My dear departed friend Ted Rousseau, my second-in-command at the Met, had once joshed, “There are two breeds in the world, Connoisseurs and ‘Konnoysers,’ Tommy, and we are the epitome of the former.”

Not long before my TV career was beginning to falter I received a phone call from Gilbert Maurer, the president of Hearst magazines, who wanted to meet me with his boss, company president Frank Bennack, and chat me about a matter of “mutual interest.”

Maurer was a blond, distinguished-looking, slightly pixie-faced gentleman in his early sixties. Bennack, dressed elegantly, looked like a retired stevedore who had made it big in Vegas — very slick and rough at the same time. Maurer did most of the talking.

They wanted me to become the editor of Connoisseur magazine, which had started in England in 1901 and which William Randolph Hearst had bought in 1927, primarily to have a vehicle to run ads to sell the art junk he had vacuumed up across Europe and no longer wanted. The idea was to bring the magazine, which was fading away, to the United States and with the Hearst marketing genius (“Look what we’ve done with Helen Gurley Brown at Cosmo!”) take it to the stars — meaning high circulation and lusty ad revenues.

I told them both I knew nothing about the magazine world and hardly ever subscribed to or even read magazines.

“Better yet. We want new blood, new thinking. We want you to do with Connoisseur what you did to the Metropolitan — get people to become interested in art. Here’s a suggestion. Make for us a ’Green Book,’ industry jargon for a composite year of editorial. Just jot down what you would like to see each month, for, say, six months and then let’s talk further.”

I concocted the dummy magazine with four features, three columns and a bunch of service pieces — auction prices and the like. I concentrated on hard news as well as the standard art coverage and emphasized writing about what was going on behind the scenes. What does it take to mount a great exhibition? Or a day in the life of a paintings restorer. Or the best American collectors. My definition of a connoisseur was someone who distinguished quality in every walk of life.

They liked the presentation and asked me to become the editor-in-chief of the moribund magazine. An appropriate staff would be selected by the Hearst pros. The pay would be, I thought, astronomical, a quarter of a million a year plus reasonable expenses. I could continue to be arts editor on 20/20.

January 1982 was my first Connoisseur and the cover story was the rediscovery of the “Crown of the Andes,” a florid gold decoration festooned with 453 emeralds. It dated from the 16th century through the 18th and once sat atop the head of a wooden statue of a miracle-making Virgin in a church in Popayan, Colombia, the only building in the village to be spared in a devastating earthquake. I got my pal Lee Boltin who had taken the King Tut photographs to shoot the gigantic piece of golden church furniture and the cover was a knockout.

In an editor’s note, I explained, “I don’t think The Connoisseur conforms to the easy definition anymore than the real life connoisseur does. I don’t believe he or she is elitist or arrogant or snobbish. And I doubt if he even has to be wealthy. The true connoisseur has a special attitude, one that has to do with aspiring. I’m convinced that popularization is compatible with quality when it’s done well and honestly. I also think that good scholarship is compatible with good journalism. This is going to be a ’how to’ magazine for the discerning collector and an encouragement for those who haven’t yet got their feet wet. We’ll be candid. Connoisseurs don’t want any rigmarole. We will state what we think — connoisseurs always have.”

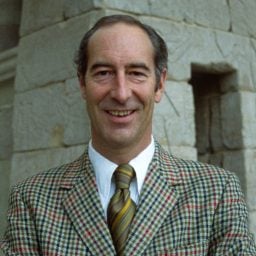

Hearst suggested a gifted young editor, Philip Herrera, as my second-in-command. Phil, a Guatemalan from a land-rich family, had been educated at Harvard and had edited several Hearst star-ups. He was a handsome, short “Mayan,” as a friend dubbed him, quick-witted, sage and lively, one of the most well rounded individuals I’ve ever met. His impression of Nancy and me, I learned later, was that we were “upscale Bohemians.”

Philip became the executive editor and brought on a group of top professionals with whom he had worked for some years. Leslie Smith, an astute and unflappable leader, was our managing editor; Margaret Simmons was the associate editor with a fat Rolodex of writers. Member of her team included Joyce Pendola and Sharon Proctor. Patricia Lynden was senior editor and Judith Sonntag was the invaluable copy editor.

Hearst gave me the art director who was working in their start-up division, Rene Schumacher, a volcanic Frenchman who was also a painter. The publisher, or the man responsible for obtaining advertising, was B. William Fine, a lanky, self-described “New York City born smart-ass” with a heart of gold and a whip of a mind. Bill had an unfailing nose for what was “hot” and had an ability to hypnotize potential advertisers. Bill, sadly, lasted less than a year and was replaced by David McCann, a more mature man whose fire-in-the-belly was waning. Thankfully, he brought along with him a firecracker by the name of Polly Perkins, a captivating, energetic, highly intelligent blonde who single-handedly saved our advertising ass for years with the help of her associate, Brenda Saget.

