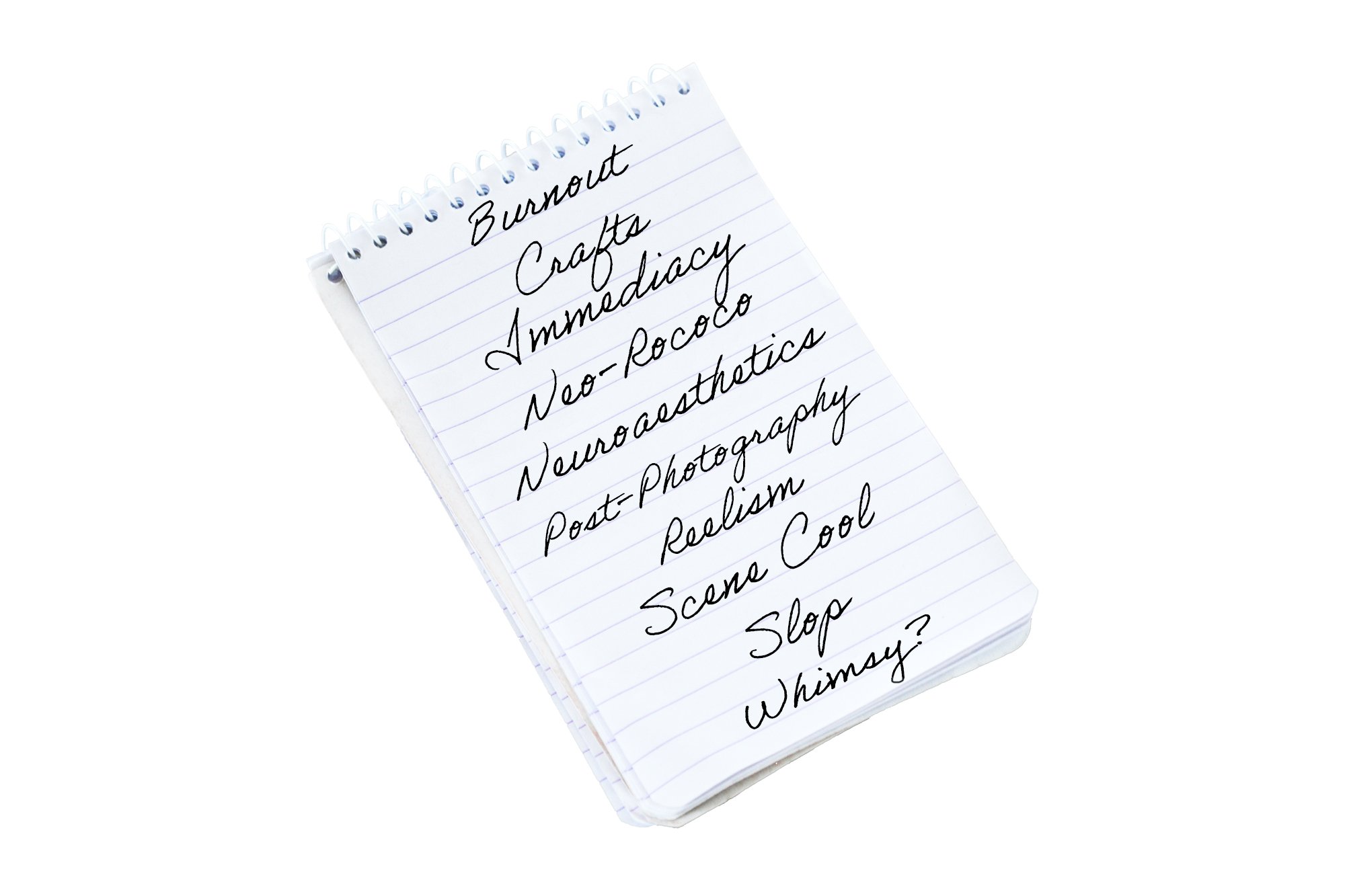

Here we are, shambling to the end of 2024. How to make sense of this chaotic year? Here are a few keywords that were important to the year that was in art, or that provide ways to talk about what it all meant.

Burnout

In a way, this is putting a name on an absence. Looking at the sheer number of crises surging up all around the world, you would think that art would be lit up by them. It was not. Art felt withdrawn from the present this year, full of low-key pleasures, decorous gestures, and carefully calibrated acts of retrospection.

