Art History

Agnes Martin Is the Quiet Star of the New York Sales. Here’s Why $18.7 Million Is Still a Bargain

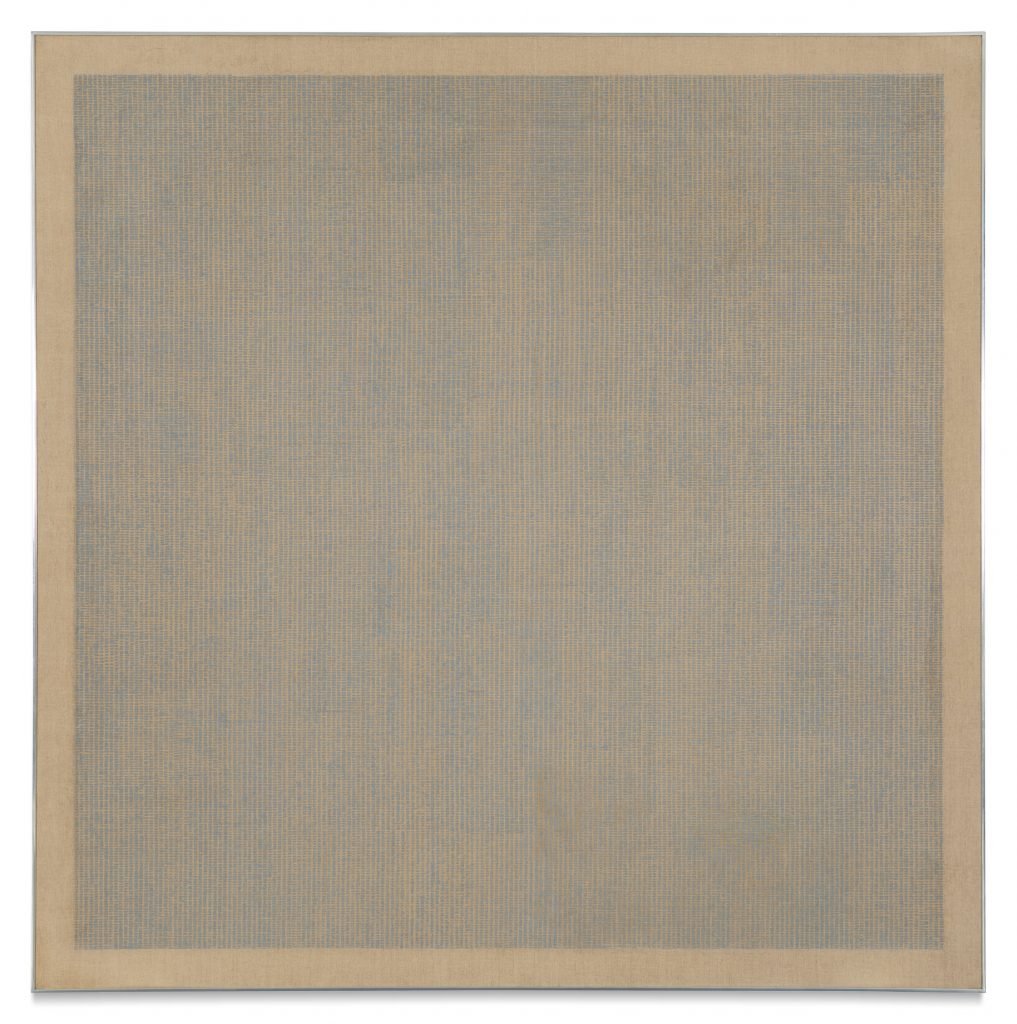

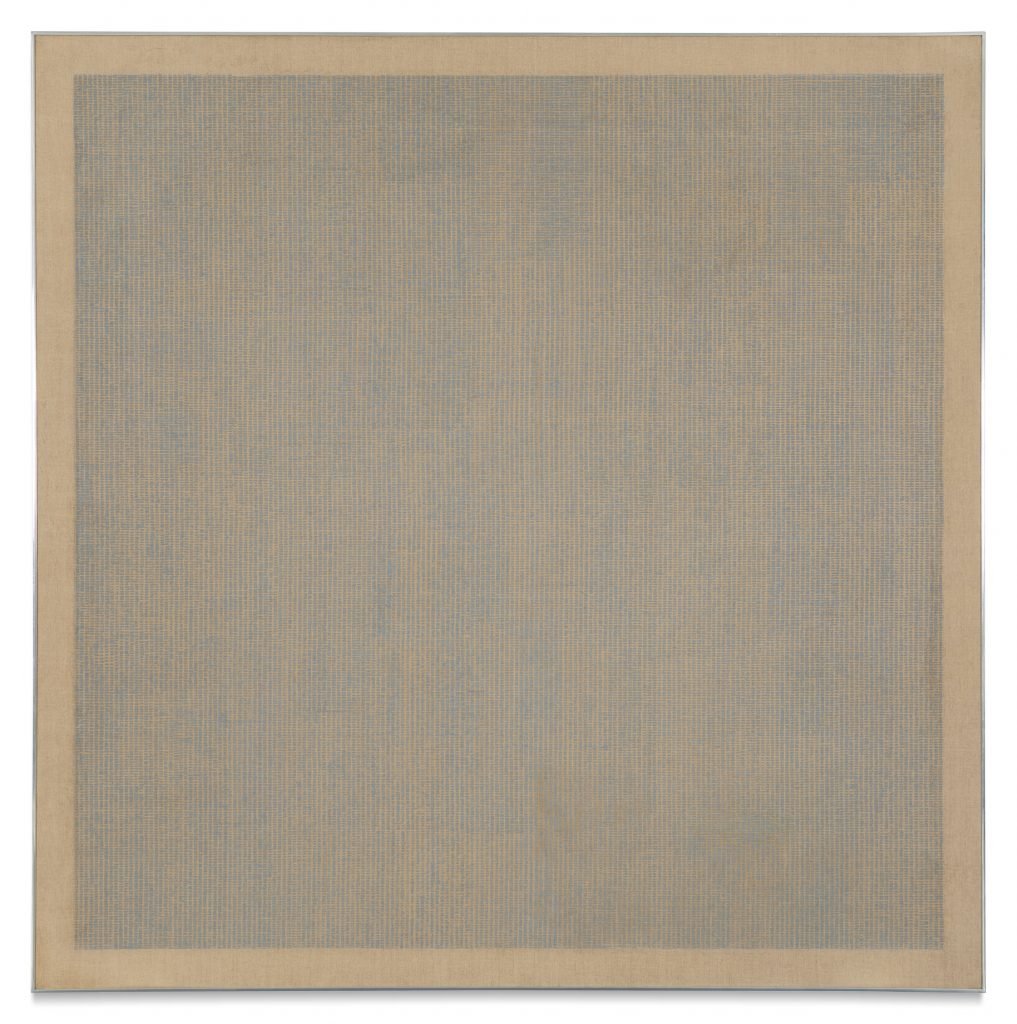

Her mammoth canvas 'Grey Stone II' exemplifies how Martin's methodical approach ushered in a new age of Minimalism.

Her mammoth canvas 'Grey Stone II' exemplifies how Martin's methodical approach ushered in a new age of Minimalism.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

In a moment of dramatic suspense, a slow but determined bidding war broke out over Agnes Martin’s Grey Stone II (1961) during the Emily Fisher Landau Collection sale at Sotheby’s New York on Wednesday evening. The painting was one of the sale’s standout lots, reflected in its hammer price of $16 million ($18.7 million with fees), which easily doubled the cautious presale estimate of $6 million–$8 million backed by a guarantee, and set a new record for the artist.

Martin is best known for her subtle grid paintings, of which Grey Stone II is a rare early example. These works aren’t attention-grabbers like some of the more explosive works of the 1960s and 1950s by artists like Pollock or Warhol. Rather, their small-scale repetitions pull the viewer into a state of sustained contemplation.