We worked ourselves to exhaustion for the first American Connoisseur of March 1982. We had no bank of stories. In those frantic weeks, I had an amazing stroke of luck. Patricia Corbett, an American writer who lived in Paris and Rome, popped in to have a word. She was a physically stunning young woman — “saftig” as the Germans would say — with a soft, perfectly proportioned face that made her look, I thought, vaguely like an intellectual Betty Grable. Patricia had an air that engendered total trust and I hired her immediately as a foreign correspondent. She turned out to have incredible contacts in the art world and an unquenchable zeal to pursue hot stories even if they might be dangerous to her health. Her French was Parisian and her Italian, Sienese. In our first ten minutes she landed me the cover story for our first American issue, a series of newly found and unpublished Pompeian wall paintings. Our cover showed a bold painted theater mask of the first century B.C. staring out with wide eyes and an open mouth.

I wrote a major article entitled, “I LIKE ANYTHING THAT MAKES MY BLOOD RUSH,” a profile of a secretive New York City art collector. As my lede put it, “His name is unfamiliar; his fortune relatively modest. Slightly over middle age, of a little more than average height, he does nothing to call attention to himself. If you spoke to him you would be struck more at first by his professorial demeanor than by any crackling energy. This man may be muted, but he burns with a passion. He owns one of the most diverse art collections in America, a collection containing over 2,000 works spanning 20,000 years.” He’d built up his collection primarily from scouring obscure estate sales and, among other treasures, had found an El Greco Christ the size of a playing card, a Titian portrait and an early Sandy Calder necklace.

We commissioned an in-depth article about the Metropolitan’s new Rockefeller Wing, a piece that people considered scandalous because of its candor. It even slammed me for my “dictatorial” management of the museum. I loved it.

How I hated the look of my first American issue! The inept Hearst printers had mangled wrecked the color and some typeface looked blurred. It took months to get the book looking bright. I should have realized right then that, despite all the upbeat talk from Maurer and Bennack, their hearts were not in making Connoisseur a success.

Pat Corbett landed another great story, the first views of the cleaned Sistine ceiling. I put a detail of Eleazar’s face from the niche containing the figures of the prophets Mathan and Eleazar on the cover. The detail was precisely life-sized.

I was invited to see the completion of the cleaning and ascended a rickety elevator to the vault — which rises only five inches, not the yards and yards it seems to — and cleaned a portion of the Separation of Light and Darkness with a pristine sponge. One wipe, the mostly coal dust of centuries disappeared and I saw a fresco as fresh as the day Michelangelo painted it. I had defended the cleaning project several times in the magazine against the rants of those who claimed the frescoes had been destroyed by the cleaning.

As a lark I wrote how I would go through the entire Louvre in fifty-six minutes flat, showing my favorite treasures and printing a map of my footsteps. It became one of the most-asked-for articles in the entire magazine. I still get requests for it today. My point was not only to de-mystify the place, but also to urge visitors to cut to the chase and look only at the best of the best.

In September, Bill Fine moaned, “Book doesn’t look good enough yet. We’re not moving anywhere near fast enough. You ought to splash your name and feisty way of looking at things in a monthly column. You are so outspoken! I can sell this book better if it has a strong, really crazy-strong voice.”

I started a column that was called “My Eye.” Sometimes I teed off, like my “thumping” letters for the old Mirror. I began right away with a slashing attack at my Egyptian colleagues for having wasted so many opportunities to fix up the Cairo Museum. Maurer was enthusiastic. As he told me, “Hoving, nothing’s better than having your own bully pulpit. But don’t forget sometimes to blow in their ear. You know, seduce the philistines.”

That remark made me nervous. I was for solid journalism and the singling out of what was not phony, hyped or Mickey Mouse in the world and he was after blowing in their ears.

For one Christmas issue I visited the top art dealers in New York, London and Paris and “bought” their best of the best. They showed me their top works, ranging from an ancient Assyrian tile through a 2nd century Roman head to an exceptional Shiva of the 14th century to a heavenly Fragonard and a grim but good mural by the Swiss artist Fritz Glarner once owned by Nelson Rockefeller. I “bought” three and a half million worth of treasures to put under the tree. Several of the dealers sold their work because of the piece and we picked up a spate of ads.

I wrapped up my first year in the magazine trade feeling energized about the future of my Connoisseur but depressed about the slow-footed Hearst organization.

“But, hey, isn’t the money real good?” my wife exclaimed.

Right, as usual.

The hottest I’d ever been in my life was sitting in a plane at Beijing waiting for take-off for Shanghai in October 1982. There was no air-conditioning and we had been handed out little paper fans, which should have made Nancy and me suspicious from the start. The plane did takeoff, did manage to fly without incident but then entered a holding pattern for over an hour. We learned later that the hold was because our hotel rooms weren’t ready.

My architect friend I.M. Pei had invited us to accompany him on a tour of China for two and a half weeks along with other illustrious souls — the likes of Jackie Onassis, Evangeline Bruce and Marietta Tree. The trip started in Hong Kong and after Beijing would wend on to Canton, Kweilin, Soochow, Hangchow, Xian and Beijing. The end of the grand tour was to attend the opening of I.M.’s new Fragrant Hill Hotel north of Beijing.