“Activism” was a hot topic in art following the election of Trump back in 2016. By now, “crisis fatigue” and cynicism have set in, social justice is in retreat in the broader culture (as the Economist sought to prove empirically in September), and the Resistance has yielded to the Retreat. The U.S. election hardly registered as an explicit topic in art this year. The singular exception to the falloff of political energy was the urgency of pro-Palestine activism, which percolated everywhere, even as it was suppressed.

Published this year, Hannah Proctor’s book Burnout: The Emotional Experience of Political Defeat is well worth reading in this context, both to get a sense of the moment and to cope.

***

Crafts

Installation view of “Beyond Patchwork: The Abstractions of Yvonne Wells” at Fort Gansevoort. ©Yvonne Wells. Courtesy of the artist and Fort Gansevoort, New York.

“Craft,” of course, is not a novel or a new word. Maybe that’s fitting, though, since a grounding in tradition is the point.

For novelty’s sake, I almost went with “social craft,” my personal term for forms of contemporary art that celebrate the materiality, community, and processes of traditional crafts, but that actually function more like installation art—what you might associate with artists like Marie Watt or Suchitra Mattai, who had big years.

But the truth is that the big thing is just craft in general, of all kinds—art craft, studio craft, anything that evokes a tradition of craftsmanship in respectful or modified form. The Venice Biennale was full of textiles, from the traditional to the experimental. Textile art was all over the galleries and the museums (we did a podcast about this). Pottery and ceramics are everywhere too. For that matter, basketmaking is big—see Jeremy Frey’s lovely baskets at the Art Institute of Chicago.

***

Immediacy

A view inside “Frida: La Experiencia Inmersiva” at the Foro Folanco in Mexico City. Photo by Ben Davis.

Anna Kornbluh’s book Immediacy, or The Cultural Style of Too Late Capitalism (2024) argued that a drive toward direct experience was key to understanding the mutation of culture in the recent past. More than that, working in the tradition of theorist Fredric Jameson (who died this year, R.I.P.), she speculated that a number of dispersed cultural phenomena, from autofiction to Immersive Van Gogh and its ilk, could be read as cultural symptoms of a sped-up consumerist economic order defined by one-click shopping and just-in-time production.

ArtReview’s “Power 100” list voted Kornbluh the ninth most powerful person in art this year on the strength of the book—which is, to be honest, a little much (though that list is always eccentric). Nevertheless, it shows that “immediacy” and Kornbluh’s related idea of “immediacy style” has touched a nerve.

***

Neo-Rococo

Anne von Freyberg, SUN KISSED (AFTER FRAGONARD, VENUS WITH DOVES) (2023). Courtesy of the artist.

Sensual, frivolous, unabashedly femme—a Rococo vibe is back, as my colleague Katie White wrote. The very popular British painter Flora Yukhnovich is the flagship name, directly channeling Rococo themes, as well as Michaela Yearwood-Dan. I also think of a figure like Yvette Mayorga, with her hot-pink works decorated like cakes, made in some cases “after François Boucher.”

In art history, the classical Rococo/Late Baroque era was always rooted in an overripe leisure class. It resonated beyond its time, as John Berger once speculated of Watteau, because of its ambivalent energy that seemed “partly a nostalgia for a past order, partly a premonition of the instability of the present, partly an unknown hope for the future.” You can see why it would resonate.

***

Neuroaesthetics

Monica Aissa Martinez, Thought Patterns (2024). Courtesy Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art

Last year, the book Your Brain on Art: How the Arts Transform Us made ripples. This year, the American Alliance of Museums teamed up with the International Arts + Mind Lab Center for Applied Neuroaesthetics to make the case for the “profound nexus between arts and culture and societal health.” In Arizona, the Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art’s staged “Brains and Beauty: At the Intersection of Art and Neuroscience,” with the Penn Center for Neuroaesthetics, which, across the country, also drew attention for its artist-in-residence program, hosting stained glass artist Judith Schaechter. Heck, the hotel brand Design Hotels was touting “neuroaesthetics” as a trend.

What this amounts to, I’m not totally sure. Does making a psycho-biological case for art experiences improve public engagement with them? Is it a bit like explaining a magic trick? In some ways, the uptick of institutional interest around “neuroaesthetics” feels like the humanities trying to claw for legitimacy as tech steamrolls everything else. At any rate, expect to see more people with electrodes strapped to their heads in the galleries.

***

Post-Photography

Boris Eldagsen, The Electrician (2022). Photo courtesy Boris Eldagsen.

