Opinion

Christmas in May with Andy Warhol

THE DAILY PIC: On auction at Artnet, Warhol's last cards evoke holidays past.

THE DAILY PIC: On auction at Artnet, Warhol's last cards evoke holidays past.

Blake Gopnik

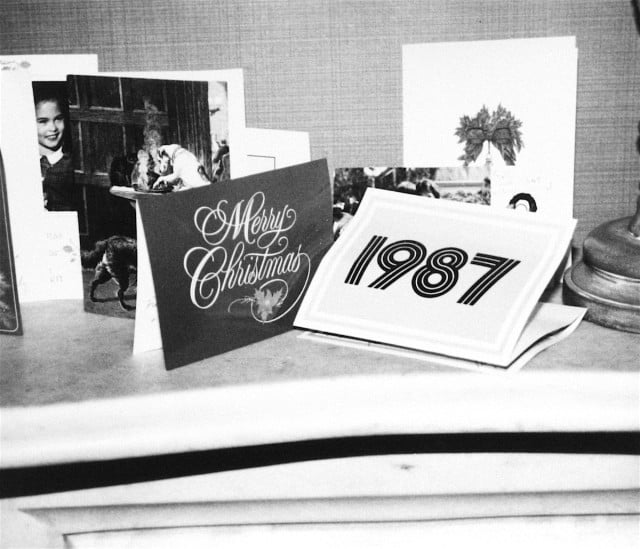

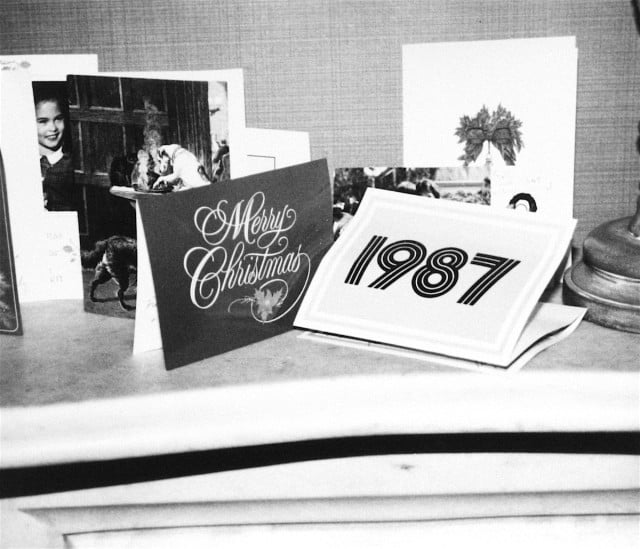

THE DAILY PIC (#1540): This cheerful little image of Christmas cards, shot by Andy Warhol or a close associate around December of 1986, has a sad underpinning: It pictures the last batch of holiday cards that Warhol would receive, because he died almost exactly two months later. The print is in an exhibition of Warholian photos now on view at the Artnet headquarters in New York, to go with the online auction of those photos that ends on May 4. (All photos that come out of the Warhol studio count as being by him, even when we can’t tell who snapped the shutter, in just the way that all of a great architect’s projects will bear his or her name, even though they may have been executed or even designed by employees in the firm.)

Looking at that record of Warhol’s last Christmas on earth reminded me of the place Christmas had had in his life and career. His archive at the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh is overflowing with the hundreds of Christmas cards that were sent to him and his mother Julia during the two decades she lived with him, and then to him and his boyfriends in his final 15 years. And those are just the cards he chose not to throw out. (Unless he kept every last one he was sent – not impossible with a junk-keeper like him.)

Warhol was also an eager sender of Christmas cards, especially in his early years: One of his first serious attempts at modern art is a 1947 photogram that he sent with holiday greetings to his college friend George Klauber, whom he later billed as his first mentor in gay life. Another card, sent to Klauber at Christmas the following year, is one of the earliest expressions of the fey sensibility that Warhol went on to cultivate: It shows five male ballet dancers, in red shorty-shorts and mauve shirts, prancing merrily about on point. (Another version includes fluttering butterflies.)

In the 1950s, the equally fey artist’s books Warhol turned out, and the exhibitions that went with them, were almost always targeted at a holiday audience, and especially at his clients who warranted Christmas gifts. Warhol was seen as such a natural cheer-giver that he was commissioned to illustrate commercial Christmas cards as well as a host of seasonal features in magazines. He was also asked to design actual Christmas trees and holiday displays, which must have reminded him of the time he spent as a teenager working with the window decorators at Horne’s department store in Pittsburgh, whose famous Christmas windows drew oglers from miles around. Those decorators were very likely the first flamboyant gays he’d ever come across, and must have given him hope for his own future place in the world.

In the 1950s, Warhol’s business as an illustrator made him part of a retail ecosystem that, then as now, depended on Christmas sales. But his ties to the holiday may have been more complex than for some other Christian Americans. Although he’s often described as simply a “Catholic” – or sometimes even as a “Roman Catholic” – that gets his religion quite wrong. He was raised as what was then called a Greek Catholic, which means that his family and their fellow parishioners mostly adhered to the rituals and ideas of the Eastern Orthodox church, even though their administrative fealty was to the Pope in Rome. In the 1930s in Pittsburgh, little Andy Warhola would have celebrated Christmas on a different date, and in quite a different way, from most of the other Christian kids on his street. (The neighbors also included a number of Jews, some of whom Warhol was close to.) “We were a bit ashamed,” said his eldest brother Paul. “Everyone celebrated Christmas on December 25, and we didn’t until two weeks later. At school we had to make up all kinds of excuses to get us out of attending on that day. Once in the thirties, when Dad didn’t have any work, we didn’t get any gifts for Christmas. We all cried.”

So Christmas, for Warhol, may not have engendered quite the feelings of belonging that it does for many American Christians, and even for many non-believing Americans. It may have reinforced the outsider status that was central to Warhol’s entire being, and that helped power his art.

Christmas may have impinged on Warhol, even more than on the rest of us, as a festival of consumer culture. And that was something he could work with. (©The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc./Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York)

For a full survey of past Daily Pics visit blakegopnik.com/archive.