A 39-year-old producer and an octogenarian art historian have teamed up to create a digital masterclass about an artist who died more than 500 years ago.

In many ways, Waqas Ahmed and Martin Kemp—producer and instructor, respectively, of the masterclass on Leonardo da Vinci—share the sort of omnivorous intellectual appetite that qualifies them, like their subject, as “Renaissance men.” Ahmed, who has a background in neuroscience and diplomatic publishing, directed Nasser Khalili’s art collections. He interviewed Kemp, the Oxford University art history professor emeritus and Leonardo expert, in 2016 for his book The Polymath. They stayed in touch and, in 2019, began sketching out a plan for the masterclass.

Much ink has spilled on Leonardo’s life and work, but there had yet to be a digital educational course, Ahmed told Artnet News in a video interview from the U.K. Most importantly, he wanted to offer attendees a sense of what they could take away today from Leonardo. Kemp was initially skeptical.

“As a historian, you don’t want to say, ‘Well, we are only looking at this person, because he has lessons to teach us,’” he said. But convinced Leonardo remains very relevant today, Kemp changed his mind. “It’s one reason why he’s got such a grip on people’s imagination—whether they’re engineers, medics, fans of art, or whatever,” the historian said.

Kemp, who typically lectures without notes, found the medium conducive, and Ahmed dubbed the scholar, who rarely needed retakes, Al Pacino-like. After viewing the six classes, which run about four hours over 22 sessions, we found that the masterclass illuminated both Leonardo’s and Kemp’s ways of thinking.

Toward the end of the course, Kemp describes seeing Leonardo’s masterpiece, Mona Lisa, out of its frame—which he has done twice—as “spine-tingling.” He told Artnet News it was tense at first, when the painting came out of its bullet-proof glass and frame, and was set up on an easel. He worried the picture he had studied for so long would disappoint. It did not.

“There is a sense of something happening between the picture and yourself. This sounds entirely pretentious, but it does happen. Rembrandt can do it with portraiture. Bernini can do it in marble for heaven’s sake,” he said. “The picture becomes a kind-of living thing.” Trying to describe the experience makes it “dry and dusty,” he added.

Kemp was one of the scholars to authenticate Salvator Mundi as the Renaissance master’s hand. In the masterclass, he wades carefully into politics and religion as he discusses that attribution, which builds upon “more years than I’m going to confess” studying Da Vinci, he says. “I keep thinking I’ve finished, but I have never finished.”

Here are five takeaways we found after completing the masterclass.

Leonardo made mistakes

One of history’s greatest minds aimed so high that da Vinci, it turns out, was rather error prone.