This is a term that has mutated. A decade ago, people were talking about the “post-photographic condition,” referring to how ubiquitous smartphones and digital media had changed the medium of photography. More recently, “post-photography” is back in circulation to explain a new development: art images that are meant to look like photos but are made with A.I. That’s how the term appeared, for instance, in “Post-Photography: The Uncanny Valley” at Palmer Gallery in London, which included Boris Eldagsen, who tricked the Sony World Photography Award last year with an image made using A.I.

***

Reelism

View of Anna Uddenberg, Continental Breakfast, Meredith Rosen Gallery, New York, 2023.

The term for a performance artwork made to fit the format of Instagram Reels or TikTok, favoring looping living tableaux. Anna Uddenberg’s Premium Economy, a performance that involved women mounting surreally designed airport chairs that then lifted their butts into the air, at this year’s Art Basel, is a great example—but Kate Brown has a whole article looking at examples.

***

Scene Cool

Haliey Welch appears at SiriusXM Studios on July 31, 2024 in Los Angeles, California. (Photo by Michael Tullberg/Getty Images)

This is trendcaster Sean Monahan’s term (or the term of his “twentysomething friend Blair,” to be precise.) It is the opposite of “internet cool.”

Ten years ago, Monahan helped coin the term “normcore” with the collective K-Hole. That trend was one symptom of the end of the hipster era of coolness-as-obscurity. That moment seems, in turn, to be sunsetting as well, as the spiral twists backwards towards scenes and obscure knowledge again—or at least towards a suspicion of virality. As Garbage Day put it, referring to the dubiously bankable cachet of the online phenom known as “Hawk Tuah Girl,” “virality is decoupling from popularity.”

Another clue pointing in the same direction, trend-wise: the big interest in the Dark Forest Anthology of the Internet, published by Metalabel this year, which theorized the cultural effects of the turn away from online visibility.

***

Slop

An A.I.-generated image of a lightning bolt, posted to the Facebook page “The Space Academy.”

Probably the single most important new word of the year for culture. An outgrowth of “spam” and “digital kitsch,” it’s the word for the bulk production of low-quality text, image, video, and audio content by generative A.I.

One of its main characteristics is that you cannot escape it. So I wrote about it a lot this year, whether in its pure form as produced by “sloppers” on Facebook making fake nature content or as it manifested in Google’s sloppy collab with artists to make an ill-thought-through A.I.-generated version of Alice in Wonderland.

The term can be abused. Not all art using generative A.I. is slop. But the very fact that that caveat needs to be made shows that slop is one of the byproducts of A.I. that any art made with the technology is going to have to wrestle with.

***

Whimsy?

François-Xavier Lalanne, Troupeau d’Eléphants dans les Arbres (2001). Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

“So, the thing now post-election appears to be… whimsy?”

That’s what an artist friend of mine observed coming back from Art Basel Miami Beach. Well, the Miami fairs are never the most high-flown, but you can see how an air of mildly surreal irreverence might mediate the tensions running through art right now. It’s an alternative to the earnest, self-serious, and didactic, but also to the placid, decorative, and bucolic vibe that a lot of art has fallen back into.

It was whimsy that sold at the auctions, as the New York Times noted. Not just the curdled whimsy of Maurizio Cattelan’s banana, a.k.a. Comedian (2019), but the playful design of Les Lalannes. There was a bit of whimsy in the “relational aesthetics” revivalism of the Beyeler Foundation’s summer show. And the term also fits a breakout emerging artist like Louis Osmosis, who drew chuckles at the Armory earlier this year with paintings featuring irreverent little quippy cartoon characters.

***

Y3K

LuYang, Digital Descending, ARoS, Aarhus, 2021. Exhibition view. Courtesy LuYang and Société, Berlin.

A late breaking addition, but I’m gonna throw it in! “Y3K” was among Google’s most-searched “Aesthetics” this year (a term that has itself taken on a new life in recent years). However, while other trending Aesthetics like “Mob Wife Aesthetic” or the “Airport Tray Aesthetic” do not really have any correlate in art, Y3K does.

It’s a spin on Asia-Futurism (critic Dawn Chan’s term), filtered through the kind of late-’90s futurism of Missy Elliot videos and re-processed through K-Pop glam. It’s got some cachet in fashion and beauty (e.g. “smart nails“), but Jing Daily also sees a Y3K vibe in the music-video-like digital worlds of an artist like the Shanghai- and Tokyo-based LuYang, whose film DOKU The Flow (2024) was at Fondation Louis Vuitton earlier this year. In any case, fashion-y futurism abounds.