China was bustling, sometimes filthy, and primitive. The people were gorgeous-looking — thin, alert, and healthy. After that wretched plane we traveled in luxurious wide-bodied trains that swept through the ancient land, making the scenes look like an unfolding Ming scroll. Or in buses, a barge and the occasional Chinese limo (a refitted old Soviet Zis that looked like my old Packard). We were one happy gang in our bus that had a toilet (a very primitive one). Once poor Jackie and Evangeline Bruce were “kidnapped”by the local authorities and put in a Zis town car since they were such lofty VIPs. We passed them in our bus and they came straggling in an hour after us, moaning that they’d never partake of that honor again. We stayed in the “finest” hotels and a few dilapidated guesthouses. In one of the latter, I found a black men’s sock under my bed and was told that Henry Kissinger had been in the room shortly before. I failed to take it with me and cherish it, for I considered Kissinger a war criminal.

One high point of the trip was seeing the mountains in the Li River valley. We took a river tour in a lavish barge, being towed through the twisting river by a tug tethered a hundred yards ahead to prevent the engine noises from disturbing our serenity. The ancient landscape was as full of mountains as the moon of craters. I had always thought that the fanciful sugar loaf, hairpin shaped mountains in southern Song paintings were make-believe. But, no, they are real mountains. These were undersea mountains, not the alpine push-up types. For the Li valley had once been an ocean bed, The trip was just as the twelfth century poet Guo Muruo had described the Li Valley, “Oh, behold this magnificent scroll, the sinuous windings of this jade like belt. . . .”

The excavations at the great tombs of Xian knocked me out, especially since our privileged party could walk down into the ranks of the 6,000 terracotta painted warriors — all almost life size and all supposedly portraits of the late army. They were deposited in a pit fifteen feet deep, 600 feet long and 180 feet wide.

Pei’s Fragrant Hill Hotel was a gem thoroughly hated by the Chinese who had commissioned it. It had only 325 rooms but they were as elegant as any modern Hong Kong extravaganza and the atrium was a stunning enclosed space with a glass ceiling hovering one hundred feet in the air. For Pei such a modest job was worth it because he could work in his country of birth and because he wanted to be, “a hinge of fate, the opportunity to find the Chinese character in architecture, to come up with the right kind of uniformity, something akin to the concept of the Georgian style, a style in which any village can be built.”

Everything in our room either didn’t work or fell off when you touched it. At least they’d cleaned the toilets, for the construction workers, never having seen a toilet before, hadn’t flushed them for weeks.

The construction crews had been vying to sabotage as much of the project — and us — as possible. The Scottish engineer who had designed a special boiler furnace for the local soft coal told me he’d almost been killed when someone triggered the switch to start a death-dealing rain of coal when he was temporarily locked in the coal chamber. He only escaped because he knew where the emergency button was located. Once when I sat down on a couch in the atrium, I felt a strange something underneath and found underneath the pillows a dagger-sharp trowel pointed towards my butt. I saw workers deliberately slam stepladders into the modern paintings Pei had ordered from a Chinese abstract painter living in Paris.

Pei felt depressed about the hotel’s future. The manager had been selected, he told me, “Because he was on the Long March with Mao. His duties seem to be mainly picking his nose. Frankly, I have severe doubts that they can manage it.”

They didn’t. The radiant little Fragrant Hill with its traditional Chinese forms and twisting, sinuous gardens never opened. In time it was bulldozed. The anti-hotel cadres had won out. It graced our cover nonetheless.

Once I hired a new art director, circulation soared from the tens of thousands to one hundred and fifty thousand. She was Carla Barr, a sweet-looking cherub with a heart of titanium when it came to design. Our relationship was always touchy, for we both had humongous egos and both wanted to be the lords of our respective universes. Despite some tantrums on each side, we worked fruitfully for together for four years. Then she quit at the time when the Hearst bosses began to insist on downscaling the magazine to increase newsstand sales.

Carla Barr’s first issue hit the stands on April with a provocative cover showing the profile of a pert-nosed, pouty-mouthed model behind some magnificent antique black lace. Old — and new — lace was roaring back into style with fashion’s “old master” Geoffrey Beene coming up with a sensational lace tunic in lilac, which we draped over our lovely.

For July 1983, which was not a big ad month, Carla and I decided to go a bit kooky. I had been pitched a story on Panama hats and the craftsmen in Ecuador who made the finest ones, so dense that they could literally be rolled up and stored in a tube much like a fine cigar for years without crinkling. The writer and photographer of the article, Tony Brandt, had dished up a marvelous story with a list of sources and prices. For the cover, Carla had Tony place the silkiest, pure white, perfectly blocked hat with its spare and very elegant black string band on a spray of fresh dew-dappled palm fronds. It was arresting, but Hearst president, Frank Bennack growled, “Why put a Panama hat on the cover?”

“Because I was entranced,” I answered.

That was another sign.

In August it was suggested by Gil Maurer that I might hire for our fashion pieces the attractive, fashion-model-look-alike Kathleen Hearst, the wife of John “Bunkie” Hearst, who worked somewhere in the family business. She came to our dilapidated offices wearing a sheath designed by the trendy Azzedine Alaia and looked only slightly out of place among the jeans and chinos. A few years after she arrived she invited me to lunch and abruptly asked if I would resign so she could be named editor-in-chief. I decided not to tell the beauteous, but untalented, Kathleen that her qualifications were nil, and politely declined.

Another sign that they were after me.

