The scaffolding is down, the dust has settled, and after a six-year expansion project led by Diller Scofidio + Renfro, the Museum of Modern Art has been reborn. The $450 million undertaking has increased the preeminent institution’s exhibition space by nearly a third, adding warrens of vast, austere new galleries, a performance “studio” in the museum’s center, and enough other changes that longtime MoMA visitors in particular will find themselves grasping for a sense of orientation. Looking at the map of the new fifth floor, where the canonical modern-art galleries reside, it’s as if your favorite golf course had suddenly added another nine holes. If only MoMA had golf carts, too.

But while the architectural changes are bracing, the most dramatic transformation has occurred within the galleries themselves, where the curatorial staff has accompanied the expansion with a rehabilitation project, of sorts—a noble attempt to correct lacunae in the collection displays that failed to reflect the truly diverse (i.e., not just white-and-male-and-Eurocentric) nature of the past century and a half of art. As a result, all of the art has been re-contextualized, with the masterworks gaining eye-opening new neighbors, and gallery displays adopting a 360-degree view of a subject across mediums—a big change from before, when each department was more or less kept separate. If you think of the museum as one big party, it’s become a much more interesting party. There are plenty of intriguing strangers to meet and acquaintances to get to know better. There are new people to talk to, in other words, and the conversation is livelier than ever.

