Art History

Art Bites: Could Monet See Into the Ultraviolet Spectrum?

At the twilight of his career, Monet was going blind. Surgery restored his eyesight. But did it give him the uncanny vision of an insect?

“Monet is only an eye, but by God what an eye!” exclaimed Paul Cézanne in double-edged praise of his painting peer, the revered Impressionist master Claude Monet. It is unknown if Cézanne was aware that Monet did in fact possess superhuman vision.

In 1912, Monet’s exalted eyes came under threat when he began developing cataracts; a medical consultation found that the lenses of his eyes were clouding, blocking the light as it passed through. He was facing an artist’s worst nightmare: he was going blind. The cataracts may have just been a side effect of age—Monet was in his 70s, after all—but there is also speculation that lead-based paint was the culprit behind his retinal deterioration.

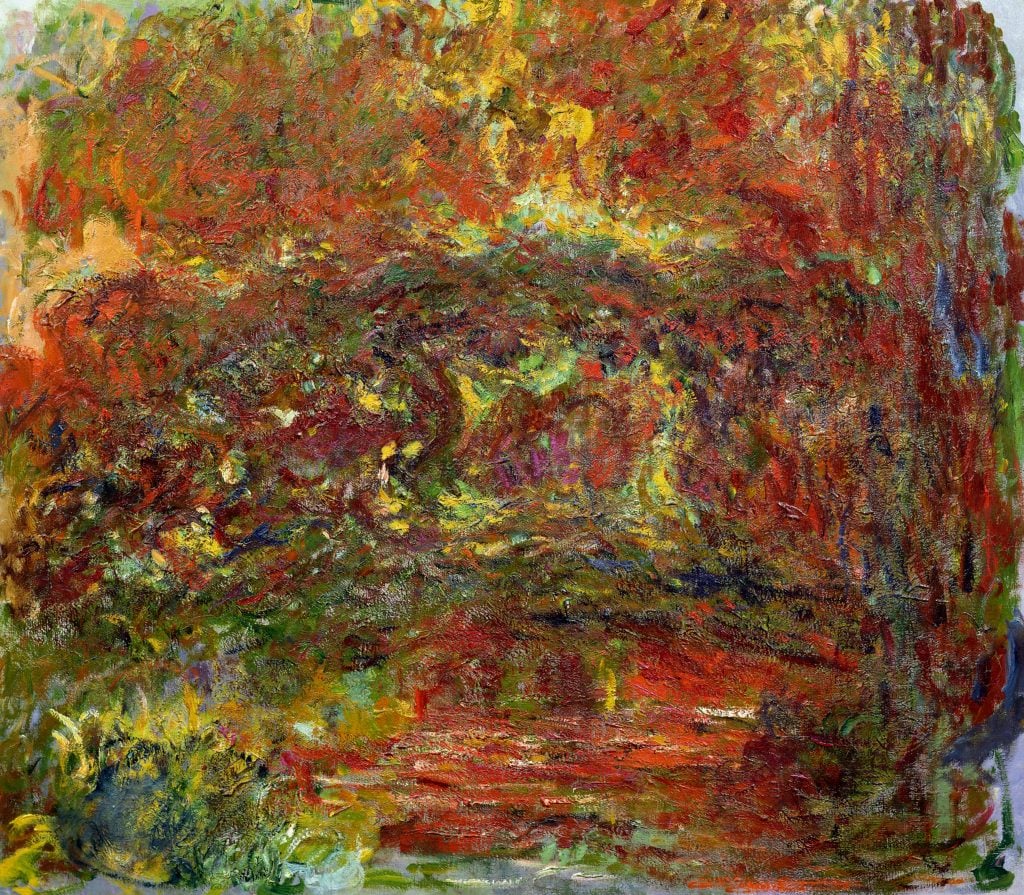

Claude Monet, The Japanese bridge (Le Pont Japonais) (1918–24). This is the very same bridge Monet has painted numerous times, except this one was made while he suffered from cataracts. As such, the a distinctive figure of the bridge is barely visible. Photo: Fine Art Images/Heritage Images via Getty Images.

Monet’s vision loss translated into his work. No longer able to distinguish between hues and tones, he resorted to painting by developing habits, like placing the same color on the exact same spot on his palette, and labeling his paint tubes with huge block print. He reportedly destroyed several canvases in fits of frustration.

The palettes in his paintings dampened from iridescent pastels to muddied monochromes, thick with heavy dabs of crimson and chartreuse. His coarse brushstrokes belied the appearance of distinctive figures, veering his work into the realm of abstraction.

Claude Monet and company at the water lily pond in Giverny, 1900. Photo: Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images.