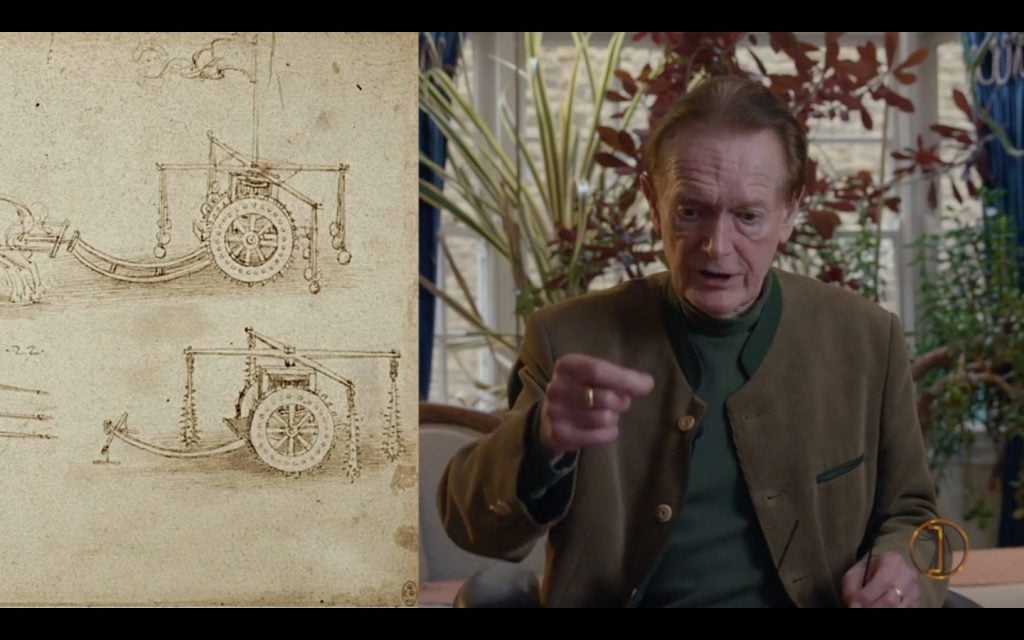

He drew the gears incorrectly in what is often mistakenly called his tank (It’s not a tank, says Kemp, who compares the machine to a charming but deadly woodlouse that shoots cannon balls from all directions as it twists across the battlefield). Were one to follow his drawing, one would construct wheels that turn in opposite directions. Also, the nine men in the conical contraption turning the axles would have gone deaf from the cacophony, according to Kemp.

And Vitruvian Man, one of history’s most famous anatomical drawings, wisely rejiggered the square and circle in which the figure is circumscribed to avoid predecessors’ mistakes. But Leonardo’s solution was still unsound, including an improperly-joined leg and hip.

“There is actually a lot of contrivance going on,” Kemp says of this work. “It’s such great art. It’s so cogent that we don’t notice that it’s got all sorts of tricky things going on.”

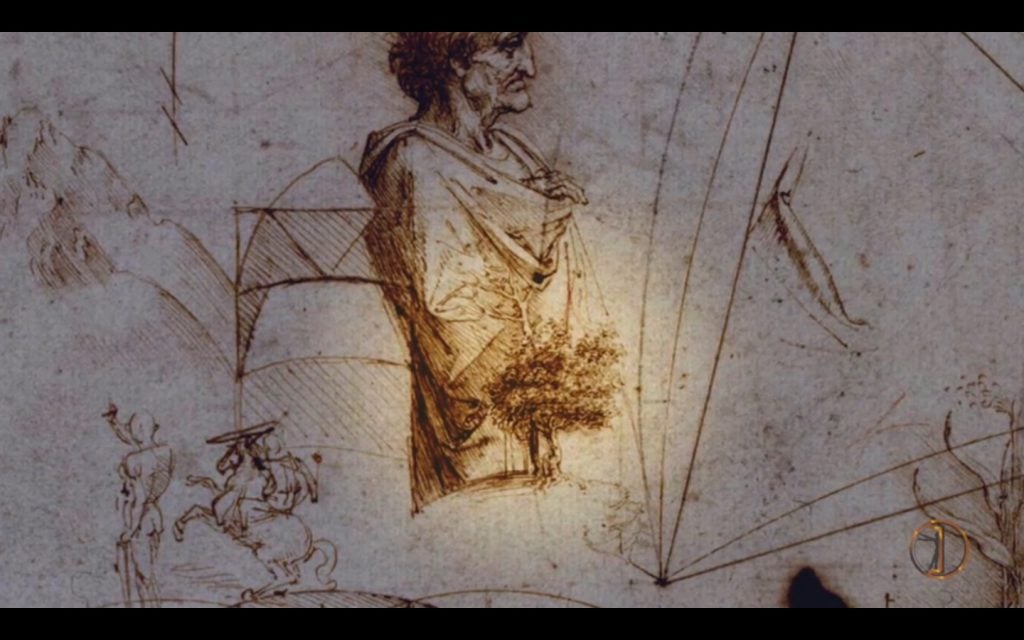

A still from Martin Kemp’s Da Vinci Masterclass.

Leonardo also failed to design a perpetual-motion machine (that would have been useful) and in squaring the circle—that is drawing a square with the exact same area as a corresponding circle. One night, Leonardo thought he solved it and recorded the time in the margin of a drawing. “Like so many ideas we have late in the evening, of course it didn’t work,” Kemp says.

