Last month, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit declared that a notable group of Andy Warhol paintings—his famed “Prince Series”—infringed the copyright of the photographer whose image served as the basis for the body of work.

The court’s controversial decision, grounded in a narrow understanding of copyright law’s “fair use” provision, may have granted judges more power in evaluating artistic expression than some might like. But less than two weeks later, the Supreme Court provided a more expansive understanding of fair use, this time in Google v. Oracle, a case involving the copying of computer software code.

Technology and art are very different. Yet the Supreme Court’s recent decision suggests that the Second Circuit, which sits one rung down on the ladder of federal judicial authority, may have some further thinking to do about how copyright’s fair use doctrine applies when artists copy or reference existing images.

The Lawsuit

In 1984, Vanity Fair paid Lynn Goldsmith $400 to license the photograph she had taken of Prince three years prior in order to use it as an “artist reference” for an illustration in the magazine. The artist Vanity Fair had hired, unbeknownst to Goldsmith, was Andy Warhol.

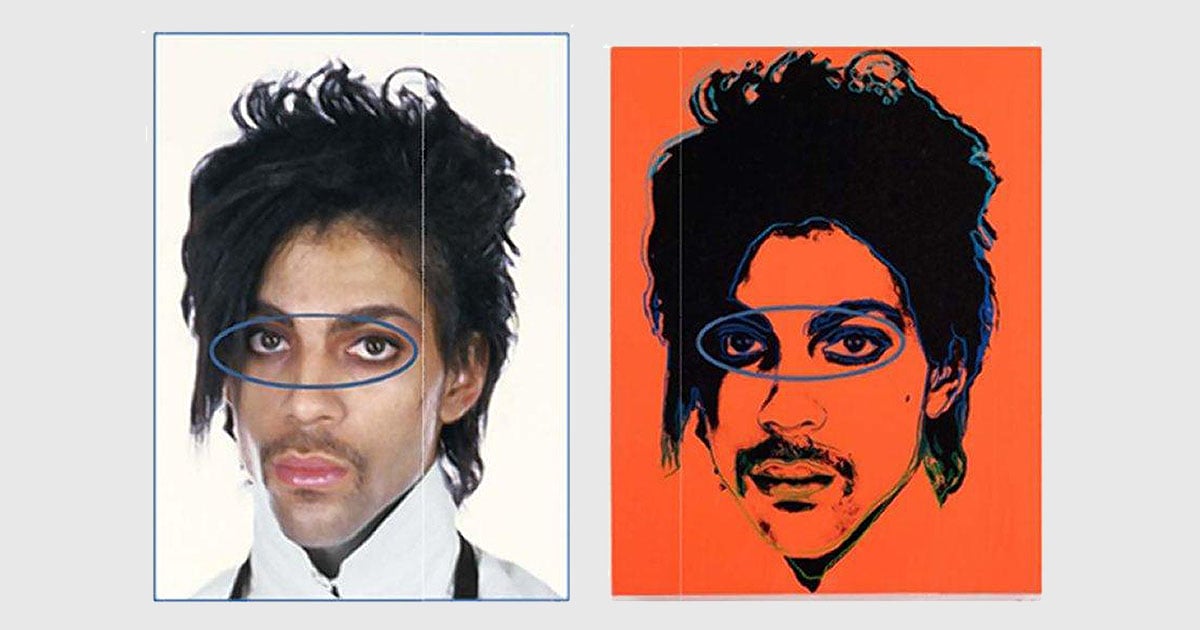

Warhol cropped the photograph down to Prince’s face and used it as the raw material for 16 works, one of which, pictured below at right, ran alongside an article on the musician.

Right: Lynn Goldsmith’s original photograph of Prince; left: Andy Warhol’s Orange Prince.

In 2016, Vanity Fair reprinted the same Warhol work as the cover for a special issue commemorating Prince’s death. This use was not covered by the original license, and Goldsmith made her displeasure known. The Andy Warhol Foundation responded by going on the offensive, seeking a declaratory judgment that the “Prince Series” did not infringe the Goldsmith photograph.

The foundation argued that Warhol’s use of the Goldsmith photo was fair use. (It has restated that view in an en banc petition filed last week asking the court to reconsider.) Viewed broadly, fair use is an exception to the usual copyright rules aimed at furthering the larger aim of copyright: to promote creativity in the arts. As the Supreme Court has explained, fair use permits one creator to use the work of another when forbidding that use “would stifle the very creativity which that law is designed to foster.”

