Installation view, Tauba Auerbach, “Projective Instrument,” 2016.

Photo courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery.

1. Tauba Auerbach at Paula Cooper, through February 13.

“Projective Instrument,” an elegant and exciting show of new works by San Francisco-born artist Tauba Auerbach, features large-scale abstract paintings as well as table-like sculptures which hold curious glass objects that resemble scientific instruments. Auerbach was inspired by a 1915 treatise by American architect and theosophist Claude Bragdon, in which he outlined a system for representing four-dimensional ornament on a two-dimensional plane.

With consummate craftsmanship and a visionary’s intensity, Auerbach translates Bragdon’s proposals into a unified iconography that resonates throughout the show. In the sculptures, Auerbach transforms Bragdon’s “ornaments” into three-dimensional “instruments.” The paintings as well as the three-dimensional works highlight repeated patterns—lines and shapes alluding to the vortex and the helix, thus to movement and the passage of time. A number of the glass pieces, resulting from Auerbach’s recent residency at Urban Glass in Brooklyn, are refined and imaginative interpretations of the ancient Greek “meander” pattern; only now they convey, with ultra-cool precision, a rather menacing beauty.

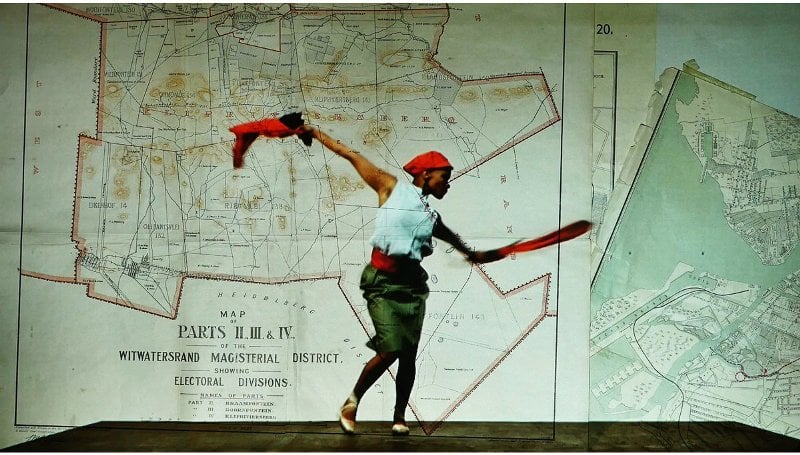

William Kentridge, Notes Toward a Model Opera, video still, 2015.

Photo courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery.

2. William Kentridge at Marian Goodman, through February 20.

Two recent multichannel video installations by William Kentridge, More Sweetly Play the Dance, and Notes Toward a Model Opera, are quintessential and rather spectacular works to make their US debut. As in previous endeavors, the South African artist lends his distinctive, hyper-theatrical amalgam of live-action footage and stop-motion animation of his line drawings in video installations that are as poetically seductive as they are politically engaged.

Filling the large front gallery, More Sweetly Play the Dance is projected on eight floor-to-ceiling screens spanning three walls. Kentridge offers an immersive experience as viewers join in an on-screen parade of shadowy figures that the artist describes as part carnival, protest, and exodus. The hypnotic procession is accompanied by brass band and accordion music that is alternately celebratory and funereal. Some of the figures hold cut-out images of silhouetted heads and animals, which echo the black-painted steel relief sculptures Kentridge displays in a side gallery.

Hyper energetic, if not exactly upbeat in tone, Notes Toward a Model Opera, in the rear gallery, debuted in Beijing in mid-2015. The artist was inspired in this work by the revolutionary operas and ballets that Madame Mao promoted in China in the late 1960s through the mid ’70s. Kentridge provides school desk chairs for visitors to study a pulsating three-channel video featuring images of ballet dancers, often in revolutionary period garb, superimposed upon flashing textbook pages, and Kentridge’s drawings of birds in flight—all writhing in a feverish quest for freedom.

Catherine Opie, 700 Nimes Road (Bedside Table), 2010-11.

Photo courtesy Lehmann Maupin.

3. Catherine Opie at Lehmann Maupin, through February 20.

This enthralling two-part exhibition presents a distinctive set of works that Los Angeles-based photo artist Catherine Opie has produced over the past few years. Known for her provocative exploration of gender identity, and an often acerbic critique of the urban environment, Opie appears in this show in a rather meditative or introspective mode, although the images are potent and engaging as ever. The gallery’s Chelsea branch features recent portraiture, and hazy landscape photos that are both romantic and classical in tone. They often aspire to painterly attributes. Outstanding among the portraits, for instance, are artist celebrities such as Matthew Barney, Lawrence Weiner, and John Waters, who are dramatically lit in a manner that is decidedly Rembrandt-esque.

