Opinion

An Art Critic’s Picks: 10 New York Artworks to Lift Your Spirits

In a time of grief and uncertainty, here's the art that I go to in search of comfort and perspective.

Like many people in the art world, I’m in deep worry—almost mourning—at the election of Donald Trump. He seems to stand for values at odds with almost everything I believe in, and that art represents. Eventually, I’ll be ready to fight for a future without him, but for now, I’m almost too sad and anxious to leave the house. The one place I can reliably find solace, for most ills that ail me, is in art.

Here are some works I’ll hope to get to over coming days, to soothe my troubled soul.

Buddha Pakistan, Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa province, possibly Takht-i-bahi monastery, ancient region of Gandhara 3rd century, on view in Gallery 235 of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

I’d like to think that, with enough staring at this image of Buddha, I might achieve a wise remove from all earthly troubles. But I doubt it. The truth is, I head to his corner of the Met because it’s almost certain to be nearly empty. The quiet alone is soothing to an unquiet soul.

Also, although I’m far from expert in such things, this particular statue seems to bear traces of Greek art, from Alexander the Great’s brief incursion into the Indian subcontinent. I’d like to think it stands for the virtues of cultural mixing that Trump’s America First jingoism is so loath to admit.

***

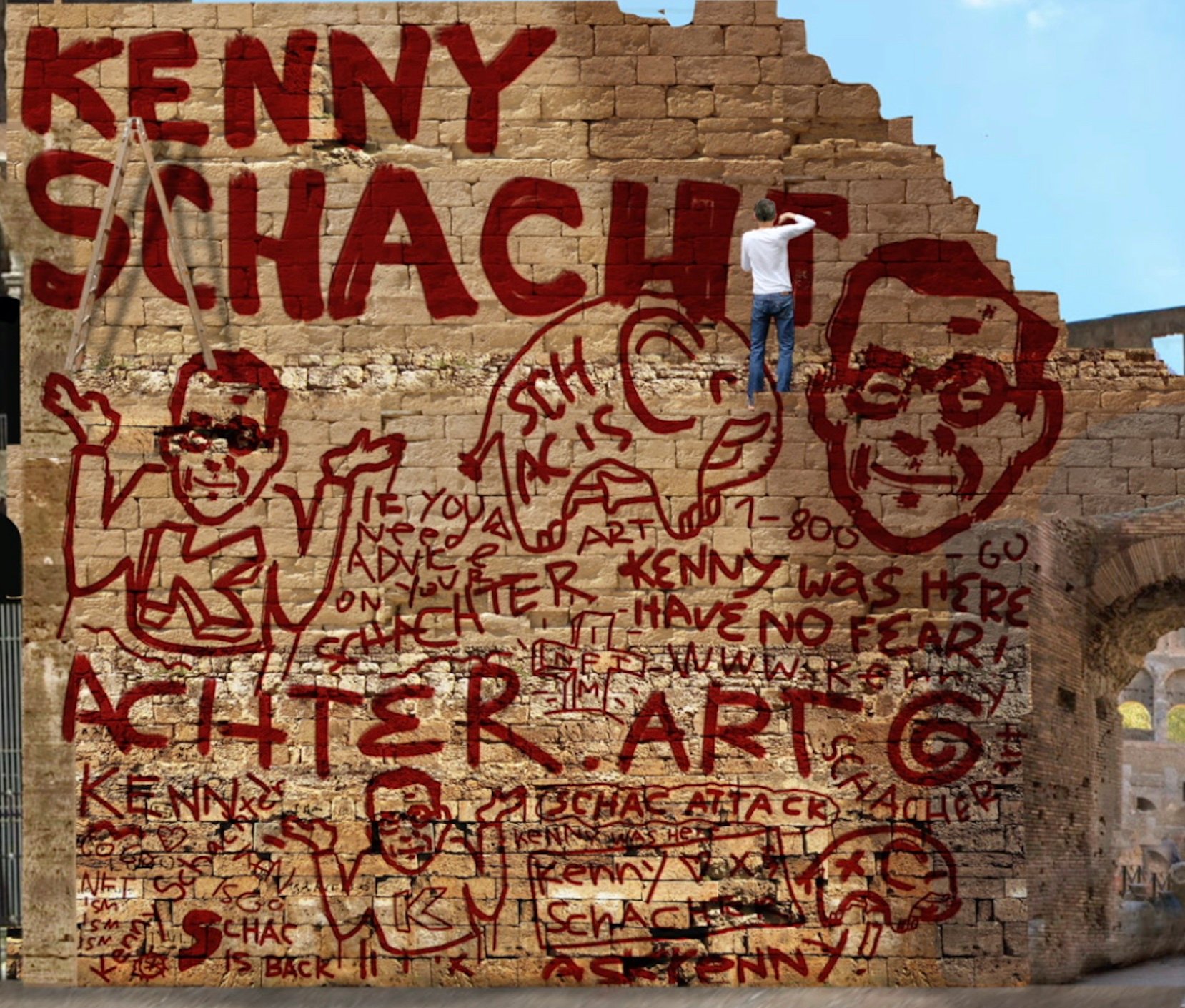

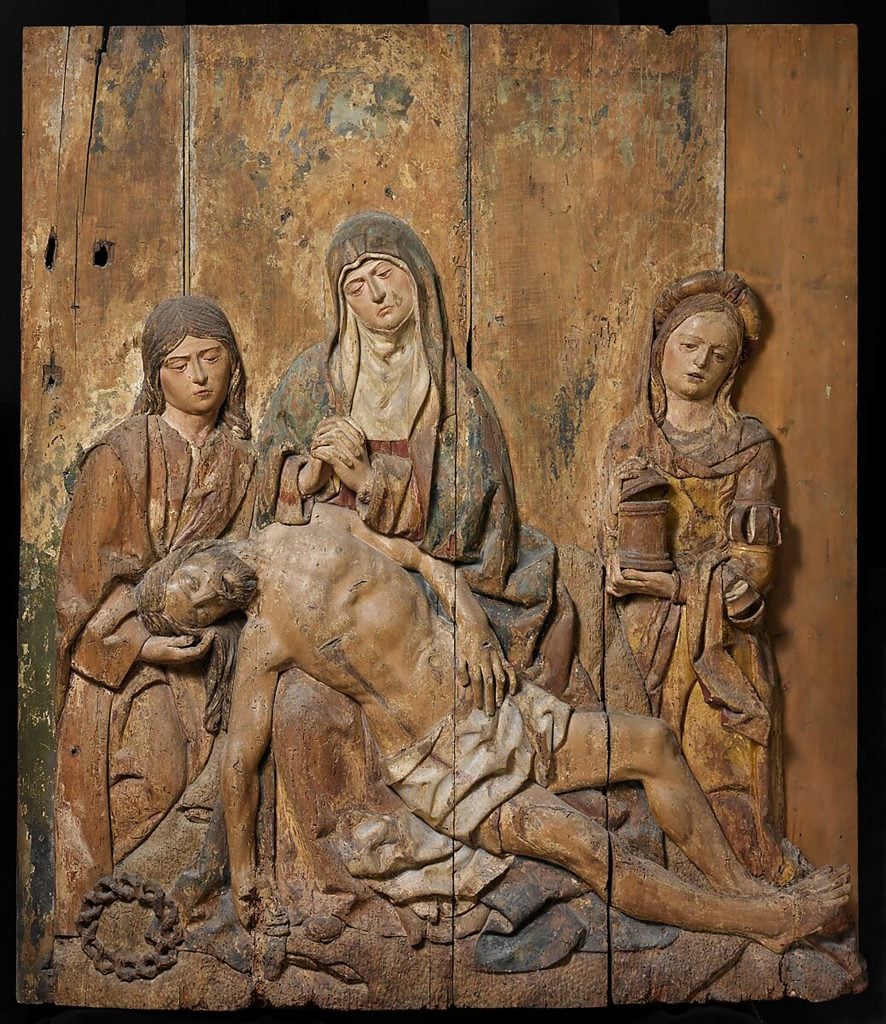

Pieta, French, early 16th century, on view in gallery 306 of The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

I often find relief from sadness by wallowing in artful depictions of grief. That’s a peculiar, somehow illogical tendency that I happen to share with a lot of people. Country music depends on it.