(A canonical example of a fair use would be a parodic song which copies the melody of a famous song —such as 2Live Crew’s version of Roy Orbison’s “Pretty Woman,” upheld as fair use by the Supreme Court in 1994.)

In the Warhol case, the trial court judge agreed with the Warhol Foundation, holding that the Prince series was fair use, in large part because it transformed the original Goldsmith work to give it a new meaning. While the Goldsmith photograph portrays Prince, in the court’s words, as “not a comfortable person” and a “vulnerable human being,” the Prince Series portrays Prince as an “iconic, larger-than-life figure.” Such “transformative” use, in the district court’s view, creates something new, and is therefore the kind of use that is more likely to be fair use.

On appeal, the Second Circuit disagreed. That court found that Warhol’s use of the Goldsmith photograph was not “transformative” and, based in large part on that conclusion, went on to hold that Warhol’s Prince portrait did not qualify as fair.

A Question of Transformation

So what does this notion of “transformativeness” in copyright law actually mean? The core idea is that if a second work sufficiently changes the first, it becomes a new work worthy of protection. Though it is not the only element in evaluating fair use, the transformativeness concept has come to occupy a central place in legal analysis.

In fact, shortly after the Second Circuit’s decision in the Warhol case, the Supreme Court reaffirmed the importance of transformativeness when it held that Google’s unauthorized use in its Android operating system of 11,500 lines of code from Oracle’s Java SE program was transformative enough to qualify as fair use.

Such use, the Supreme Court stated in Google v. Oracle, “adds something new and important,” typically by shifting the original work’s purpose, meaning, or message—and, as a consequence, stimulates creativity. Google had done just that, the court held, when it used code from Oracle’s Java (a programming language that had previously been used mostly to build desktop applications) to build a new operating system for mobile phones—something Oracle had tried to do, but with little success.

If Google’s use was transformative, why wasn’t Warhol’s? Was it fair to say that Google’s use of 11,500 lines of code to make a new operating system was transformative but Andy Warhol’s use of Goldsmith’s photo to make Orange Prince was not?

Andy Warhol’s Prince illustration based on the Lynn Goldsmith photograph as it appeared in Vanity Fair, here reproduced in court documents.

In a sense, the Supreme Court in Google v. Oracle had an easier job than the Second Circuit did in Goldsmith v. Warhol. Whether Google had used Oracle’s code to create something new was a question the Supreme Court could answer simply by comparing Google’s software’s functionality with that of Oracle’s: Android provides a new functionality (that is, it works well on a mobile phone), meaning Google put elements of Oracle’s code to a new purpose.

By contrast, the appeals court in the Warhol case was facing questions not of functionality, but aesthetics. How is a court to determine whether Warhol’s use of the photograph changed its purpose, meaning, or message?

The Second Circuit argued that while it may have been Goldsmith’s intent to portray Prince as a vulnerable young artist, and Warhol’s “to strip Prince of that humanity and instead display him as a popular icon,” whether a work is transformative cannot depend merely on the artist’s intent.

Rather, for Warhol’s work to be transformative, “it must reasonably be perceived as embodying an entirely distinct artistic purpose, one that conveys ‘new meaning or message’ entirely separate from its source material.” In other words, the new meaning must not be linked to the source material itself but rather to something else the appropriating artist did with the work. It must flow from a new artistic vision—or so it must seem to the eye of a federal judge.

As an example of work that meets that standard, the Second Circuit pointed to two previous art cases. The first involved Jeff Koons’s painting Niagara (below right), which incorporated a photograph from a fashion magazine (below left). In that case, the court believed that Koons’s work gave a new meaning to the underlying photograph.

Left, a magazine advertisement used in Jeff Koons’s Niagra (2000). Courtesy of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

That same court, in a subsequent case involving the “Canal Zone” series by Richard Prince (example below right), which incorporated photographs of Rastafarians by Patrick Cariou (below left), held that most of the Prince works transformed the message of the Cariou works, turning Cariou’s classical portraits into something disjointed and frenetic.

Left, a Rastafarian by Patrick Cariou and right, an image from the “Canal Zone” series by Richard Prince.

What do the Koons and Prince works have in common? They’re both collages. They take bits and pieces from various works and arrange them into something new. Like Google’s use of some of the Oracle code, the underlying work becomes a building block in a larger creative edifice.

