Art World Archives

Artful Tom, a Memoir—Off the Charts

Discover the captivating first chapter of 'Artful Tom, a Memoir,' chronicling the extraordinary life of a controversial yet talented art curator.

Discover the captivating first chapter of 'Artful Tom, a Memoir,' chronicling the extraordinary life of a controversial yet talented art curator.

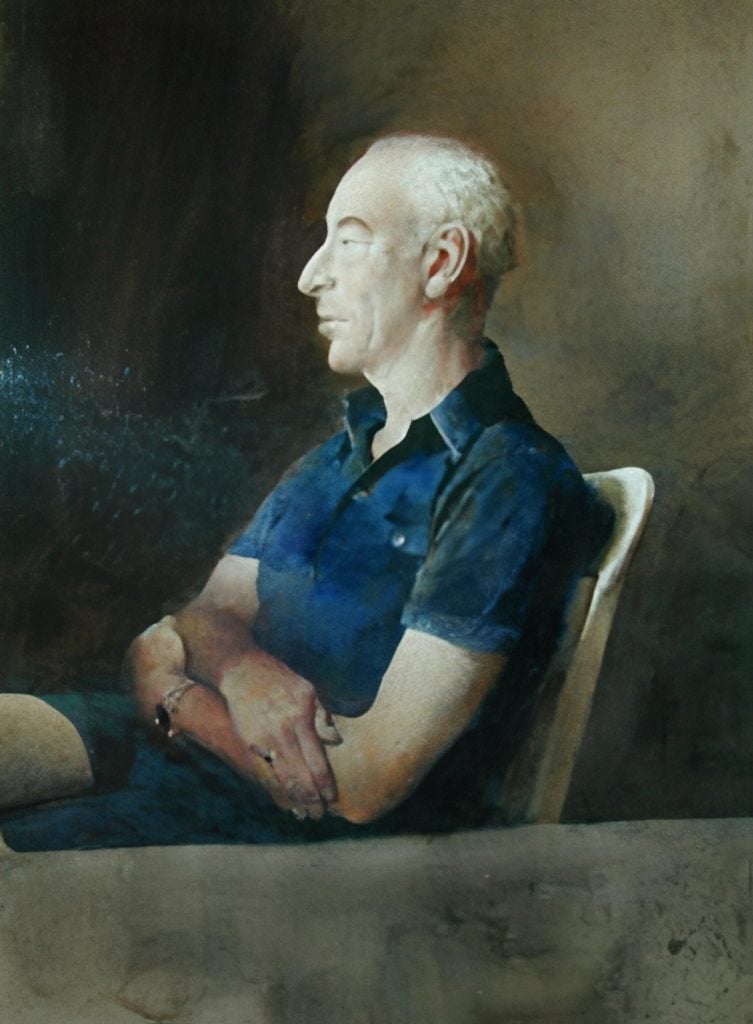

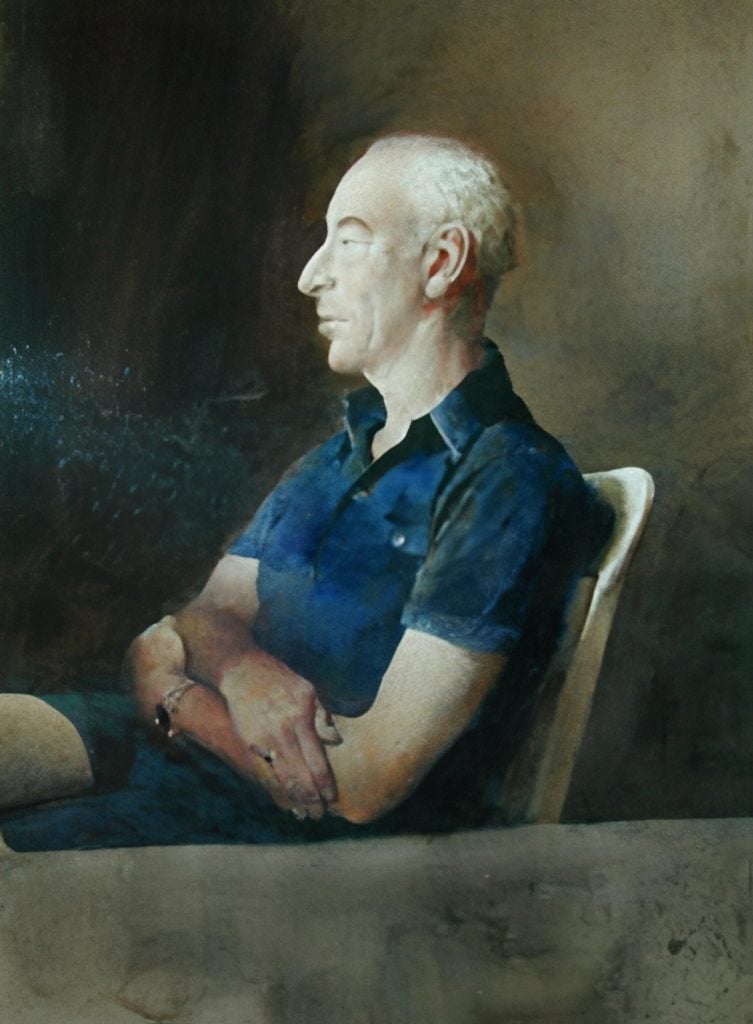

Thomas Hoving

Artnet News is publishing excerpts from Thomas Hoving’s Artful Tom memoir, originally featured in the Artnet Magazine archives, to reintroduce the bold perspective of one of the most influential figures in American museum history. As director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art from 1967 to 1977, Hoving pioneered blockbuster exhibitions and expanded the museum’s global reach, shaping art’s public reception. By revisiting his firsthand accounts, we aim to illuminate the power structures, controversies, and personalities that continue to influence the art world today.

When I was eight my father thought I was a troubled, stupid kid. He sent me to the Johnson O’Connor Institute for Aptitude Research where I was given a battery of tests.

The Institute specialists found that when it came to aptitudes I was off the charts — I had too many. I also scored phenomenally high in visual acuity, detecting quickly what was common in a group of seemingly unrelated objects – that three out of fifteen photos of people had their hands raised above their waist or that five out of twelve objects like a cat, a car, a chair had four legs. In inductive reasoning, I was at the highest level the institute recorded. Deductive reasoners plod along from “A” to “B” to “C.” whereas inductive reasoners dart from, say, “T” to “G” to “Z” to “A” – in a kind of a zigzag. My deductive deasoning skills were lousy.

Years later my father recalled what the O’Connor analyst had told him, “Your son can do anything – or so he tests. He will probably be an amazingly quick learn and have flashes of genuine intuivity, meaning he’ll see tiny things that others don’t notice. He has a fierce ability to concentrate, almost a fixation. People with too many aptitudes tend to be highly active, arrogant and unpredictable. He might be outrageous or solid and sometimes both at one time. That might be glorious or a great burden for him. His life may turn out to be turbulent but it could be exciting with many dramatic swings.”

