Politics

‘Hamilton’ Popularized the Legacy of Revolutionary War General Philip Schuyler. It Also Helped Get His Statue Booted From Albany

The statue had stood for nearly 100 years.

The statue had stood for nearly 100 years.

Sarah Cascone

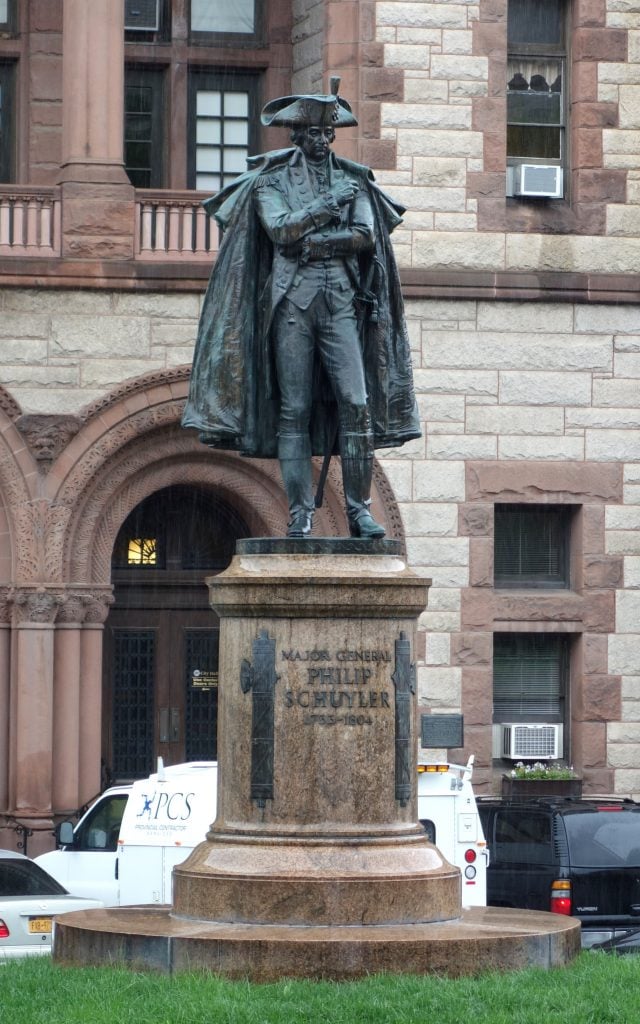

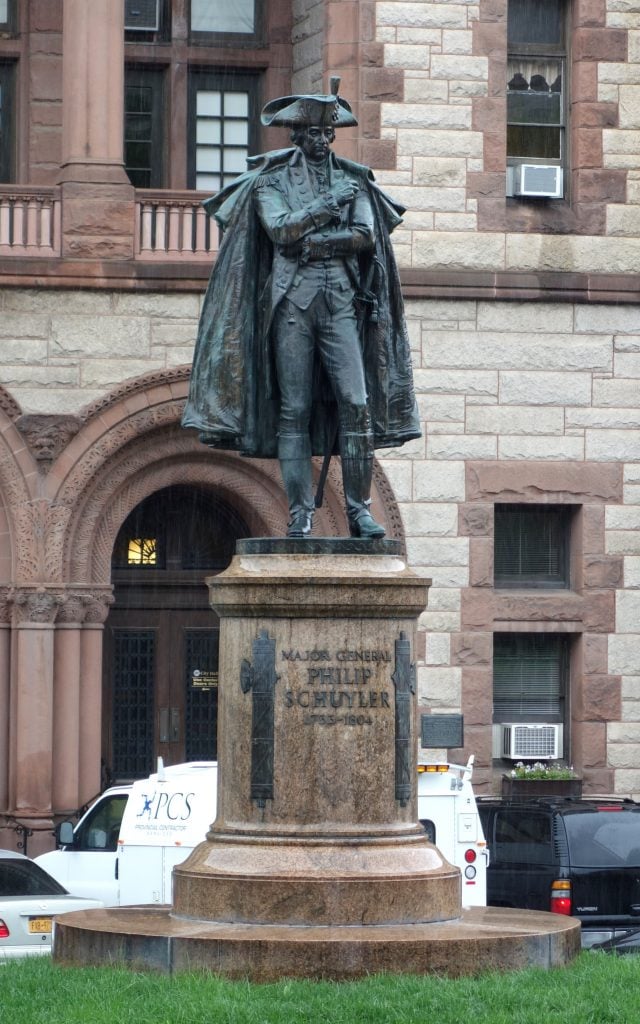

For nearly 100 years, a seven-foot-tall bronze statue of Philip Schuyler, a prominent figure in early America who is best known today as Alexander Hamilton’s father-in-law, has stood outside Albany’s City Hall—until now.