At one of the annual editorial lunches held usually in the Remington Room of the 21 Club, I was seated next to Helen Gurley Brown, the legendary editor of Cosmopolitan. She looked almost transparent from an abundance of cosmetic surgery, but was witty and perceptive. My novel, Masterpiece had just been published and she asked me to brief her on what novel writing was like. “Shit,” I recall saying. “Harder than non-fiction, for you have to invent the universe every day.”

We chatted about the goals of Connoisseur. She told me bluntly, “You have a special problem, Mr. Hoving, for you can never do what I do every month — you know, how to slim down by eating burgers or the sexiest moves of men or how to be a better blonde or what make-up will make him sweat with joy, stuff for true addicts — but you focus in on the elegant and timeless and I am not at all sure many people are addicted to that or that you will sell in the long run. But, hey, just as long as it sells enough to satisfy the masters.”

Canny lady! I wondered how long I was going to last.

We kept mixing up fine arts and a little fashion with arty jewelry and travel pieces that were quite different from the travel books. We picked only the finest places and when we didn’t like a hotel or restaurant, we said so. For the fine arts, I picked what I believed to be the top 101 art collectors in American history, a piece that was picked up by much of the press and by Liz Smith, the genial gossip columnist of the New York Post. My top collector was the Mellon Family and especially the courageous Paul who virtually single-handedly enormously enriched the National Gallery. The bottom of the heap was my old buddy J. Paul Getty. “A special place just off the list goes to Getty for his infinite promise and mediocre delivery. With his bucks he could have had it all. But too often, he happily bought famous signatures, perfectly content with the second or third-rate paintings to which they were attached. . . . Getty’s case shows what can happen when a man with little taste or real enthusiasm takes up collecting because it is the Thing To Do.”

It was the first skirmish in the war that would eventually break out between me and the Getty Museum.

I was still sailing and skiing as much as I could and had taken up biking on a series of fancy racing bikes, dressed in Tour de France costumes and strap-in bicycle shoes as well.

I may have been — and still am — a risk-taker in my art and business lives. But when it comes to sports I like to describe myself as a “cowardly daredevil,” since I always know my limits to the millimeter. I become an obsessed bicyclist halfway through my Met years and rode madly on a succession of racing and track bikes for the next twenty years. I also plunged into the world of motorcycles, starting with a small Honda, which I used to commute from the Village to the Met or The Cloisters and ended up with a fast and sleek 350 cc. special racing Honda. I had several near misses but always managed to keep my machines under control — once the motor on a tiny bike locked tight and I twisted and skidded back and forth across the West Side Highway for a quarter of a mile, but no car was behind me.

On Quaker Hill I’d bike ten miles a day up and down some chest-wracking hills. I used my breathing style perfected at Eaglebrook when I was almost winded and it still worked. When in the city, I would do a turn of Central Park every day unless the weather was dangerous. I reveled in using the roads I had closed — for the Parks department eventually shut down an entire lane for bikers and, except for the cabbies enraged at the parks closing who would try to run me off the road which happened several times, it was safe enough.

On morning I was going north coasting down the 108th Street hill, listening to a new tape, Philip Glass’ The Photographer, and didn’t notice a squat walker in a blue hooded jacket who suddenly blocked the bike lane. I screeched to a stop and I saw a young black with an expressionless face in front of me holding a snub nosed revolver. I pulled my foot out of the toe clamp and got off.

I did everything I wasn’t supposed to do. I looked him in the eye. I talked to him, for I heard a bunch of cars starting to come down the hill and I figured if I could stall for time he’d run away, frightened by the traffic. I told him he could take the bike even though it was kind of tall for him. I asked if I could remove the contents of the utility bag I had attached to the handlebars.

“Take the shit, man, but hurry.”

I took my stuff as slowly as I could.

He waved the revolver in my face.

Was it loaded? I had no idea, but I made myself look as if it didn’t worry me. I couldn’t imagine this idiot shooting me for a five-year-old bike. What I didn’t really feel was that all my back muscles were locked and straining, though I tried to look casual.

The cars were coming closer. He shot a fearful look in their direction and with a struggle got on my bike. He coasted because he couldn’t reach both pedals.

I was tiptoeing down the road in my toe-clip bike shoes, dressed in my Tour de France outfit, the one with “Cinzano” emblazoned on the front of the Lycra shirt, when a radio cab pulled over and someone asked, “You okay, pal?”

“That guy down there with the bike just stole it from me!”

One of the three airline pilots in the car said, “We’ll get him.” After the robbery I suffered back pains for weeks and finally, on a sail boat cruise in the Virgin Islands had to be taken off our boat on a stretcher and fixed by an alert doctor at the hospital in St. John’s who recognized I needed no surgery, only rest.

The thief dropped the bike and scrambled up the steep hill at 110th Street and into the thick trees. The radio cab stopped and one pilot tried to pursue the kid.

I tippy-toed my way to my bike, which looked undamaged. “Did you see him? Did you see his gun?”

“Gun! You stupid bastard, asking us to get some guy with a gun!”

The pilots piled back into the car and took off.