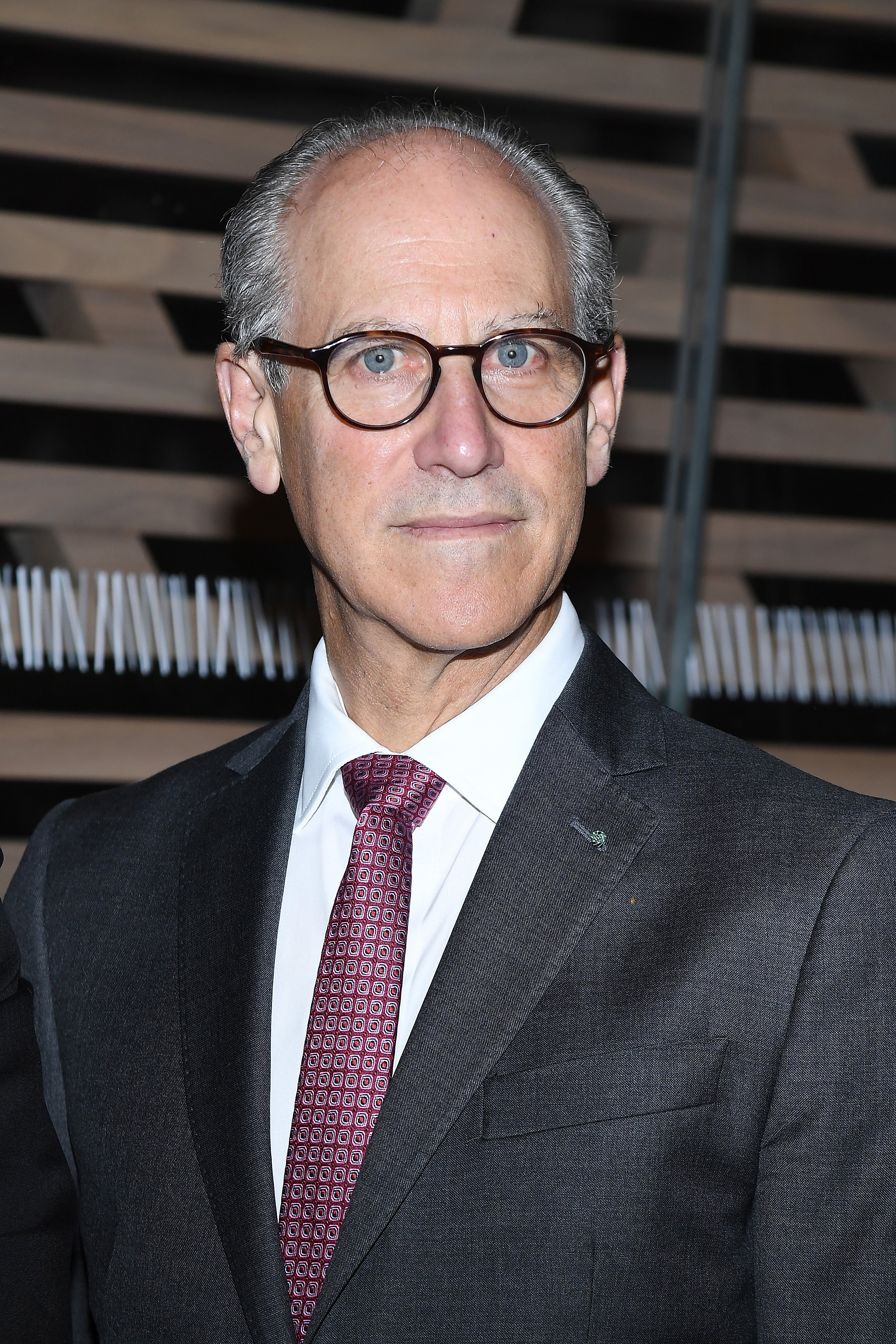

So, should we think of this new iteration of the museum as woke MoMA (or WoKE MoMA)? Not quite. As MoMA director Glenn Lowry explains, the curators found it impossible, or impractical, to try to correct every previous oversight in one go—which is why the museum’s collection displays will remain in flux, revolving out in regular intervals to be refreshed with new twists on the historical narrative.To find out more about what it means to remake the Museum of Modern Art, and where things go from here, artnet News’s Andrew Goldstein sat down with Lowry in his spacious office—tucked away in the labyrinth of offices, noticeably untouched by the renovation—to talk about MoMA’s newest chapter.

Exterior view of The Museum of Modern Art, 53rd Street Entrance Canopy. The Museum of Modern Art Renovation and Expansion Designed by Diller Scofidio + Renfro in collaboration with Gensler. Photography by Iwan Baan, Courtesy of MoMA .

The reopening of the museum this month represents a deep rethinking of MoMA’s collection, and, by extension, of the history of art for the past century and a half. What does “Modernism” mean to MoMA today, and is it still capitalized?

That’s a great question. I wouldn’t capitalize it, but it still means a foundational idea that we are committed to exploring. What has been interesting, over the last decade as we delved deeply into what we wanted to achieve in this iteration of the museum, was a recognition that one of the foundational ideas behind the museum was that it would be a work in progress—that it wasn’t actually finished, it was evolving and changing and developing over time.

I’m inspired by that, and I think our curators were deeply inspired by this notion that the definitions that had begun to accrue around a narrow reading of modernism or modern art could be expanded productively to embrace a much broader and more generous understanding of the concept, and a recognition that there were many different modernities that evolved over time in different places, and that they talked to each other. They weren’t independent and isolated conversations.

As we looked at this carefully and started interrogating what we wanted to do, it became very clear that, actually, when you go back into our history, our collection, and the exhibitions we did over the last almost 90 years, there are many, many instances where there was a deep interest in what was going on elsewhere in the world. And the collection itself is much richer and broader than came to be seen through its display.

What I took away from that is that over time, we had become two museums: a museum that was on display, which was refined and carefully focused on iconic works of European and North American art, by and large; and a museum in storage that was much larger, more varied, more complicated, and that included great works by artists from many different regions.

These artists were clearly of interest to curators at one moment; that’s why they were acquired. But now, many years later, they had been either forgotten or overlooked. By committing ourselves to going back and exploring what was already there, we found so many lineages to build on. It’s been an extraordinary journey.

It’s a tribute to the extraordinary scope of MoMA’s collection that, now that there’s an impulse towards the rediscovery of overlooked artists, all you have to do is rummage around the attic to be able to say, “Hey, we’ve got those people, too.”

Well, to be fair, the curators also added enormously to the collection. Over the last decade we have dramatically expanded the number of objects in our collection. And, even more importantly, we have expanded who’s represented in the collection. So we’ve made a really significant commitment to ensuring that we focus on women as much as we have focused on men; on collectives as much as on individuals; on artists working in different geographies as much as those in Europe and North America. So, yes, the kernel for that was already in the collection, but we were able to expand it.

For instance, now we have our first curator whose focus is on contemporary art from Africa, because we were able to get this core group of works of contemporary African art through a gift from Jean Pigozzi. We now have two curators whose field is Latin American art, building on this extraordinary gift of Latin American art from Patty Cisneros, as well as acquisitions we have made. So it’s a combination of what was there with a lot of new friends and voices.

Pablo Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon on the left, and Faith Ringgold’s American People Series #20. Image: Ben Davis.

In addition to the wealth of new perspectives, there are also some moments in the rehang that will be powerful and unexpected for longtime MoMA devotees and new visitors alike—most prominently, the decision to display Les Demoiselles d’Avignon next to Faith Ringgold’s painting of a bloody race riot. What do you hope the viewer will think, other than, “Whoa”?

I’ve been thinking about that, of course. So, first we want people to stop, and realize what a frightening, difficult painting the Demoiselles d’Avignon really is. One hundred years on, it’s iconic, and to some extent we take it for granted.

I think the the introduction of Ringgold—and also Louise Bourgeois [whose sculpture Quarantania, I (1947–53) is also in the gallery]—into this conversation recenters this painting. Picasso, when he was painting it, wasn’t thinking about formal problems like Cubism, even though the painting is often seen as an essential moment in the evolution and development of Cubism. He was thinking about the power of African art. He was thinking about the ways in which this brothel operated. He was looking at the kind of fraught, tense nature of these women who populate the painting. So I think this installation acknowledges all of the important formal dimensions that Picasso represented, but it also says: there are other readings, too.