This month, the monument was removed and put into storage because Schuyler—in addition to serving as a U.S. senator and Revolutionary War general—owned enslaved people.

Created by Scottish-born sculptor John Massey Rhind, the statue was originally a gift from a local brewer named George Hawley back in 1925.

But in the 21st-century United States, Schuyler had become quite an obscure figure—until the 2015 release of Lin Manuel Miranda’s blockbuster musical Hamilton featured him as a prominent, if off-stage character: The wealthy and powerful father of the title character’s wife, Eliza Schuyler, and her sisters Angelica and Peggy.

Breaking – statue of Gen Philip Schuyler removed from outside Albany City Hall and driven away to be put into storage @WNYT pic.twitter.com/AXqZBYcpCY

— Subrina Dhammi (@SubrinaDhammi) June 10, 2023

The play drew attention to the statue, attracting fans posing for selfies—but it also opened Schuyler up to closer scrutiny, helping publicize his documented ties to slavery.

The family’s slaveholding dates back to Schuyler’s great-grandfather Philip Pieterse Schuyler, who had immigrated to Albany from the Netherlands around 1650. Construction workers had discovered an unmarked cemetery with the remains of enslaved people, now known as the Schuyler Flatts Burial Ground, on the former Schuyler property in 2005.

The Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site includes exhibitions about some of the enslaved members of the household, including Schuyler’s butler and a woman who fled the property in search of freedom. The museum estimates that Schuyler enslaved about 40 people.

The Schuyler Mansion in Albany, New York (2011). Photo by Matt H. Wade, @thatmattwade (portfolio), Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

In June 2020, Albany Mayor Kathy Sheehan issued an executive order to remove the Schuyler statue, stating that “the city of Albany is long overdue in confronting its history of racism and inequality, the origins of which may be traced back to slaveholders in the colonial era such as Philip Schuyler.”

At the time, the murder of George Floyd had sparked nationwide protests against police brutality and racism. The Black Lives Matter movement also birthed a widespread reckoning surrounding the problematic legacies of historical figures honored in public places, particularly of Confederate leaders. Since 2020, prominent Robert E. Lee statues have been removed from the streets of numerous cities, including Charlottesville, Roanoke, and Richmond, Virginia.

Such initiatives have proved controversial, sometimes prompting extended legal challenges. Florida enacted a law that made defacing or damaging Confederate monuments a felony in 2021. Likewise, Schuyler’s ouster was not without its critics, due to his importance in Albany history.

“Can you imagine Boston turning its back on Sam Adams or Virginia denying Thomas Jefferson?” Jeff Perlee, a Republican in the Albany County Legislature, told the New York Times. “The leaders in those places, I think, are sophisticated enough to understand the historical context and the whole measure of attributes and negative features of historical figures. And unfortunately, the leaders in Albany don’t.”

Taking down the statue, which cost $40,000, according to the Times Union, was “attempting to erase history,” Representative Elise Stefanik, chair of the House Republican Conference, wrote on Twitter.

“I understand people’s strong feelings about this and these decisions are never easy,” Sheehan told the Times Union. “While this is a person who did great things in history, and is rightly remembered for all of his amazing accomplishments, he is also a man who enslaved dozens of African Americans. We have to figure out how we contextualize that and tell the whole story.”

The city plans to find a new place to display the statue at a museum or institution, where it can be presented in the context both of Schuyler’s accomplishments and also his role in slavery.

Sheehan has proposed creating an Albany Monument Commission to determine the work’s new home, which could be the city’s Academy Park.

Workers discovered a time capsule inside its base while deinstalling the piece, the contents of which are now being studied at the Albany Institute of History and Art.