The U.S. Supreme Court has agreed to hear an unusual case involving copyright issues, a commissioned portrait of the late rock star Prince, and Pop art icon Andy Warhol. The decision may have big implications for artists who appropriate or remix existing images, an area of law that has long remained murky.

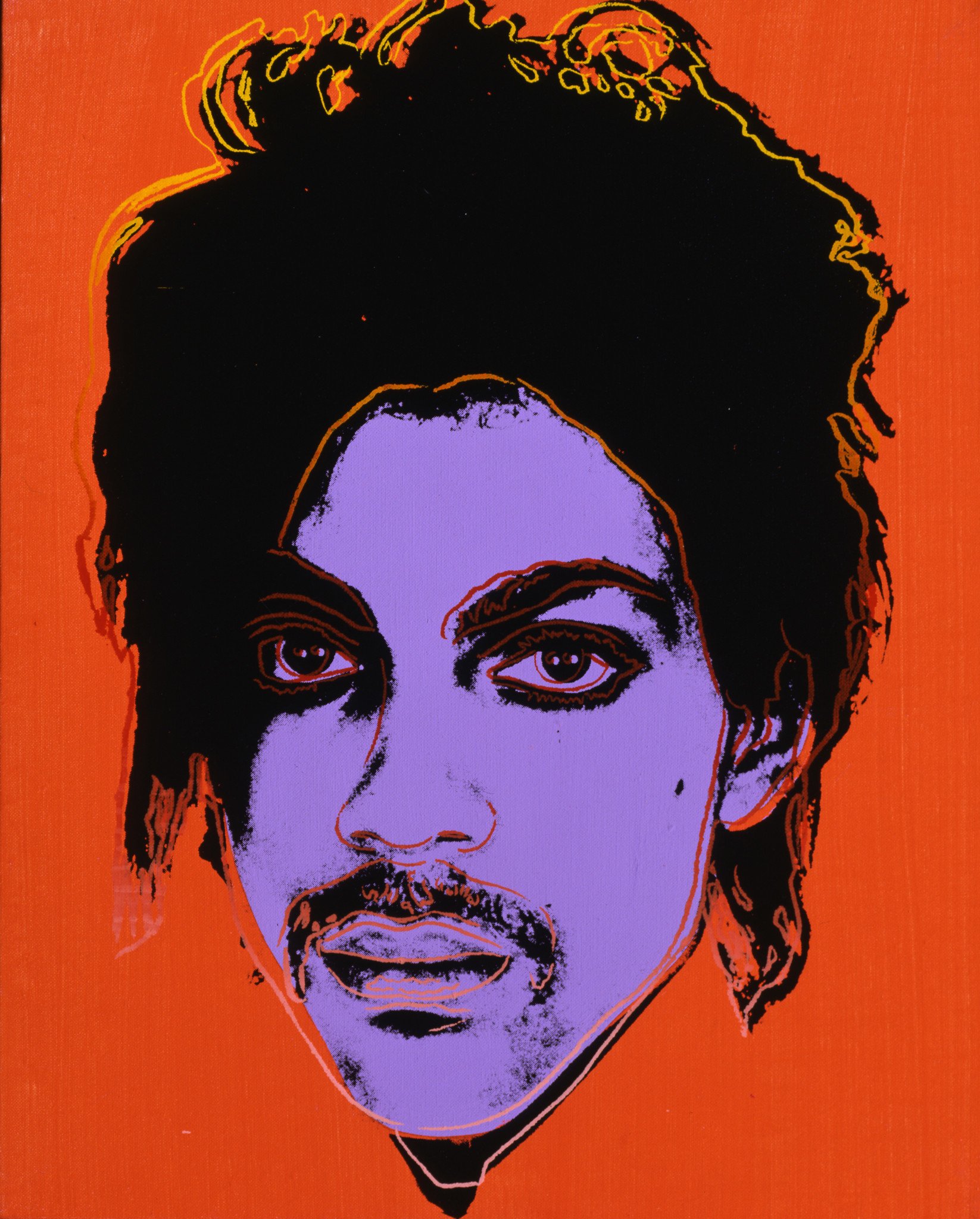

The court will rule on whether Andy Warhol sufficiently “transformed” an image of musician Prince taken by photographer Lynn Goldsmith when he used it to create his colorful “Prince Series.”

The dispute, which first came to light in 2017, has already taken enough twists and turns to give a fan or legal observer whiplash.

Goldsmith initially shot the image of Prince while on assignment for Newsweek in 1981, but it was never published. In 1984, Vanity Fair licensed one of her portraits of the singer for an illustration by Warhol. The artist ultimately made an entire series based on the photo (which he did not license himself). Goldsmith only learned about the works in 2016, when Vanity Fair republished them after Prince’s death without crediting her.

The Andy Warhol Foundation filed a pre-emptive lawsuit in April 2017 asking the court for a declaratory judgment stating that the “Prince Series” did not violate Goldsmith’s copyright. (A countersuit from the photographer soon followed.) In 2019, a New York federal court concluded that Warhol’s use was indeed kosher. But in March 2021, an appeals court reversed the ruling, siding with Goldsmith and describing the two artists’ works as “substantially similar… as a matter of law.”

The Warhol Foundation immediately voiced its intent to appeal—and now, it will get the chance to make its case in the highest court in the country. The foundation said the appeals court ruling “casts a cloud of legal uncertainty over an entire genre of visual art” and would threaten “a sea-change in the law of copyright.”

“The ‘fair use’ doctrine has for centuries been a cornerstone of creativity in our culture,” said Andy Gass, a partner in the copyright practice of Latham & Watkins, which is representing the Warhol Foundation. “Our goal in this case is to preserve the breadth of protection it affords for all—from the Andy Warhols of the world, to those just embarking on their own process of exploration and innovation.”

Goldsmith’s attorney did not immediately respond to Artnet News’s request for comment.

Dean Nicyper, a partner at Withers who is not involved in the case, said the Supreme Court’s approach is difficult to predict. Questions around fair use have swirled since the 2013 ruling in Cariou v. Prince, which controversially found that appropriation artist Richard Prince had not violated Patrick Cariou’s copyright by altering a number of photos from Cariou’s 2000 book, Yes, Rasta, for the 2008 series “Canal Zone.” (Cariou appealed the verdict, and the two artists eventually settled out of court.)

“Sometimes the Supreme Court will take a decision to clarify law in different areas,” Nicyper told Artnet News. “There are many different aspects of this case, aside from just clarifying the fair use factors and whether they want to address the extent of transformative use.”