The afternoon of Bill Clinton’s victory party in 1992 I was biking through the 79th Street transverse drive and my front wheel ran into a two-foot-deep hole covered with still water. I flipped, ripped my face open and broke several fingers on my left hand. But I managed to drag myself and my bike away from the cars that were coming right after me and which missed me by inches. I was never so close to death. As I carried my bike home, people pressed against the buildings to avoid the bloody mess. But, with a thick application of the right antibiotic goop, I was fixed up sufficiently to attend the victory bash.

In my sailing ventures I had a few near misses, all of which energized me. On one memorable New York Yacht Club cruise from Newport to Maine we were to race from Marblehead to Rockland, a course that would take us some seventy-five miles off shore. The start was put off several times because of calm winds and finally towards dusk, we got under way. The wind picked up gradually until it was blowing directly downwind some forty knots — a challenging breeze. Direct downwind is probably the most dangerous point of sail, for any miscues on the part of the helmsman can cause a knockdown or sudden broaching resulting in dismasting and if not that then the blow-out of the spinnaker and every sail forward. Not only was it blowing like hell, but also a heavy fog had developed. We poured on more sail and put up preventers to avoid any sudden jibes of either the spinnaker or the Genoa.

In the waning daylight we sailed through a fleet of a dozen smaller boats going the opposite direction with everyone shrieking, “Right of way!” That we didn’t smash into any of them was a miracle. Then, when it got dark and really foggy, we suddenly encountered a huge fleet of immense vessels studded with searchlights. What was this! We had sailed right into the middle of a fleet of Russian trawlers and their canning factory ships and had to work like hell to maneuver around them, at the same time keeping from jibing or broaching. At three in the morning, somewhere in dense fog off Maine, I was on the foredeck as waves broke over the deck — I was in three feet of blue water, trying to salvage the ribbons of the fourth of four spinnakers that had ripped to pieces.

A crewmember shouted at me to get my ass below, the skipper wanted to see me. There was a deathly white, wasted Danforth Miller, no longer the tough, deeply tanned master. He was suffering severe chest pains with spasms down his left arm. It was a heart attack and a bad one.

Feeling I had to look cool, I told him to relax, “I’ll take over, we’ll win the race, and, shortly I’ll be back with a sharpened kitchen spoon, a guttering lantern and the tide book which, I hope, has basic instructions for open heart surgery.” He made it, possibly because I took his mind off his plight.

I broke up with Captain Miller after some eighteen years with him. We were sailing out of beautiful Hadley’s Harbor near Wood’s Hole with five or six other sailboats on our way on a New York Yacht Club racing cruise through the most dangerous passage in the Northeast, the Woods Hole gut (where freight-car sized buoys are often sucked under by the racing tide). The young son of one of the permanent crewmembers was at the helm. I was below editing a chapter of my first book — on King Tut — when the boat stopped dead from a speed of five knots. I was thrown against the forward wall and had my wind knocked out. A very large, very sharp carving knife flew inches past my head from the galley.

The noise from our keel was ominous, a horrid crunching and grinding sound. After a few moments of shuddering, the boat broke free from the rocks. Thinking that we’d sink, I grabbed a garbage bag and put the only draft of my first book inside and tied it around my waist. When I got on deck I could see three other boats that had been close to us smashed on the rocks and staying there, perhaps forever.

The skipper, who had not been paying attention, was furious but seemed to think we had just bounced and would be okay. I disabused him of that by observing that the floorboards were floating around below. We limped out of the passage and a Coast Guard boat came alongside and asked if we needed assistance. I shouted we needed a pump desperately and, by God, they had a gasoline-powered one and humped it over. We limped into Falmouth just before sinking with that pump racing full speed. I told Miller that I’d be willing to pick up a portion of the expenses, say, three gees, because it wasn’t the boy’s fault, a more seasoned crew member should have been at the wheel, meaning Captain Miller.

When the work costing eight thousand dollars had been done I chartered the Blixtar for a family cruise. We sailed around the Elizabeth islands for a week. Suddenly, Miller called me and said we’d have to return at once; he had a buyer for the boat. We cut off our vacation, raced back and cleaned the boat for four hours like she’d never been scoured in her life, using toothbrushes on almost-hidden mould in the crevices.

I called my friend a day or two later and he blithely told me there never had been a serious buyer. And he was sending me the bill for the entire eight thousand dollars. His wife had told several people who informed me that we had left the boat in “disgusting condition.” I paid a third of the damage and never spoke to Miller again.

My blue-water racing days were hardly over. I signed on with a gorgeous fifty-foot one-design named Katrinka, owned by an enchanting family from New Haven, Frank and Mary Winder. Frank was an architect and had with his talented wife designed the interior of the sloop that glowed with hospitality. The layout below decks was both that of a comfortable cruising vessel and a racing machine. Katrinka’s colors were of the earth, dominated by delicate and pleasing rusts and mellow reds. The woodwork from the smallest details to the entire galley was like fine furniture.

The personalities of the Winders matched the elegance of their lovely boat. Their children and one son-in-law were expert sailors. Everyone in the family was funny as hell and adored good parties. Nancy and I fell in love with the Winder family as did my daughter who, briefly, dated Peter Winder.