Da Vinci didn’t record angsty memories, so we don’t know if he was discouraged when, for example, a giant crossbow wouldn’t fire as he calculated. “What we do have is a little recurrent refrain, which he writes down in various points, which is Di mi se mai fu fatta alcuna cosa—‘Tell me if anything were ever done,’” Kemp told Artnet News.

He embraced uncertainty

Leonardo strove to understand how the world worked, so he could harness nature for military and other engineering enterprises. But as an older man, he also embraced uncertainty, and what former U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld would call “unknown unknowns.”

“We don’t think about Leonardo being about uncertainty,” Kemp says in the course. But the young man who called himself “a disciple of experience,” and said “the eye is the chief sense,” grew into a mature artist, who saw sight as error-prone.

Leonardo liked that a red chalk drawing on red paper is “almost not seeable,” Kemp says in the course, and he understood increasingly that the eye is inadequate to understand bodily edges or theological truth.

Da Vinci blurred Christ’s features deliberately in Salvator Mundi to make the divine figure unseeable. “If you look in to see more clearly, you don’t get certainty. You get uncertainty,” Kemp says in the course. In Saint John the Baptist, the figure points heavenward—to the world outside what humans understand readily. “He’s losing faith in optics as carrying the whole truth,” Kemp says. “There is something beyond. Something mysterious. Something unknowable.”

Last Supper was the final painting Leonardo did in perspective, according to Kemp. “I think he’s lost faith in the geometry of optics.”

He followed ugly people around

Among the small notebooks Leonardo wore on his belt, he filled pages with what Kemp calls “pen men,” rapid sketches of people in motion. He also followed ugly people around and drew them—what Kemp calls “extreme physiognomonics.”

“He believes that the beautiful needed the grotesque,” Kemp told Artnet News. “It’s like light and shade. They belong together to define things.”

Da Vinci was interested in how the mind and soul were manifest in physical traits (concetto del anima), as in Last Supper, when Judas—knowing he would betray Christ—sits rigidly with his neck tendons standing out.

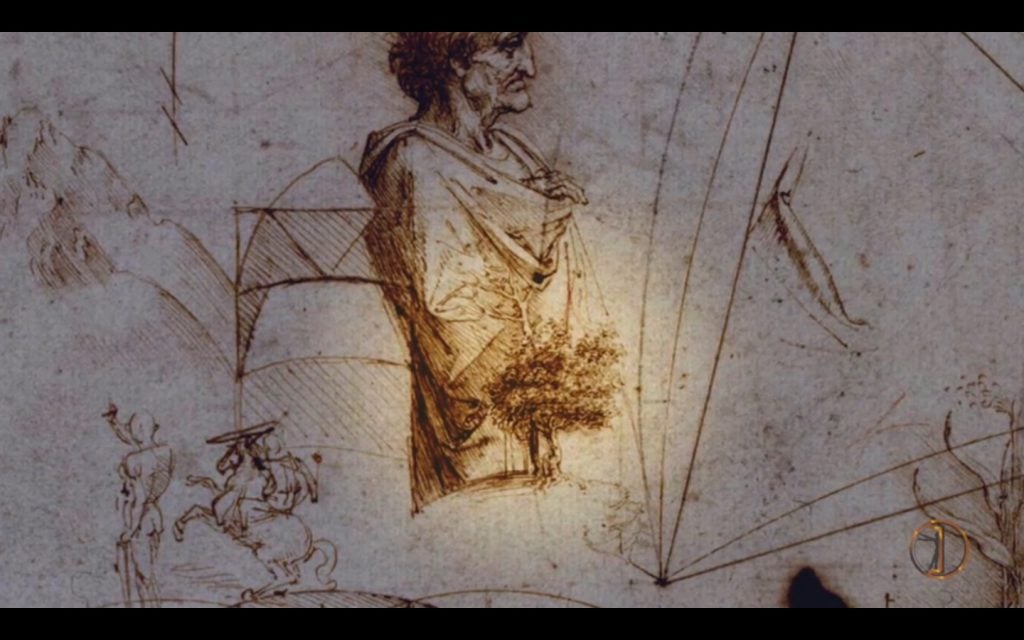

A drawing of Leonardo’s that its owner Giorgio Vasari called King of the Gypsies is pricked for transfer onto canvas, Kemp thinks. He figures it was intended for a painting of Christ carrying the cross, or of a flagellation of Christ. “It’s for a grotesque man, who is flagellating or abusing Christ in some kind of way,” Kemp says in the course. Of another work, which Kemp connects to the “marriage of fools” genre, he notes that Da Vinci had a sense of humor.