As the most devout and observant of atheists (I never fail not to go to church on Sunday), I’m not touched by the particular beliefs inscribed in a scene like this Pieta, but the emotions it captures help me endure mine.

***

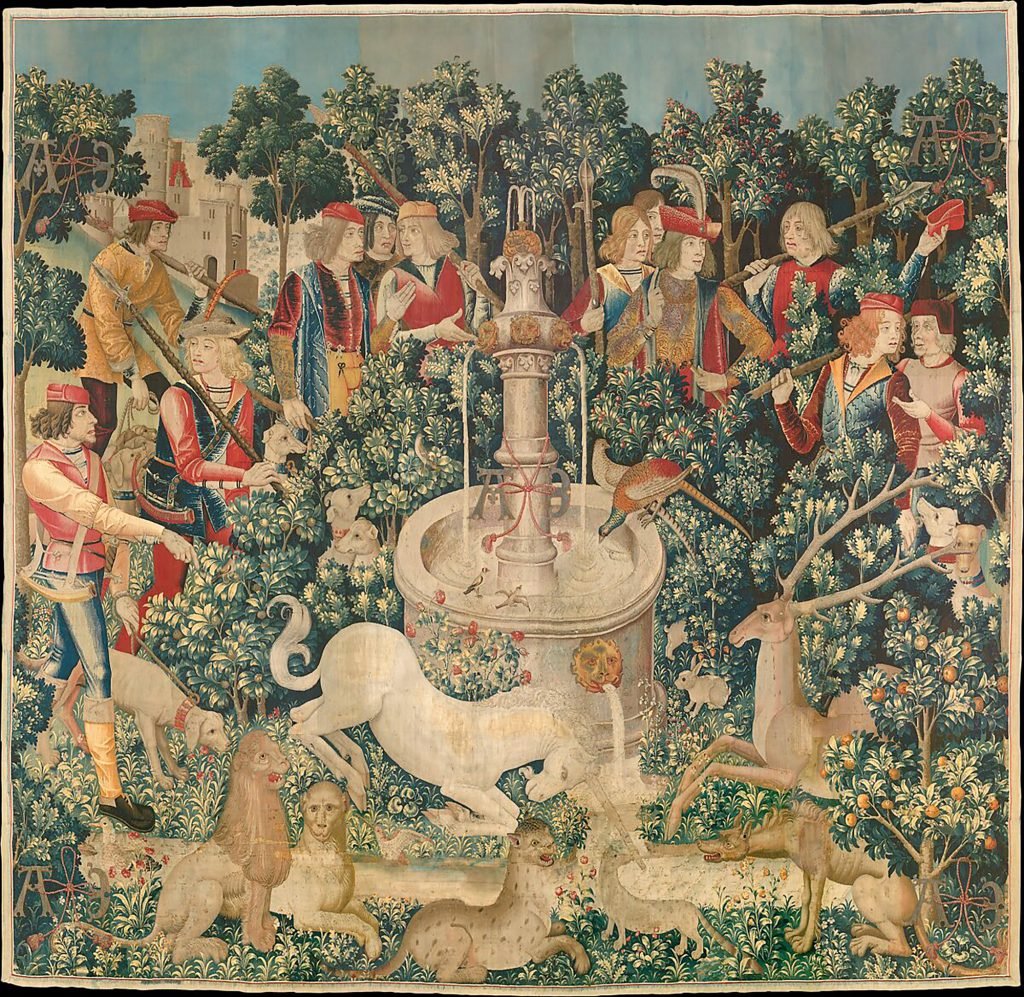

The Unicorn Purifies Water (from The Unicorn Tapestries) French (cartoon)/South Netherlandish (woven) 1495–1505, on view at The Met Cloisters. Photo: The Metropolitan Museum of Art

