Welcome to the Art Angle, a podcast from Artnet News that delves into the places where the art world meets the real world, bringing each week’s biggest story down to earth. Join us every week for an in-depth look at what matters most in museums, the art market, and much more, with input from our own writers and editors, as well as artists, curators, and other top experts in the field.

This April, after a punishing two years apart during the pandemic, the international art community will gather together on the magical, watery isles of Venice for its periodic ritual assessment of what the world’s finest artists have been thinking about and making to grapple with our changing world.

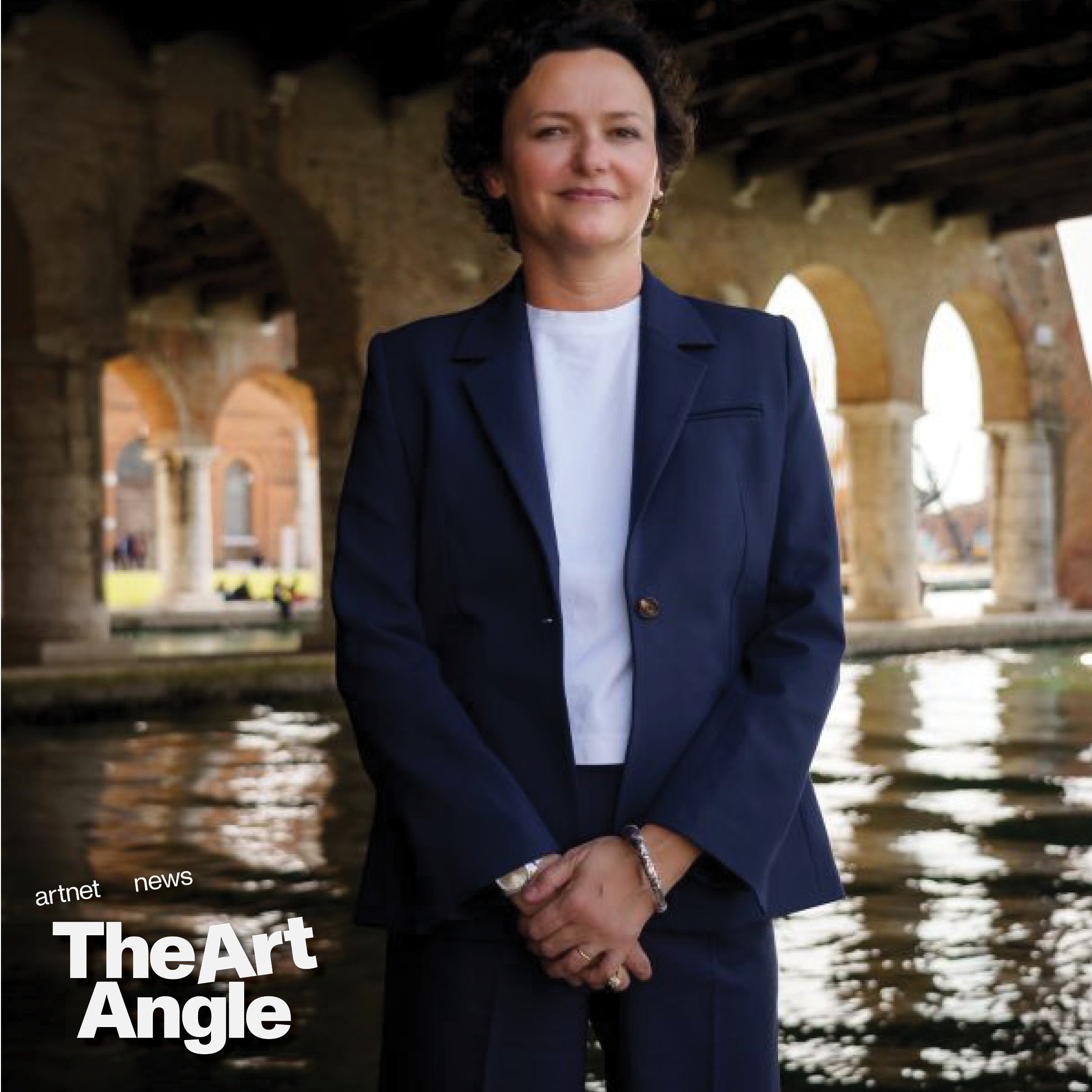

They call this climactic event the Venice Biennale, and each time it has been presided over by a visionary figure whose role it has been to transmute the work of all these artists into a coherent statement about our time. This year, that exalted figure is named Cecilia Alemani. In the Biennale’s 127-year history, Alemani is the fifth woman to curate the show. In 2017, she curated the Italian pavilion—the largest national pavilion on site—which she said gave her a “definite advantage.”

Ultimately, the Venice Biennale is just a big exhibition, and Alemani is a professional curator, whose day job is curating art for New York’s High Line. But the show always has an aura of the religious about it, granting mere mortals the opportunity to commune with the biggest and best ideas floating around the globe. And this time around, the globe is in rare and urgent need of big ideas, with existential crises raging all around us, demanding reckoning.

In this week’s interview, Alemani Zooms in from her apartment in Venice, smack between the Arsenale and the Giardini, as art handlers and artists race around installing large works and finalizing pavilion presentations. For Alemani, the IRL action is a welcome change from two years in isolation, as she has worked to forge an exhibition as the world faltered around her.

“Because the entire process of my show has been done through the mediation of the screen, the show is actually quite the opposite,” Alemani said. “It’s extremely materially concrete.”

Titled “The Milk of Dreams” after a book by Surrealist artist and author Leonora Carrington, which the curator describes as “very simple, very joyful, but also quite macabre,” the exhibition suggests a fitting bit of symmetry with our own moment: the Surrealist movement emerged in 1924 just after the end of World War I, in part as a reaction against totalitarianism and militarization.

In addition to the horrific invasion of Ukraine by Russian forces in February, “If you think about the past six years with Trump and everything that has been happening,” Alemani noted, “you could say there is a sort of parallel between the two historical moments.”

This week, we’re thrilled to welcome Alemani on the Art Angle, where she spoke with Artnet News’s Editor-in-Chief, Andrew Goldstein, about the struggle to curate a show via Zoom and what she has in store for us all in Venice.

Listen to other episodes:

‘Assimilating Is Very Dehumanizing’: How Afghanistan’s Artists Are Making Their Way in Exile

‘Visibility Means Survival’: How the Art World in Ukraine’s Besieged Capital Is Fighting Back

The Art Angle Podcast: Marina Abramović on How Her Artistic Method Can Change Your Life

The Art Angle Podcast: Jennie C. Jones on Why You Should Listen to Her Paintings

The Art Angle Podcast: The Black Art Visionary Who Secretly Built the Morgan Library

The Art Angle Podcast: How Lucy Lippard and a Band of Artists Fought U.S. Imperialism

The Art Angle Podcast: Art, Lies, and Instagram: How Catfishing ‘Collectors’ Duped the Art World

The Art Angle Podcast: The Nazis Stole Her Family’s Art. Here’s How She Got It Back