When I started racing on Katrinka I was half-expecting a “family” atmosphere, but I got hard, clean, competitive stuff, which was far more organized, and crafty than anything I had experienced on three Blixtars. I accompanied the Winders on a half dozen races in Long Island Sound and two Bermuda’s, plus one dreamlike cruise in the Leeward Islands, from Grenada to Saint Bart’s.

On my first Bermuda with them, a drug company sent representatives to find crewmembers who wanted to try out and keep an accurate log of a new patch that one put behind an ear that prevented seasickness. I signed up only because I had been felled several times and hated getting sick. The drill was for me to apply the patch only at midnight on the third day out. I had to record how I felt before and after and if there had been any change.

That year the start was delayed a day or so because of a hurricane passing near Newport and for the first three days out the seas were monstrous rolling waves. I was stricken and could eat only a half banana a day and was weakening rapidly. At midnight on that third miserable day, as instructed, I applied the patch and went to sleep in the upper bunk. A Winder hollering at me to get my wet ass moving awakened me at 3:45. Climbing out of the high bunk, I slipped and fell to the cabin sole five feet down. I blacked out and when I came to, I suddenly felt violent hunger pangs. Not for a lousy banana, but for some real chow. For a day, the remains of cold lasagna had been sitting on the stovetop — everyone was feeling queasy. I donned my foul weather gear, strutted over to the lasagna, grabbed a fistful and then another and gobbled it down. I climbed on deck and raced around, feeling as strong as the Incredible Green Hulk and stood two straight watches amounting to eight hours. My stomach was like steel, my head clear and I sang badly at the top of my lungs. The drug company got a kick out of my report and part of it was printed in the company newsletter.

I quit big-time racing on Katrinka. It was on a second Bermuda race when we got trapped in a storm system that gripped us for three and a half days with a dozen or so squalls in a series hammering through night and day blowing from fifty to one hundred knots. In several squalls, lightning would hit the waters near Katrinka and the sound of the bolts smacking the water was like a telephone pole had been impelled into the water from a hundred feet in the air. We blew out sail after sail. Our rudder chain broke and we had to install a ten-foot long solid steel tiller, making the vessel difficult to maneuver away from a boat near us that kept disappearing as the tops of fifteen foot waves kept blowing off in the hurricane-force winds. Around midnight the third night of this horror, while I was cringing with fear on the foredeck, I lost my nerve.

From that day I never raced competitively again and seldom even cruised. That signaled another one of my personal quirks; once I’d done something or drained something I stopped abruptly and never did it again.

When I got back to the safe mainland, I told Nancy I was too old for sailing since it was too dangerous. I had decided to take up flying.

“To avoid danger, I suppose,” she said.

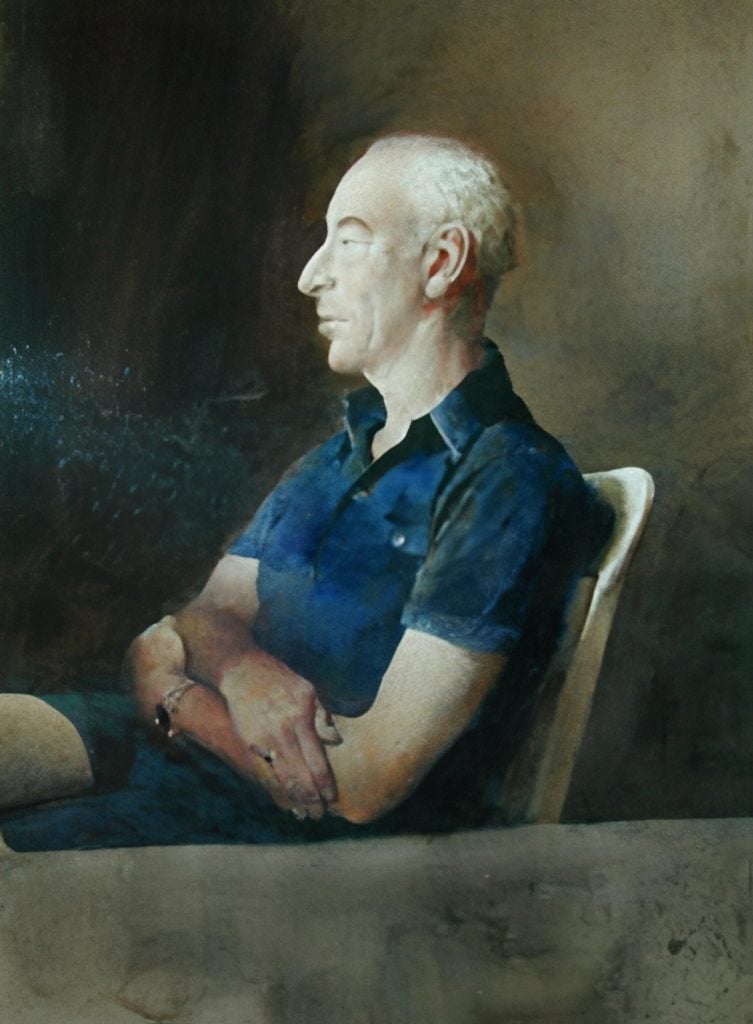

By its fifth anniversary the circulation of Connoisseur had risen to 324,000. Readers told us they liked us because we never failed to surprise. We published an article on the glories of a little-known medieval chapel hidden under the Houses of Parliament; a story on a number of great paintings recently cleaned with profiles on the master conservators responsible (one was John Brealey of the Met who had just finished cleaning Velazquez’ Las Meninas; the work of the reclusive “Rembrandt Team” that had for decades been studying every work in existence and opining which were real and which were outright fakes. I got the Met’s former chief paintings conservator to state that he thought the portrait of Rembrandt’s son, Titus, which graced the cover of collector Norton Simon’s museum catalogue, was a forgery. Simon was not amused.