“He wrote jokes—and fairly obscene jokes which we don’t need in these circumstances. We always regard these great artists as rather po-faced, but he enjoyed a laugh,” Kemp says in the course. “In a way, these are risible characters literally to be laughed at, and he’s assuaging our fear of the grotesque.”

He had a natural inclination

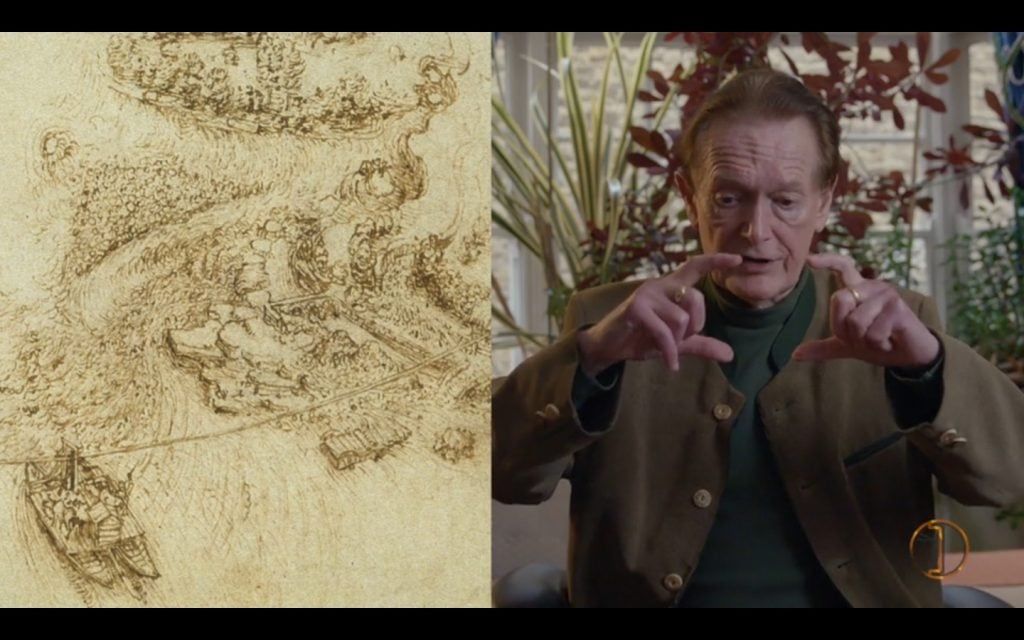

Many associate Leonardo with portraits and biblical scenes, but the artist who emerges from the masterclass is also obsessed with nature. At various points, he saw connections between human veins and river tributaries, internal organs and trees. Typical notebook pages are collages of different forms: clouds, people, horses, trees, geometric shapes, water, storms, and towers. “He didn’t see these things as separate,” Kemp says in the class. “They all flowed into each other.”

Leonardo believed understanding nature facilitated grasping human nature, and vice versa. “We are a little world,” Kemp says in the course. Da Vinci called rivers “veins” or “vessels” of water, and several drawings in the Codex Leicester, which Bill Gates owns, bear this out. One of Kemp’s favorite drawings by Da Vinci depicts an old man—whom he calls St. Joseph—looking to the right. On the opposite page, Leonardo drew water. He didn’t intend the figure to gaze at the water, “but that’s how it functions now,” Kemp says in the class.

Many have likely seen Mona Lisa without looking closely at the landscapes in the background. Kemp points out the high lake in the top right, which flows to the lower lake on the left. Beneath that, a dried river bed leads (behind the figure) to a bridge on the right over a river. Leonardo believed that Arno was two lakes, which connected over the centuries, so one can speculate that the dried river bed in the picture will flood, which will sweep away the bridge on the right.