Filling the gallery’s Lower East Side branch is a series of fifty photographs titled 700 Nimes Road that is an understated but surprisingly moving tribute to the late Hollywood icon and AIDS activist Elizabeth Taylor. Opie received permission from the actress to photograph the interior of her home in the months just prior to her death in 2011. In the exhibition, as well as an accompanying book (DelMonico Books/Prestel), Opie focuses on intimate details of the place, such as a number of vignettes, or clusters of photos and memorabilia throughout the house that are tributes to her family and close friends, such as Michael Jackson (Bedside Table). One particularly poignant image highlights a casual heap of bejeweled red ribbons, alluding to her glamour, and, of course, to Taylor’s early and valiant efforts on behalf of AIDS awareness and research. While Opie never got the chance to photograph the star, she manages to convey in these photos a sense of her luminous presence.

Installation view, Ann Veronica Janssens, 2016.

Photo courtesy Bortolami.

4. Ann Veronica Janssens at Bortolami, through February 20.

Gorgeous in its seeming nothingness, this show of recent works by Ann Veronica Janssens is tightly composed and functions as a single ethereal yet transformative installation. The individual components of the exhibition don’t sound like much—a pile of blue glitter strewn on the floor; a couple of rectangular pieces of corrugated metal roofing protruding from high up on two walls; gold-painted Venetian blinds; and a pink spot-lit room with attendant haze from a concealed fog machine.

On closer inspection, the British-born, Brussels-based artist offers an allegorical experience of nature in this show, which coincides with Janssens’s solo exhibition at the Nasher Sculpture Center in Dallas. The abject-looking corrugated panels here, each titled Moonlight, prove to be precious objects—in fact, aluminum covered in platinum leaf. The blinds constitute a gold-leaf covered allusion to the sun, while the sparkling pile of blue glitter effortlessly evokes shimmering ocean waves. Completely enveloping the viewer, the foggy pink room appears to be related to works by the LA Light and Space artists, although Janssens seems to have claimed a territory all her own.

Installation view, Larry Poons, “Choral Fantasy,” 2016.

Photo Courtesy Loretta Howard Gallery.

5. Larry Poons at Loretta Howard Gallery, through February 13.

Patti Smith referred to Larry Poons as “our cowboy Monet” in a 1970s New York magazine article. She was alluding to his reputation as a master colorist, as well as an adventurous art-world renegade. Poons was producing at the time the so-called vertical drips series of paintings, which are featured in this dazzling show, “Choral Fantasy: Paintings from the 1970s to 1980s,” titled after a Beethoven composition. Each of the dozen mural-size paintings on view, many never before shown, indeed conjure a grand symphony of fluid rhythms and pulsating beats.

Poons’s early art-world recognition in the 1960s came from a series of abstract paintings of hard-edge dots and lozenge shapes set against backgrounds of contrasting colors. The works set in place a flickering effect that is arresting and mesmerizing. Poons abandoned the technique after only a few years, when his work was too often associated with Op Art. He fearlessly changed his approach in new and ongoing explorations of color, light, and movement. The artist’s career has long been one of high drama, and sometimes misunderstood by critics and the public, so this tightly-focused exhibition is art-historically significant, aside from being a rare, sumptuous treat.

Like cascading waterfalls of color, the “vertical drips” series, built upon Pollock’s example and Morris Louis’s endeavor, influenced a host of younger painters, including Pat Steir and John Armleder. In the works in “Choral Fantasy,” Poons elicits another kind of hypnotic optical effect. Spend some time with paintings such as Spanish Dancer and Wiseman (both 1975); it may take a full minute or two for the effect to take hold. The eye cannot alight upon any one area of the canvas. Instead, it is obliged to follow an endless, up and down, high-speed vertical line of vision—in metaphorical or transcendental terms, the line from earth to heaven, and back again. As a champion motorcyclist, now, at 78, in the senior division, Poons pictorial references have to do with the ever-shifting landscape.

Bradley McCallum, Nationalist —Slobodan Milošević Diptych (International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, February 12, 2002 appearance, after a photo by Raphael Gaillarde; died in custody, trial terminated), 2015.

Photo courtest Robert Blumenthal Gallery.

6. Bradley McCallum at Robert Blumenthal gallery, through March 5.

For years, Bradley McCullum, often working in collaboration with artist Jacqueline Tarry, has directed his artistic pursuits to sculptures, installations, paintings and performances with a political edge, and social significance, which are apparent in the ten recent works on view in this solo exhibition. The meticulously executed oil paintings, including large, photorealist-style portraits of notorious war criminals, explore masculine configurations of power, in war, international relations, and militarism. It is a potent and thought-provoking show with far-reaching implications, especially in this presidential election year, with all of its attendant angst, drama, and conflict.

The oil studies of tyrants, such as Thomas Lubanga Dyilo, of the Democratic Republic of the Congo; and Cambodia’s notorious Nuon Chea, of the Khmer Rouge; and Serbia’s Slobodan Milošević, have a kind of jarring and palpable intensity, especially as McCallum paints each in “reversal” or negative image, which resembles a ghostly X-ray. Despite the harrowing subject matter, McCallum is hypersensitive to formal elements in the works, which can often appear elegant and restrained, as in a series of refined oval compositions of painted silk. These lively and colorful pieces feature artfully abstracted images of various violent demonstrations around the world, among them anti-US protests that inevitably include burning of the American flag.

Stephen Dean, Crossword, 2015.

Photo Courtesy Ameringer McEnery Yohe.

