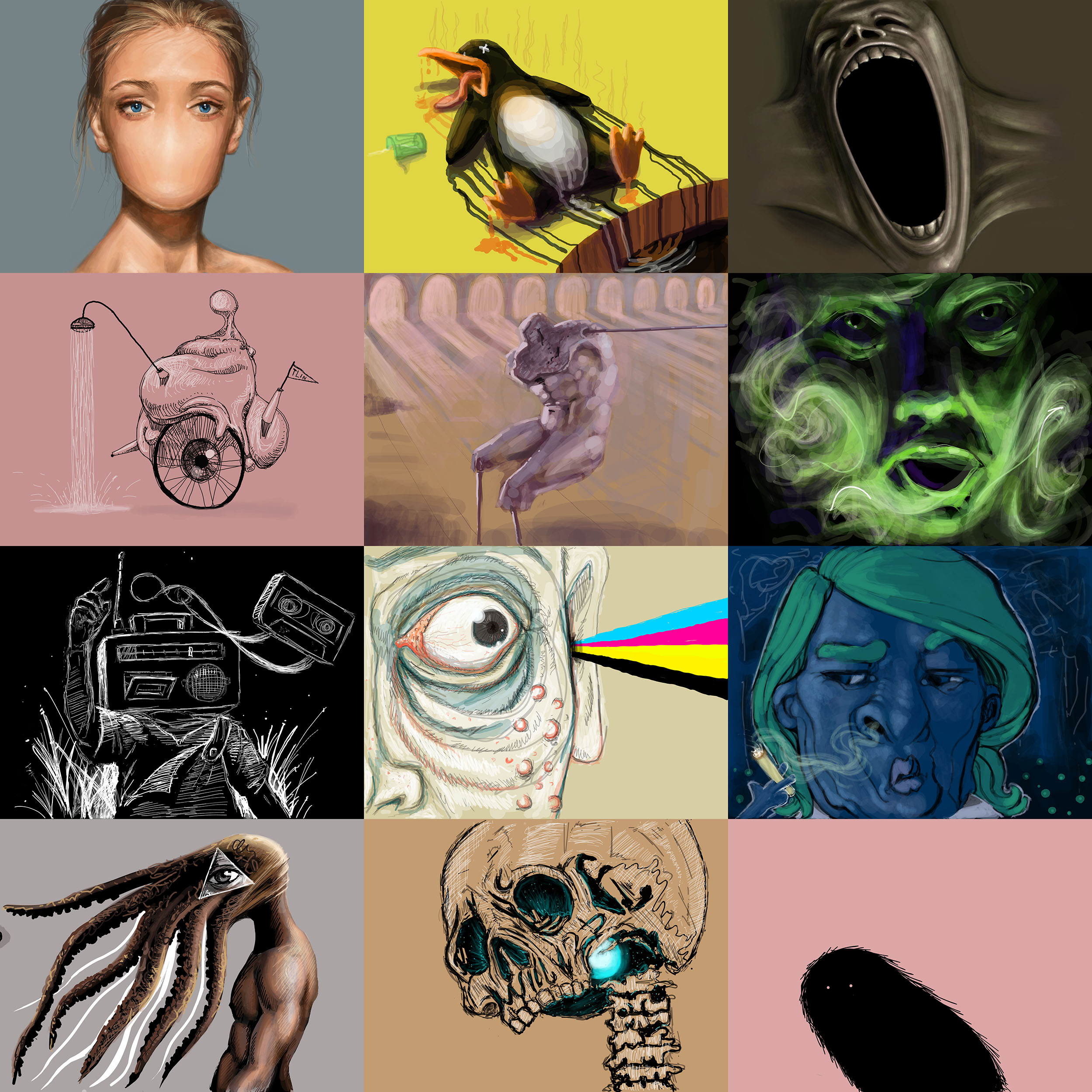

The first DADA collection of NFTs, Creeps & Weirdos, evolved from multiple artists in multiple conversations and was curated by Ramos and Mam. When asked about the title, they said it was because, considering the imaginative forms that these visual conversations had spawned, “some were creepy and some were weird.” The name arose from Ramos and Mam’s desire to create a “coherent collection to be tokenized.” They were aware of the “creepy weird aesthetic” of Rare Pepes, leading them to choose “that creepy, weird aesthetic on purpose.” They launched the project on Halloween 2017, which included secondary sales royalties for artists embedded into the smart contract, and have since reinvested monies raised from sales of their NFTs back into their community.

Later, DADA started a different kind of conversation: a series of “Invisible Economy” working groups. They envisioned a future in which art-making could be radically separated from the market and that a shared underlying economy could benefit the entire community from the value created by its members. Ramos and Mam imagined that, although the works could be sold individually, a larger percentage of the sales’ proceeds would go into a fund that would be distributed among all the active participants in the community, providing a form of universal basic income. Mam told us, “Although at first individual artists received 70 percent of the primary sales and 30 percent of secondary sales, today all the proceeds from the sales of DADA’s tokenized collections go to a general fund where they will be distributed among all the participating members of the community including technologists, according to their contributions.” In other words, they organized a collective version of artists’ resale rights, the percentage of a secondary market sale that goes back to the artist, in primary and secondary markets.

DADA’s pioneering work adding automated royalties for artists also catalyzed a structural change regarding how NFTs are transacted: A group of artists led by Sparrow Read and Matt Kane was instrumental in the establishment of royalty standards for NFT platforms such as SuperRare and OpenSea.

The cover of The Story of NFTs: Artists, Technology, and Democracy. Photo courtesy of Rizzoli Electa.

The questions of DADA get at the heart of the political potential of blockchain: Can it create new avenues of support for artists individually and, in fact, create forms of collective ownership, of shared upside, and of surplus that can be reinvested in artistic futures? We find ourselves in a situation where the world is changing rapidly and we’re inside the changing world. As a result, the most critical thing to do is not to answer the questions but instead to try to ask and engage with the right ones.

One of these key questions is how these new forms of economic sustainability can come about through fractional equity and resale royalties. A second question is how collaboration and community practice are being built around these systems of royalties and asset formation not just by artists but by other disinvested communities. Here, the questions are not solvable individually, but only by coming together with others. This necessity of collective action may bring about huge shifts in the power structure and huge potential for community governance models.

These questions center the democracy stories of blockchain—issues of redistribution, participation, inequity, and inclusion. While there may not yet be clear answers to these questions, the importance of asking them was the impetus for our series. These questions are the subject of Whitaker’s research—and that of many other scholars and practitioners we were lucky to invite in. Our purpose here, in Abrams’s term—and image!—is to curate the giant 40-scoop sundae of questions of the future, questions we could never answer alone, but that unite these intersecting stories of blockchain and lay out clear choices for how we choose to design the future.

Excerpted with permission from The Story of NFTs: Artists, Technology, and Democracy by Amy Whitaker and Nora Burnett Abrams, published by MCA Denver and Rizzoli Electa.