My favorite escape has always been to the Middle Ages—I wore a knight’s tunic and hose for much of my childhood—so the medieval art at the Met’s Cloisters branch is my obvious refuge from trouble. Surrounded by the panels of the Unicorn Tapestries, I can almost imagine I’m a million miles, and five centuries, away from this week’s election.

Funny thing is, I’m pretty sure the knights in shining armor who paid for these tapestries sought escape to a medieval fantasy that wasn’t so different from mine. Drowning in mud and plague and endless warfare, they needed it even more than I do, today. That makes me feel a bit better.

***

On The High Line: Glenn Ligon, Untitled (America/Me), 2022/2024. Photo: Timothy Schenck, Courtesy of The High Line

Glenn Ligon’s “America” series of neon pieces has always been a favorite of mine, for painting an almost perfect portrait of this troubled nation. Its latest iteration, on a billboard in Chelsea just off the High Line park, strikes me as the series’ culmination: By crossing out the two A’s and the R, I and C, Glenn gets at what’s left: A Trumpian “ME.”

***

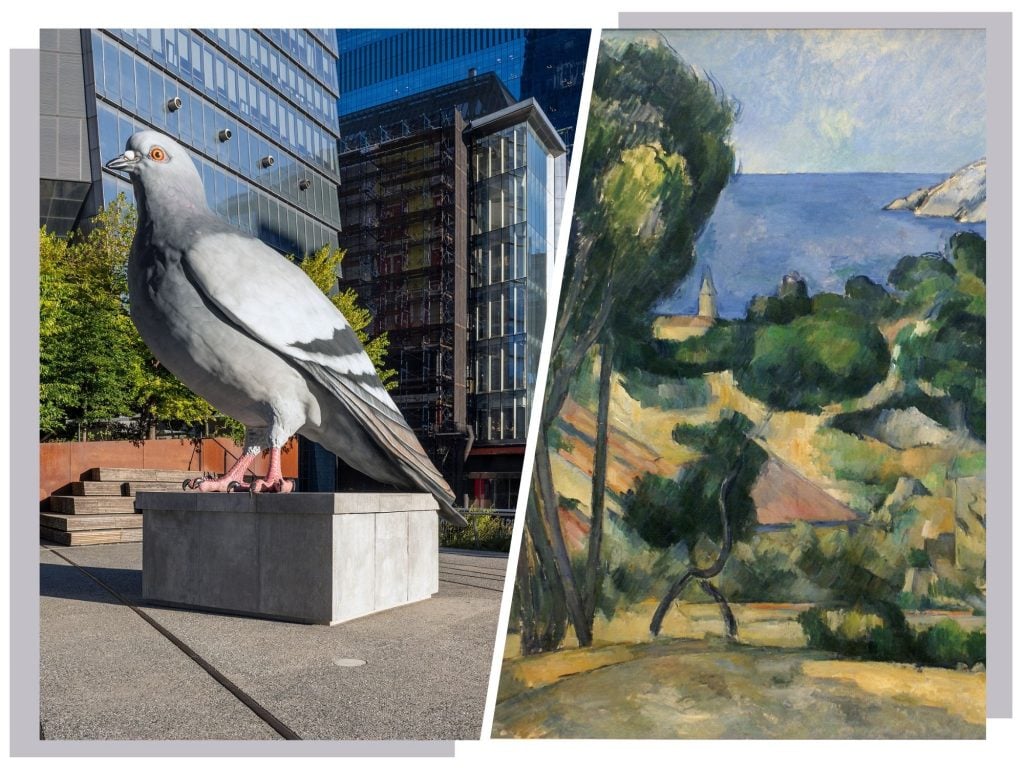

On The High Line: Iván Argote, Dinosaur, 2024. A High Line Plinth commission. Photo: Timothy Schenck