We did a profile of a budding comedian named Steve Martin and singled out young actor Ian McKellen for special praise. There were profiles on the best “noses” for wines, perfumes and even a legendary connoisseur of fur who looked with his fingers. The fur maven recalled sitting at the Leningrad market, running his hands over hundreds of pelts then suddenly stopping and growling, “Get rid of these last three dozen; you tried to palm them off on me three years ago.”

I concocted a six-day tour of New York City’s museums which had become jammed with works of art because of an early inferiority complex — having nothing when the city was born, its citizens had to have something from every civilization ever known. Achaemenian daggers, baroque harquebuses, wampum by the yard, dozens of real and not so real American weathervanes, Art Deco settees, a medieval silver finger reliquary (fake!) stables of old masters, platoons of Rembrandts, stone carvings from the Maya, Inca and Aztecs, seventeen tons of Paul Manships, hundreds of Limoges tureens, and a lone fur-lined coffee cup (with saucer).

In “My Eye” I had fun bashing what was sleazy. I excoriated the Whitney Museum’s board of trustees for approving a comically bad architectural master plan by Michael Graves. I had noticed that if you turned his design for the façade upside down, you’d see a cartoon-like face of an old geezer winking at you. The plan was killed, I was told, not directly because of my acerbic comments but they had helped. I went after 60 Minutes for blindly following a spurious theory that the Met’s great Georges de la Tour Fortune Tellers was a fake and advised Morley Safer to grow up. I’m sure he did not. I took the city government and the Parks Commissioner to task for allowing Central Park to go down the drain. I wrote a vicious column about the degradation of New York City entitled “Rat City.”

Did we bop around the world! We published a profile of the seigniorial hotel in Geneva, the Richmond, run by the Armleder family. (The concierge at the Richmond was once asked by a guest to help get his kid into Eton and it worked). We covered the spiffy Spa Maine Chance in Arizona. I wrote about the “Best Overlooked Painter in America,” Wayne Thiebaud, he of the cake and pie and precipitous streets of San Francisco. There was even an article on the world’s six greatest staircases. A corker of an article was on the finest mountain guide in Chamonix, who had saved the lives of a half dozen clients in his career.

We ran a piece on where, when and how to see grizzly bears. We obtained exclusive rights to a book by the British investigative reporter, Colin Simpson, proving that the vaunted connoisseur, Bernard Berenson, was on the take from the dealer Sir Joseph Duveen as revealed in a secret accounts book. We profiled the consummate fakebuster of Italy, Pico Cellini, who had unmasked some startling forgeries in Roman museums.

I insisted that the magazine develop tough investigative pieces, especially in the world of art and over the years Connoisseur recruited a bunch of eager, gifted investigative reporters. My favorite pair of investigative reporters were Melik Kaylan and Ozgen Acar, known as The Turks. Kaylan, a Turk who spoke Arabic as well as French and German, wrote a blockbuster of a story on the theft of the tomb where the Metropolitan’s sensational East Greek Treasure, a hoard of over three hundred silver objects of the 5th century B.C had been illegally found. The story included interviews with the thieves who had made detailed drawings of the more illustrious objects — a smoking gun since the Met had never published their treasures.

I eagerly pursued the story because I was pissed off at the Met for breaking a promise with me about the hoard. In the first board meeting of my directorship in March 1967, it was reported that the last batch of something called the “Lydian hoard” had been paid for. This hoard had been supplied by my old friend John J. Klejman, who had dealt in so many illicit antiquities.

When I saw the three hundred magnificent silver objects, I knew that someday they were going to be trouble. Later, when the Turkish government began to pepper us with official requests to return the material, I asked for proof of provenance. The Turkish officials said they were working on it.

I made a pact with my Chairman Douglas Dillon, Dietrich von Bothmer of Greek and Roman, and the man who was then Secretary and in-house lawyer, Ashton Hawkins. “Let’s agree that if the Turks come up with a proven provenance we’ll return the hoard, okay?” They agreed.

But after I retired, when the Turks sent hard evidence that the hoard must have come from a tomb in Turkey, instead of discussing a return, Hawkins and director Philippe de Montebello stonewalled and spent several million dollars on a legal attempt to block any return. They persisted even against the wishes of their boss, William Luers, the museum’s president, who had come close to cutting a deal with the Turks to share the hoard. Luers is said to have been so frustrated when his silver deal collapsed that he quit his post.

Amazingly, in the discovery process the American lawyer for the Turks found an incriminating memo in the Greek and Roman department files from a Met associate curator describing that he had visited the pillaged tomb and had seen the bottom halves of two alabaster sphinxes the proud heads of which were hidden away in the Met’s storage. Although the Turks were willing at one time to share the treasures, this memo triggered a return of the silver to Turkey. Kaylan’s article played a powerful role in persuading the Turkish government to pursue the case.