“Something extraordinary is going to happen,” Kemp says in the course, noting corresponding rivulets in the hair and clothing. “There’s an enormous amount of what you might call geology and physics going on in this.”

He kept secrets

Da Vinci trained in the studio of sculptor Andrea del Verrocchio, a “jack-of-all-trades” who was also an engineer, according to Kemp. Notedly, Verrocchio figured out how to place the gold ball on the Florence Duomo dome—a project which brought Leonardo in contact with Brunelleschi’s dome as well as his machines. (For his “legendary machines,” Brunelleschi was called “the new Daedalus,” per Kemp.)

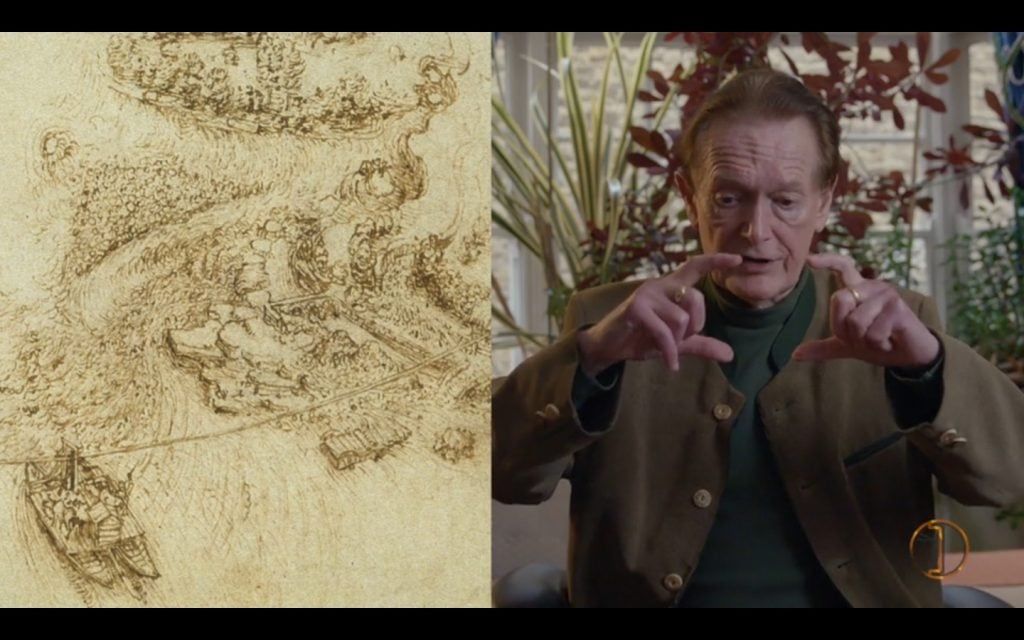

A still from Martin Kemp’s Da Vinci Masterclass.

Many of Leonardo’s designs were instruments of war and violence, but his interests lay in fight and flight—in this case a “man-powered bird.” One flying machine is mistaken for a helicopter. “Where on earth was a man or woman going to stand on that as it revolves?” Kemp asks in the class. Instead, a wound-up spring would release the “very ingenious” object into the air.

Realizing a bird’s wing resembles a human arm skeletally, Leonardo created test wings in secret while working in the Corte Vecchia in Milan, now part of the royal palace. In a note, he directed assistants to make the wings out of view of those working on the cathedral dome, “both probably because he didn’t want to be seen with something which was going to fail, but also, he didn’t want people laughing at him, deriding him, and stealing his secrets,” Kemp says in the course.

Leonardo never overcame the height-to-weight ratio, so his ornithopter came up short.

In the hills surrounding Florence, Leonardo sought not only to draw and understand how birds flew, but also to better grasp airflow. To him, air resembled waves moving on a beach.

“Leonardo didn’t achieve flight in his own lifetime, but he knew where the answers lay,” Kemp says in the course, noting a television program in which he was involved followed Leonardo’s designs and created a machine, which a person powers, that can fly. Leonardo’s act of human creativity, to Kemp, symbolizes the best of what humans can accomplish.