I’ve been wondering, over the last day or two, if the world’s current trend towards autocracy has its roots in some deep, animal, species-wide intuition that we’ve fouled our nest to the point of no return, and now we’ve gone rabid at the prospect. I get genuine solace from thinking that the mess we’ve made, and our madness, really won’t matter to the planet as a whole. Humans will never be more than a blip in its history—more short-lived, by far, than the dinosaurs whose direct, living descendent is captured in Iván Argote’s huge sculpture on the High Line.

I know no more imperturbable creature than a pigeon. This one’s an example to us all. She knows her kind will outlast us.

***

Agnes Martin, Harbor Number 1, 1957. Photo: ©2024 Agnes Martin via MoMA

I can’t say the works so often cited as “meditative” or “contemplative” —Rothkos and Morandis, etcetera—normally help me to contemplate or meditate, much. They tend to get me thinking and talking and writing, instead. But in this moment of desperation, I’m willing to give them a try. Gallery 516 at MoMA has a nice selection of classic Agnes Martins, with the peaceable horizontals and grids that many people find deeply soothing. I’m rather more drawn to the dynamic tensions of an atypical early work like Harbor Number 1. There’s less to talk about in it.

Chapel of the Good Shepherd at Saint Peter’s Church, New York, NY, 1977. Photo: Marco Anelli, 2023

Sometimes—as in, “now”—you want a place where contemplation is even more mandatory than in a museum. Such a place is Louise Nevelson’s Chapel of the Good Shepherd at Saint Peter’s modernist church on Lexington Avenue, a building almost swallowed up, since 1977, by the old Citicorp Center skyscraper. Saint Peter’s is a Lutheran church, and Nevelson was a Jew, so I figure there’s room for an atheist art lover somewhere in between.

I haven’t been to Nevelson’s chapel for ages, but for a while now I’ve been saying that Nevelson, once a giant art-star, is due for some serious rediscovery. This seems a fine moment to do the rediscovering, with her chapel a fine and public place to start. My mood could hardly be darker, so I want to bathe in the shifting light of its whites.

***

Walter De Maria, The New York Earth Room, 1977. Photo: ©The Estate of Walter De Maria. Photo-John Cliett, Courtesy Dia Art Foundation

The same year that Nevelson made her chapel, Walter de Maria made a space that feels even more sacred in its silence. For his New York Earth Room, de Maria spread 280,000 pounds of good black earth across all 3,600 feet of a Soho loft, filling the space to about knee-high on a tall man. The heft of the pile is palpable, and just a touch ominous. It seems to brood, as though not quite fulfilled in its lack of crop. Its endless waiting makes our rush—and maybe our worries—seem all the more inconsequential. I’m happy to imagine my own worries, about Trump, as less consequential than they feel.

***

Richard Serra’s Every Which Way (2015) at David Zwirner. Photo: Kenneth Bachor/Artnet

Sometimes, a somber, heavy mood requires somber, heavy art. Misery seeks company. Richard Serra’s Every Which Way, a 2015 installation just now opening at David Zwirner’s gallery in Chelsea, is described as a kind of labyrinth of sixteen steel panels, each six feet wide, twelve inches thick, and as much as eleven feet tall. I plan to get lost inside, and pout.

***

Cezanne’s L’Estaque on view at MoMA.

For me, a great landscape by Cézanne, like this one at MoMA, is as good as Western art gets. It is completely gripping but absolutely ungraspable. I’ve never read an elevator pitch on Cézanne that could even start to sum him up. Ditto for any massive tome. Cézanne doesn’t offer answers. He gets us asking endless questions—about the world, and pictures, and ourselves—and that’s the very purpose and definition of art.

It’s the remedy for Trumpish certitude.