On the other hand, Warhol’s Prince work is based on a single source photo. The Warhol court thought that this difference mattered, noting that artworks previously deemed transformative “draw from numerous sources, rather than works that simply alter or recast a single work with a new aesthetic.” By contrast, the court held, Warhol’s Prince works “retain… the essential elements of the Goldsmith Photograph without significantly adding to or altering those elements.”

Was It Wrong?

The Supreme Court’s decision in the Google case casts some doubt on the lower court’s conclusion. Viewed abstractly, what Warhol has done with Goldsmith’s photo isn’t too different from what Google did with Oracle’s 11,500 lines of code. The code that Google took sits in Android, unchanged, just as the Goldsmith photo recognizably appears in Warhol’s Prince works. Google built a program around Oracle’s code that provides new functionality. Warhol also built a work around Goldsmith’s photo that provides something new. And under the Google decision, adding something “new and different” is sufficient to render the second work transformative of the first.

The real challenge in the Warhol case is articulating exactly what the “new and different” elements are. And this illustrates an age-old problem in copyright law that has never been solved, and that makes copyright risky for artists who, like Warhol, work through appropriation.

In Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Co., a classic copyright case from 1903, the Supreme Court considered whether circus posters, like the one shown below, were copyrightable.

An image from the Bleistein v. Donaldson Lithographing Co. case in 1903.

The defendant contended that copyright should not protect mere advertisements. But the famed Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes disagreed:

It would be a dangerous undertaking for persons trained only to the law to constitute themselves final judges of the worth of pictorial illustrations, outside of the narrowest and most obvious limits. At the one extreme, some works of genius would be sure to miss appreciation. Their very novelty would make them repulsive until the public had learned the new language in which their author spoke. It may be more than doubted, for instance, whether the etchings of Goya or the paintings of Manet would have been sure of protection when seen for the first time. At the other end, copyright would be denied to pictures which appealed to a public less educated than the judge. Yet if they command the interest of any public, they have a commercial value—it would be bold to say that they have not an aesthetic and educational value—and the taste of any public is not to be treated with contempt.

Holmes’ argument is that copyright law should not engage in aesthetic discrimination. But isn’t that precisely what’s going on in the Warhol case? The court sees the Prince and Koons collages as transformative because they have the quality of cut-and-paste that makes the artist’s contribution hard to miss, even if the particular message that the appropriating artist is sending is difficult to distill.

Koons helped his case by testifying to his intent to “comment on the ways in which some of our most basic appetites—for food, play, and sex—are mediated by popular images.” Richard Prince claimed that he “[doesn’t] have any interest in what [another artist’s] original intent is because … what I do is completely try to change it into something that’s completely different.”

Unlike Koons or Prince, Andy Warhol isn’t able to speak for himself. (Though given Warhol’s famously cryptic utterances, it is anyone’s guess if it would have helped.) And the power of Warhol’s transformative work in his “Prince Series” may be more difficult for judges to apprehend.

On a technical level, the changes may seem modest: Warhol cropped Goldsmith’s photograph and removed some of the humanizing details. He then boldly outlined Prince’s face against various brightly colored backgrounds. But to our eyes, the Warhol work just communicates an entirely different feeling than the Goldsmith photograph. The Goldsmith photo is a portrait. The Warhol works are a sort of religious iconography: They place Prince in the American pantheon.

It is unclear precisely how Warhol achieves this transformation; Warhol’s ineffability is entwined with his greatness. But it is clear—at least to us—that Warhol does in fact produce work that is both recognizably based on the Goldsmith photo and yet indisputably new.

The question is what courts can see in an artwork, and what they cannot. It’s easy for courts to see Google’s transformative work—it’s visible in the literally millions of lines of new code that Google wrote to create Android. It’s much more difficult to see, or to explain, exactly what Warhol’s transformative contribution was.

In the end, the Second Circuit’s ruling may be less about Warhol and more about, as Justice Holmes warned, that judges have not yet learned the language that artists like Warhol are speaking. As the Google decision suggested, grafting new materials onto existing material seems inherently transformative. But it is really more additive. Truly transforming an existing work, as Warhol did, is more alchemical, more mysterious, and more likely to be ignored—or even, as in this case, condemned.

Christopher Sprigman is the Murray and Kathleen Bring Professor of Law at New York University. Kal Raustiala is the Promise Institute Chair in Comparative and International Law at UCLA School of Law.