And Ringgold, who spent a lot of time at this museum looking at the Demoiselles d’Avignon, and looking at Guernica when it was here, absorbing the lessons of Picasso—she’s in conversation with him. She is engaging him. Obviously she deals with a whole other set of issues as well, around race and the fraught politics of the ’60s. But I think linking them together creates a different way to see Picasso.

The other day I was in the galleries with Philippe de Montebello, the legendary director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and somebody who I admire a lot, and who has always been incredibly thoughtful and generous to me and to this institution. And he looked at the Ringgold and said, “Great painting. You know, she painted my portrait 15 years ago.” So for him, it wasn’t so jarring. He understood who she was, and what she was doing.

Henri Matiesse, The Red Studio (1911) and Alma Thomas, Fiery Sunset (1973). Image: Ben Davis.

The other thing that is interesting, of course, is that everyone who comes to MoMA to see the great Demoiselles d’Avignon, arguably the most essential textbook example of modernism, will also perforce, and in an arresting manner, encounter this 89-year-old African American artist who lives just a mile or so north of the museum, in Harlem. That’s a powerful way to flex the museum’s muscles in terms of directing viewer’s attention and educating an audience.

Although I think the more radical move is actually in the previous gallery, where we introduce film and photography as utterly foundational to any reading of the 20th century. Before, the museum had this march from Post-Impressionism to Cubism to Abstract Expressionism to Pop art to so on. It felt like it was an inevitable march of progress, and it was all about painting and sculpture. With the introduction of film and photography, which are the radical media of the 20th century, it changes the whole narrative at the museum.

So, in a way, Ringgold is a painter, and she’s fighting with all the demons and ghosts of other painters. But, in fact, early 20th-century artists were fascinated by photography. They were fighting with that, but they were using it. You know, the great Cèzanne Bather, which is often considered one of the iconic, foundational paintings of the Museum of Modern Art, wasn’t painted from a live subject—it was painted from a studio photograph. So right at the outset, even at the end of the 19th century, photography is being deployed for many different uses, including by artists.

Paul Cézanne, Château Noir (1903-04) , and Paul Cézanne, The Bather (ca. 1885). Image: Ben Davis.

Since you embarked on this project in the middle of 2013, our world has undergone some extraordinary changes: Trump and the rise of populist nationalism, the #MeToo movement, a piercing awareness of climate change, a powerful rejection of colonialism’s trappings, and ever more digitization. How have these pressures shaped the new museum?

They certainly were present in the way we were thinking. Like artists, like everyone, we live in the real world. We’re surrounded by the debates and controversies and critical issues of the moment. I think there was a real effort on the part of the curatorial teams that worked on these installations to be attentive to issues around gender, around race, around climate change, around immigration, and, for sure, the fraught politics not just of the current moment, but of the last century.

The 20th century was a very brutal century, rolling back to the First World War, followed by the Second World War, followed by the Korean War and the Vietnam War, followed by the events of 1989. We’ve lived in turbulent and difficult times, and that’s reflected in many of the works of art that are on display. This is to say, all of these forces are present to a lesser or greater degree, depending on the works of art we had in our collection that could make those issues manifest.

More recently, there’s been this phenomenon where people are not just grappling with the issues themselves—of race, of gender, et cetera—but also paying close attention to how others are grappling with them, and judging them as a result. In reopening the museum, was there any trepidation in terms of, “Are we leaving anyone out? Is there somebody who might see this as problematic?”

Well, I’m not quite sure how to respond to that beyond saying that anytime you do an exhibition—and it doesn’t matter what scale it is, whether it’s a single gallery or a whole museum—you recognize that it’s only a partial view of something. You can never be comprehensive in some absolute way. So, in a way, we’ve gone in the opposite direction and decided we’re not even going to attempt to do that. Instead, we are going to engage again and again and again.

The way we are looking at it is that, rather than thinking of this display—which sprawls across almost 170,000 square feet and consists of almost 2,500 works of art—as somehow permanent or even quasi-permanent, we think of it as a point in time that over a two-to-three-year period will virtually entirely change again. Critical works that people travel long distances to see, like Matisse’s Dance, Van Gogh’s Starry Night, the Demoiselles d’Avignon, Monet’s Water Lilies—we’re not going to change those. But we might change where they’re located, and we certainly will change their neighbors.

The “New Expressionism in Germany and Austria” galleries. Image: Ben Davis.

The gallery that you mentioned with Faith Ringgold? In just over a year, it will be a completely different installation. And we want to do that for multiple reasons. One, we have all of these extraordinary works of art in our collection and we want to bring them out, to put them in conversation. And even more importantly, we know that there are dozens of issues that were left on the table when we made hard decisions about what to show in the museum. We want to come back to those issues.

We did literally hundreds of storyboards about potential installations, because the other thing we’ve done is move away from thinking that our galleries are purely sequential. Now, each gallery is a self-contained unit linked only by broad chronology, so you can pull one of those units out and put another unit in and it’s like substituting one chapter with a different chapter.

In other words, they’re modular.

For us that’s very important, because we weren’t able to address some of the urgent issues that you mentioned. We’ll be able to address them the next time around.