7. Stephen Dean at Ameringer/McEnery/Yohe, through February 6.

Labor intensive doesn’t begin to describe the technique New York-based artist Stephen Dean uses to create the large-scale “Crossword” watercolor compositions featured in this exhibition of recent works. Each square of the hundreds of crossword puzzles from newspapers and magazines, mounted on archival Tycore, is tinted with a drop of watercolor, estimated at 100,000 drops per panel. The process of creating these works must be as rigorous and contemplative as the resulting images, which are at once visually arresting and psychically soothing. The fluid color counters the rigid geometric patterns of the crossword sections in each work, instigating a luminous, pulsating surface. The overall feeling must certainly correspond to that of finishing a particularly complex puzzle.

A rear gallery features “You are Here,” a series of three-dimensional paper works, featuring overlapping grids meticulously drawn in red ink on translucent sheets of Chinese calligraphy paper or rice paper. Intersections of the drawn lines are pinpointed by colorful glass-head needles that protrude an inch or so from the surfaces. The structural integrity and meditative comportment of these unusual hybrid sculpture-drawings, is a forceful addition to Dean’s by-now formidable oeuvre, which consistently centers on the phenomenological properties and sociological implications of light and color.

Mike Bidlo, NOT Duchamp, Flattened Bottle Rack, 2016.

Photo courtesy Francis M. Naumann Fine Art.

8. Mike Bildo at Francis M. Naumann Fine Art, through February 26.

I think of Mike Bidlo as the purist of the so-called appropriation artists. He is never content to merely mimic the works of earlier masters, as his peers Sherrie Levine or Richard Prince might do. For each endeavor, Bidlo did extensive research in his subjects, and in some ways sought to embody the artist whose works he wished to appropriate. The results of his efforts, while astonishingly convincing mirrors of the originals, are also inevitably imbued with the artist’s own unique life force. Never wishing to make “fakes,” he clearly titled each series NOT Picasso, NOT Brancusi, NOT Pollock, etc.

For “Mike Bidlo: NOT Duchamp: Fountain and Bottle Rack,” his first New York solo in a decade, the New York-based artist takes on the Dada maestro. He recreates in series two of Duchamp’s most famous—or infamous—works, Bottle Rack (1914), and Fountain (1917). Admirably, Bidlo applies his own anti-art gestures to these pieces. He smashed a meticulously crafted ceramic model of Duchamp’s scandalous urinal, reconstructed it, and eventually cast it in a bronze edition, several examples of which appear in the show. The most hilarious and poignant of all are Bidlo’s “bottle racks.” He crushed several of the homely bottle racks with a steamroller (in the web, you can see a video of Bidlo orchestrating this aggressive act). All of Bidlo’s bottle racks got plated in shiny chrome. The crushed ones appear in the show as striking wall reliefs—glimmering formalist abstract sculptures, now far removed from their once lowly function.

Martha Tuttle, Clear Sound (3), 2015.

Photo courtesy Tilton Gallery.

9. Martha Tuttle at Tilton, through February 20.

Understated and graceful, Martha Tuttle’s “Metaxu” is an impressive solo debut. The recent abstract, wall-relief assemblage pieces here are made with numerous layers of silk, wool, paper, and unusual materials like hematite, woad, indigo, and logwood. The rectangular shaped textiles, which she weaves herself, are the primary components of representative works, such as Clear Sound (3). The material richness of the surface here counters the overall look of the piece, which is informal, or even abject. It features rough-hewn layering of muted gray tones in a spare composition of mostly rectangular shapes.

One of the best works on view, Grasses is a particularly large and resplendent composition, 60 by 67 inches, with a irregular square piece of pale blue-green cloth overlaying the deeper blue tones of cloth and paper visible along the sides and underneath. Tuttle’s work bears favorable comparison to the work of her father, Richard Tuttle, in its inventive use of materials and seemingly off-the-cuff attitude. Perhaps more painterly in approach, and a bit more sober in tone, the works in this show demonstrate that Martha Tuttle has developed a vision and a means of art-making that is entirely her own.

Jeff Gabel, installation view.

Photo courtesy of the artist and Spencer Brownstone Gallery.

10. Jeff Gabel at Spencer Brownstone, through February 27.

Portland, Oregon-born, New York-based artist Jeff Gabel has reached middle age and isn’t taking it lying down; he goes public with it in this show, “28,000 pages, or ‘In Color,’ a mid-life crisis.” In an on-going performance during the course of the exhibition, the artist is in the process of covering all the walls of the gallery with a frantic narrative of his own improvised design, including captioned figurative drawings in colored pencil that could be the ranting of a mad man, were the audience not clued in to the source of the mayhem—a 48-year-old artist in crisis.

Near the center of the room, a white sculpture stand is piled high with books, including Keith Richard’s autobiography, A Life; Tender is the Night by F. Scott Fitzgerald; and Albert Camus’s The Plague. These are just selections from the 28,000 pages that Gabel purportedly has read over the past year. The artist, as an avid reader still, suggests an optimistic attitude that you can, in fact, teach an old dog new tricks.

David Ebony is a contributing editor of Art in America and a longtime contributor to artnet.