Kaylan then hooked up with a Turkish reporter, Ozgen Acar, and delivered to me a splendid piece about a giant 3rd century A.D. red-stone sarcophagus from Pergamon, which a private collector was loaning to the Brooklyn Museum and which had been smuggled out of Turkey. I got them going after a hilarious tip I got from a Brooklyn Museum trustee. He told me that when the curator, who had sworn to the board that the sarcophagus had never been in Turkey in its long existence, opened the sarcophagus, he had found several Turkish newspapers inside.

Once we published the facts a hassle over how to get the huge sarcophagus back to Istanbul ensued. The collector said nuts to its return; he wanted a hefty tax deduction on the piece evaluated for eleven million dollars. I got one of my flashes and remembered that a tax-deductible foundation for Turkish-American affairs already existed. Everybody could be happy. The owner of the sarcophagus could give it to the foundation and take his deduction. Brooklyn would be allowed by the Turks to show it for a year and then send it to the Archaeological Museum in Istanbul. There’s now a special gallery in the Istanbul Museum with half a dozen formerly illicit antiquities given to the foundation by Americans who received their tax deductions.

The “Turkish team” of Melik Kaylan and Ozgen Acar wrote about the discovery in central Turkey of some clay jars containing nearly 2,000 silver Greek coins of 465 B.C. — in perfect condition. The treasure weighed fifty-eight pounds, precisely that of an ancient talent, which could buy one hundred and fifty slaves or 1,300 oxen. The current value of the hoard was over ten million, for in the treasure fourteen unblemished, rare Greek ’decadrachms’ were found, worth anywhere from $300,000 to $600,000 each. They tracked the hoard from the moment two Turks, testing a metal detector, had stumbled upon it to its being bought by member of the Turkish art “mafia” and then smuggled out of Turkey into the hands of a numismatics outsider.

This outsider was one of America’s wealthiest citizens, William Koch, the America’s Cup defender enthusiast and a member of the board of trustees of Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. Koch had set up a company, OKS Partners, with Jeffrey Spier (he who had stumbled upon the Getty fake small kouros) and a New York banker who dabbled in purchasing antiquities. The partnership purchased some 1,600 coins for $2.7 million.

While the article was being fact-checked, it disappeared from Kaylan’s office at the magazine. We never knew who took it, but not too long afterwards,William Koch published a long letter in a numismatic journal complaining about inaccuracies in Kaylan’s Connoisseur article, all of which we had corrected in the second draft well before being published in the magazine. That suggests some Koch minion had been sneaking around our offices after hours.

Coincidentally, at the same time, I happened to fly my plane to Plymouth and Provincetown to see a demonstration of an experimental aircraft firing 22-caliber machine guns at rubber rafts. A flying buddy of mine had outfitted his home-built aircraft with the machine guns to try to sell the plane to foreign governments. Only one person showed up for the demo, a man who claimed he had once been an Israeli military man and who asked me to give him a lift to see the show. I was only slightly disconcerted on the way over when he calmly said, “I happen to work security for Bill Koch. We have eyes everywhere.”

Our article made it difficult for the OKS Partners to sell their hoard and I suppose Mr. Koch is still mad at me.

In an antic investigative piece Ozgen Acar managed to obtain a grainy photograph of a splendid marble sculpture depicting the Flaying of Marsyas, the overly ambitious flute player who had tried to compete with Apollo and, having lost, was flayed alive. The photo had been taken by the Turkish farmer who had dug up the piece on his property. We found the sculpture, polished and pert, on a pedestal in Manhattan’s Atlantis Antiquities, a gallery jointly owned by the coin dealer Jonathan Rosen and Robert Hecht (of Euphronios krater fame). Once our story was published an aggravated Hecht gave the piece back to Turkey.

The Turks later found a pair of first century Roman marble legs, cut off at the waist in a museum on Ankara that seemed to belong to a bust of the Weary Hercules on loan from the antiquities collectors Leon Levy and his wife Shelby White to Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. The then curator of Greek and Roman, the crusty Cornelius Vermeule, scoffed. He didn’t scoff when Melik Kaylan pointed out that, from passport records of his travels in Turkey, Vermeule could not have missed the legs in Ankara several times when he was studying in the museum in the ‘90s.

I suggested to Acar obtained that he get a plaster cast of the top of the legs. We puckishly sent it to Boston. It fit perfectly, of course, but curator Cornelius Vermeule resisted any entreaties to send the Weary Hercules back to Turkey. The piece is now back in the private collection of Ms. Shelby White, who loaned it to Boston. She is the widow of the wealthy collector Leon Levy and along with her husband graciously gave funds to help the Met build its shining new Greek and Roman galleries named the Leon Levy and Shelby White Galleries. There are few things that Met director Philippe de Montebello would have liked more than Ms. White’s treasure of four hundred antiquities, but with the Italian government seeking restitution of a number of pieces from Ms. White, he could not accept the Levy-White collection as a gift. But this will work out in time.

Previous Chapter – Next Chapter