He might have been right – I have always favored the outrageous, but when I have done something crazy I somehow have always lucked out. Many times in my life I have experienced a sudden flash and recognized that a tiny detail of an object or an issue or a theory that no one else could see had tremendous importance. Sometimes that led to disaster, but more often I triumphed.

For example, in the middle of my sophomore year at Princeton University I was about to flunk out and exams were coming up. To prepare for the crucial midyears, two of my roommates and I decided to pick up a carton of eggnog mix and have one milk punch, then sleep well, then study.

We lived in a stately suite of three rooms in Holder hall, a dormitory historically known for rakes and drunks. There was a fireplace in a large living room was decked out with stained glass windows decorated with Princeton’s Orange and Black seal and its Latin motto, Dei sub numine viget – which I, as the resident Latin scholar, loosely translated for my roomies as, “Under God’s power the University flourishes — and we get blotto.”

Three days later the floor of the living room was littered with dozens of empty cartons of eggnog mix, an empty aluminum ten-gallon milk can which someone had gotten from a local diary and fifty empty bottles of booze ranging from Rye, Scotch and Bourbon to Vodka, Gin, Curacao and Crème de Menthe. All had been mixed with the milk.

During the binge, to which dozens of revelers had come from all over the campus contributing alcoholic gifts, we decided that with eggnog you just had to have a cozy fire. So after going through the meager wood stash, we’d chopped up most of our furniture with the dormitory fire axe and burned it. We spared the bunks and a couple of overstuffed chairs. After that we fed the fire the wooden parts of our player piano that had broken down after hours of playing Dixieland. Then we consigned to the flames, clothing that bored us (including duds owned by the one roommate who was home and who barely spoke to me again in his life).