A decade of cataract progression later, Monet had just agreed to paint a series of water lily paintings for the French government when a doctor confirmed that the aritst was legally blind in his right eye and only had a tenth of his sight remaining in his left. Only one recourse remained: eye surgery, a treatment he had been avoiding with hostility since his first diagnosis. The artist was terrified of the surgery. He was there when his friend and contemporary Mary Cassatt’s cataract surgery ruined her career, rendering her completely blind, never to pick up a brush again.

With nothing left to lose, he finally relented and underwent a series of grueling operations. After an arduous recovery, now in his 80s, Monet returned to his commissioned water lily paintings, beginning a new reinvigorated phase of his career in the twilight of his life. But as fate would have it, the operations had not only restored his vision, but enhanced it by unlocking part of the ultraviolet spectrum.

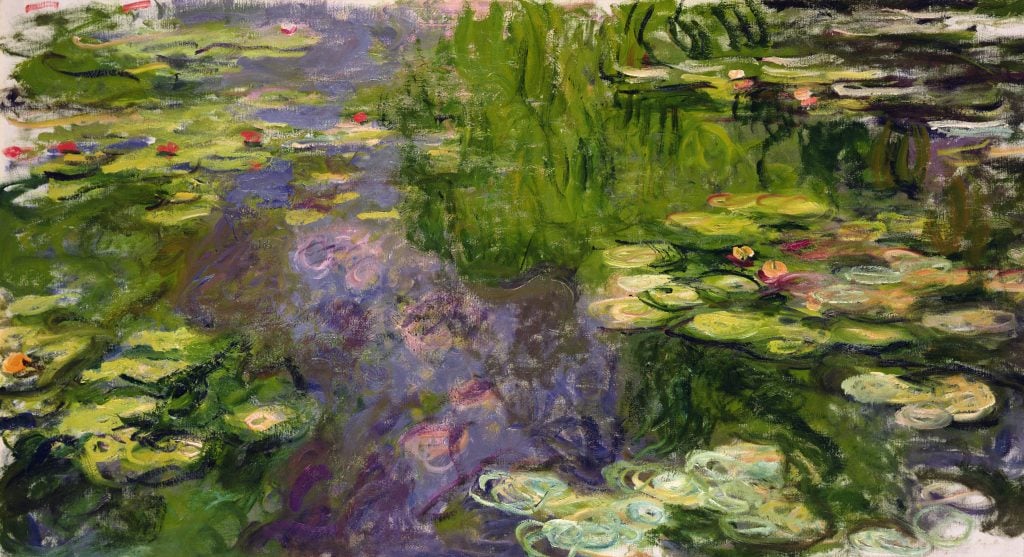

Claude Monet, Water Lilies (1915-26). Photo: VCG Wilson/Corbis via Getty Images.

Human beings have photoreceptor cells in our eyes called cones, which are responsible for color vision. The three cones in our eyes give us access to the rainbow spectrum of colors, starting at red and ending at violet. Some animals, like dogs, can’t see red like we can.

Other animals, particularly insects, can see even more colors than we can, with access to the color waves beyond the violet end of the spectrum, in the color realm of what is known as ultraviolet. To most humans, ultraviolet light is invisible.

Claude Monet, Water-Lilies. Photo: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

Butterflies use UV to detect hidden spots on each other’s wings that distinguish males from females. Some flowers that appear plain and simple to the naked human eye in fact display a flurry of stripes and spots in UV tones that attract bees and other pollinators. This is why ultraviolet hue is known as “bee purple”.

Monet’s ophthalmological surgery did not give him new cones, rather it removed the lens of his eyes, which normally filters out UV light, obstructing humans from detecting it. So, at 85 years old, Monet’s magnificent eye gained access to the secret world of bee purple.

Clause Money, Irises (1926), is among the last artworks Claude Monet ever worked on. Photo: by Heritage Art/Heritage Images via Getty Images.

From then on, whenever Monet painted the vivid irises of his Japanese Garden, or the water lilies that skimmed the surface of its pond in Giverny, France, his flora radiated an aura of delicate purples and complex indigos. Ultraviolet paint had not yet been invented, so he had to make do.

Claude Monet, The Water Lilies: Morning with Willows (ca. 1915–26) in Orangerie Museum, Paris, France. Photo: PHAS/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

With his eyesight renewed, Monet soon renounced his cataract paintings, rebuking their wild brushstrokes and garish colors. Yet the art world has embraced them as fundamental to the development of art history.

Today, his cataract works are considered as the link between 19th century Impressionism and 20th century Abstract Expressionism. His aesthetic shift, to him a symptom of practical circumstances outside of his control, came to define an era of transition.