Without ever having to make a splash, Martin’s quietly powerful compositions have made her one of the defining foremothers of Minimalism and, by extension, a key player in the artistic reset that would usher in a new age of Postmodernism. These experimental, wholly original works led the charge as the artists of 1960s New York radically deconstructed, reduced, and investigated form.

Greystone II is a prototypical example of Martin’s pioneering work. Here are three facts that explain why collectors sought it out so passionately.

Sotheby’s auctioneer Oliver Barker takes bids for Agnes Martin’s painting Grey Stone II during Sotheby’s auction of the Emily Fisher Landau collection in New York City on November 8, 2023. Photo: Angela Weiss/AFP via Getty Images.

Martin began making the grids that would become her signature in the late 1950s. Despite first appearances, these spare geometric forms are filled with unpredictable rhythms. Within an underlying system of rules, our attention is drawn to deviation rather than conformity. Where we might expect a perfectly straight line, we instead notice the minute slant or waver that make each and every one of Martin’s handmade markings unique.

In the endlessly repeated movements that make up Grey Stone II, every tiny stroke of the pencil or brush of blue-grey pigment was inevitably applied with more or less pressure or at a slightly different angle. This element of chance chimes with the grid’s roots, which is based not in mathematics but in nature. “When I first made a grid I happened to be thinking of the innocence of trees and then this grid came into my mind and I thought it represented innocence, and I still do,” Martin recalled in 1989. “I painted it and then I was satisfied. I thought, this is my vision.”

By stripping back the detail, Martin was able to reduce her compositions down to the core underlying patterns that make up our world. The resulting forms are both painstakingly specific, lasting records of a series of intimate acts between artist and artwork, and yet unquestionably universal.

Much like the cells that accumulate to create life, each of Martin’s modest marks elide to make a grander scheme that stands out for its soft serenity. “This work is a form of meditation,” said Sotheby’s specialist Courtney Kremers in a promotional video. “An object that represents time and process. All of those things combined are a reflection, quite simply, of life.”

Giotto di Bondone, Saint Francis of Assisi (San Francesco) preaching to the birds, detail of the predella of St Francis of Assisi receiving the Stigmata. Photo by Leemage/Corbis via Getty Images.

As well as pencil and oil paint, Martin used gold leaf applied with gesso to make Grey Stone II. On just a handful of occasions before 1964, she opted to use this opulent material to elevate her typically humble materials and methods. The painting is exceptionally rare because Martin applied gold to a large scale canvas like Grey Stone II, which measures 72 inches by 72 inches, only three times. The other two notable examples are Friendship (1963) in the permanent collection at MoMA and Night Sea (1963) at SFMoMA.

Inevitably, the material recalls the decorative and rarified use of gold-grounds in medieval religious art, including in the works of early Italian Old Masters like Cimabue, Giotto, Duccio, and Fra Angelico, whose innovations paved the way for the Renaissance. Many centuries ago, art was illuminated by the meticulous application of gold, one leaf at a time. This association foregrounds how Martin’s own radically methodical approach is just part of the process of creating a masterpiece.

“Gold leaf is a material that in Martin’s hand becomes something wholly different,” noted Kremers of the artist’s inventive modern-day revival of the medium. “It’s a material that I think she chose because it really communicates joy, but there is a boldness to gold as a material. It’s the material of icons.”

Coenties Slip in the downtown financial district of New York City during the 1930s. Photo by Charles Phelps Cushing/ClassicStock/Getty Images.

“When you think of 1961 as a year, it was a loud, bold moment in the art world,” commented Kremers, referencing Andy Warhol’s Superman, Roy Litchenstein’s Look Mickey and Lucio Fontana’s slashed canvases. “In the face of all this really loud, bold art, Agnes Martin creates something that is defiantly quiet, defiantly calm in a sense.”