I was the life of the bash, telling jokes, performing nutty pratfalls and trying to out drink everyone. I woke up on January 15, 1951, on my twentieth birthday knowing I had hit bottom. I was an alkie. I was destitute. The only money I got was seventy bucks a month my father sent me — when he remembered. He seemed to detest me. My mother adored me, but was slightly ga-ga from her own alcohol problems and had little money to give me.

In the days left before the exams I fed myself orange juice filled with the fillings of Benzedrine inhalers and studied for some thirty-six hours straight. I just passed, but I was placed on a special dean’s list, the one for students about to be expelled. Desperate, I asked friends what the guaranteed easy courses were for the second term, the “guts.”

“Art history,” a roommate advised. “They turn the lights out to show slides and you can nurse your hangover with a beer. Art history is the classic ’gut’.”

I registered for Medieval Art and when my roommate heard that he exclaimed, “That’s the hardest course in the Humanities! If you pass that we’ll call you ’The Artful Tommy.’”

In the first lecture the professor, Dr. Kurt Weitzman, who spoke with a thick German accent, punched up a slide and said something like, ‘This is the pagan hero Orpheus as Christ. Christian artists, having no models to draw upon, adapted pagan subject matter, hence this complex iconography.’

I had no idea what he was talking about and was profoundly depressed that this course looked like the end of my university career. But I couldn’t keep the image of the young, radiant Jesus Christ-Orpheus out of my mind. Today, I can still see it as if the slide were up on the screen. That slide and that professor changed my life.

* * *

In 1961 I was a fledgling curator in the medieval department and The Cloisters of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. One night at dinner my predecessor told me about a work of art I should pursue. It was a cross carved intricately in walrus ivory – English of the 12th century – the rarest of the rare. I was intrigued until he laughed and confessed that he’d been joking; the cross was the best – or worst – forgery he’d ever seen. The faker was so stupid that on the placard over the head of Christ he had inscribed the words, “King of the Confessors” instead of the biblical, “King of the Jews.” This was the only cross with such a stupid mistake.

In the middle of that night I had one of those flashes. I woke up and muttered to my wife, “It can’t be a fake; no forger would dare invent something like ‘King of the Confessors’.”

Two years later I proved that the work was no phony and persuaded the museum’s skeptical director and the board of trustees to fork over the highest amount ever paid for any medieval work of art. In time I dug up ample evidence that suggests strongly that the magnificent cross is the one mentioned in the annals of the monastery of Bury St. Edmunds in East Anglia as having been “incomparably carved” in 1156 by one of the greatest artists in history, Master Hugo, as an anti-Jewish piece of propaganda. Today, even those scholars who dismiss my theory that it is religious propaganda agree that this work is the most spectacular survivor from English medieval times.

* * *

And talk about outrageous. I was surprised to learn not long after taking my oath of office in 1967 that the police in New York City’s Parks Department are not governed by the Police Commissioner but by me, the Parks Commissioner, I visited the Central Park precinct housed in a crumbling neo-Gothic structure on the transverse drive at 85th Street to introduce myself to my troops and to buck them up – their morale was pathetic. When I asked why, an officer in the back row raised his hand and said something like, “I’ll get disciplined for this, but you gotta know. Our morale is lousy because of the murders in the park. But, believe me, Commissioner, these dead guys are killed elsewhere and dumped over the walls surrounding the park.”

I quipped, “If you can prove it to me, what’s wrong with picking up these bodies, put ‘em in our squad cars and dump ‘em in someone else’s precinct?” The squad room erupted in cheers.

Six months later the New York Daily News had a story, “Crime Plummets in Central Park” and I was quoted, “From now on folks will have to move in to Central Park – even at night – to be safe.”

* * *

One sentence triggered the eventual blockbuster art show. It happened in my office sometime in 1971 during a routine staff meeting when I was complaining bitterly that the Metropolitan could never mount great loan shows from abroad because insurance companies were refusing to cover them. I grumbled that I wished we could have in America the same thing as existed in Great Britain, a Parliamentary indemnity. But it would be impossible because American art museums were private whereas in England they were government owned.

A new hire, Daniel Herrick, the vice-director for Financial Affairs, spoke up. “Mr. Director, there is one loophole to that privately owned deal – the Federal government does indemnify some corporations with overseas outlets against natural catastrophes.”

“That’s it,” I said. “We can create an arts indemnity from that!”

Within a week Herrick and I were in the office of the under-Secretary of the Treasury, who, when we told him about the loophole, smiled and said in a broad Texas accent, “I was hoping you boys hadn’t found out about that.”

In due time President Gerald Ford signed a bill that entitles the State Department to indemnify art shows coming from abroad – now up to half a billion dollars a year.

* * *

After I left the Metropolitan I became the editor-in-chief of Connoisseur magazine. In 1986 I was preparing an article comparing the acquisitions of the jewel-like Kimbell Museum in Fort Worth with those of the staggeringly rich Getty Museum. An associate curator in the Getty’s Greek and Roman department took me to the museum’s conservation studio to show me a secret new acquisition, a marble Greek archaic kouros of the 6th century BC.

As soon as I saw it, I knew it was bogus. I grabbed the curator’s arm and said, “Have you paid for that thing?”

“Is this a joke?”

“It’s a fake. The color – like café au lait – is not ancient; the proportions are off for that early date and the damage is suspiciously light. And his prick is too big.”

“What do you know?”

“I used to dig at an ancient Greek site in Sicily and 6th century BC things do not look like that.”

Two years later the Getty finally agreed with my flash of intuition and changed the label on their $9 million kouros to read that it was “either 6th century BC or 20th century.” I was ecstatic.

* * *

The Metropolitan Museum got into a scrape with the Italian government over the gorgeous calyx krater painted by the genius Euphronios around 510 BC depicting the hero Sarpedon being wafted off to heaven by Sleep and Death. Back in 1971 I had purchased the stunning work for the Met for the world-record price of $1 million. The Italians vigorously sought its return, claiming that it had evidence proving the vase had been illegally excavated from an Etruscan tomb in Cervetri and smuggled out of the country. But until 1986, when I found new evidence, I believed it was a legitimate acquisition. That new information proved to my satisfaction that the Italians were right, as I wrote in my book on my ten years directing the Metropolitan, Making the Mummies Dance.

During the acerbic contretemps between the Met and the Italians that took place between 2005 and 2007, I was interviewed by an officer high in the ranks of the special Carabinieri division charged with looking after national artistic patrimony. I agreed to help them and went to the Italian Consulate in New York to draft an affidavit that would help the Italians get back the vase.

As I was leaving, worried about the hard line the Italians were taking, I said to the officer dealing with the case, “A little word of advice, Maresciallo. Don’t be too harsh on the Met. Don’t be too grabby. You’ll have to deal with the museum forever. Why don’t you share ownership of the vase? The Met owns several pieces with other governments – and one was like the Euphronios, I mean, smuggled. Did you know that the Met has an agreement with Mexico, now going on forty years, in which the Met agrees not to buy pre-Columbian works smuggled out of Mexico in exchange for a series of great loans? Mention this to the Minister of Culture.”

Maresciallo Angelo Ragusa said, “Ministers come and go, we decide this kind of arrangement. I had no idea these things existed. We shall think seriously about them.”

So, I wasn’t surprised when several months later the Metropolitan announced that the Euphronios vase would go back to Italy in exchange for a lifetime of loans “equal in beauty and importance” to the krater. I immediately emailed my successor at the Met and, without revealing my role, told him I thought he’d made a great, statesmanlike decision.

* * *

These anecdotes indicate that I am pretty much what that Johnson O’Connor guy said. I am talented, full of ideas, full of myself (and I think rightly), arrogant, intuitive and visually acute.

And as you will also find out, I am boastful, outspoken, blunt, honest, wild, slightly sinful, impatient, angry, disrespectful of danger and intolerant of hypocrisy. I am above all controversial. I am arguably the most controversial person in the history of American art museums. That’s because I brought about a lasting museum revolution worldwide by making the Metropolitan highly popular, making a business out of the place, getting rid of duplicate works of art and mounting dozens of blockbusters.

Lots of people don’t like me, saying that I destroyed the Metropolitan, that I’m a liar, a hack, an opportunist, that I inflate my numerous accomplishments and that I am essentially an egotistical asshole. But people who cherish facts and the truth, the ones who matter in this world, do like me or at least respect me.

Enough said, what follows are bits and pieces of my zigzag life. Once you’ve read it, you might become a fan.