If Eaglebrook School was my prime parent in my formative years, Martha’s Vineyard was my secondary one. My mother let my sister and me do pretty much what we wanted. The little structure there was entailed sailing races, but the rest of the time I hung out with my gang; Petie was with hers. You could always tell where the action was in Edgartown from the large number of bicycles stacked on the fence at our house.

In sailing I started off crewing for my sister in a lovely little centerboard boat. We lost every race so I dumped her and crewed for years for a friend in the same type of boat, which was the hottest in its class, and we never failed to gain the silver cup for the season’s first place.

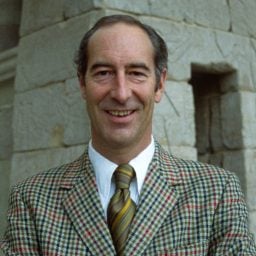

My best buddy and virtual twin was Alden Augustus Thorndyke Duncan III, known as “Slippery-Fingers Dyke” because of his card tricks (and his skill at shoplifting, in which I didn’t participate after the watch debacle). He was the son of my mother’s closest friend, and an heir to the Lea and Perrins Worcestershire sauce dynasty.

Another close friend was Grant McCargo, who was a year and a half older. Grant had his driver’s license and once the war was over was allowed to use the family car. Four or five of us would get liquored up and race around the island in the McCargo car, hitting every party, invited or not. For several summers three New York City brothers, the Goldmans, Chet, Doug and Bo, would show up and stay either on a beach or, clandestinely, in houses of friends. Bo, my contemporary, was my favorite because of his ability to mimic anyone. I must have been a bit jealous of him because when he was around, he outshone my attempts at wise-guy humor. He was a heavy-set, round-faced Pixie who could run like hell and pedal a bike faster than the rest of us. I’m convinced he had an I.Q. in the genius level. At Princeton Bo excelled in the Triangle Club for which he wrote the book and music for the smash hit of the graduating year. After Princeton he would write Broadway musicals and would be awarded two Academy awards for writing the movies One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest and Melvin and Howard. I adored him although he married one of my girlfriends, Mab Ashforth.

In Edgartown I fell for Grant McCargo’s sister Marian, who was blond, blue-eyed, athletic and ravishing. This adolescent affair was strained. We did go to dozens of movies, dance wrapped around each other at Yacht Club dances, hold hands walking the mile or so home, and even kissed — ineptly. I kept a list of kissing techniques that I saw in the movies, but never could figure out where to put my long nose. “My God, what if our teeth clack together,” I’d think and back off.

In my later teens in Edgartown I fell in love (and she with me) with a local girl (“Jesus, a townie,” Dyke muttered), Jean Galley of a venerable Vineyard dynasty. All of fourteen, she was a young woman of startling physical beauty, green eyes, coal-black hair and breasts the size of small doves. We sneaked into movies usually in Oak Bluffs so as not to be seen by my crowd or her parents or brothers, who knew how mouth-watering she was getting to be. Our trysts took place at the base of the Edgartown light down a long boardwalk, well hidden. We broke up reluctantly after two summers because she was admitted to Boston College at the age of seventeen. I have no idea what happened to the young woman after that.

I had a variety of jobs ranging from caddying double bags, which I loved since I got a dollar a hole, hoeing corn — the farmer was amazed how knowledgeable I was — and washing cars. One of the more lucrative odd jobs was lugging an Indian Pump on my back for extinguishing occasional brush fires. It was Dyke’s idea to prolong the work by starting a little fire here and there when the main one had been controlled. We stretched the work from two days to five.

I worked at a local raw bar and got so good at opening clams that I’d boast to the customers if they could slurp them down faster than I could open them, they could have a free dozen. I usually won. I was paid in clams and at the end of the day, I took home four or five dozen to the delight of my mother and her hangers-on.

For my gang the halcyon days were the war years. In 1944 the 3rd Army encamped on the flats at South Beach near Katama to practice amphibian landings. We became junior black marketers, selling the G.I. s honey and marmalade, beer and our parents’ liquor (most of the time slightly watered down). In exchange we got web belts, scabbards and helmet liners. Appropriately suited up, we played war games for hours.

On Chappaquiddick, near the Cape Pogue lighthouse, was a Navy bombing and rocket range with a huge painted wooden target. Grant, Dyke and I would lie in the center of the thing watching the dive-bombers make their runs. We felt perfectly safe because despite thousands of bombing runs, the target itself had never been hit. When the pilots spotted us they made low passes, wobbling their wings trying to get us to move, only to be greeted by happy waves from us. We made collections of rocket and bomb fragments.

We did lots of other crazy things. An older friend owned a twenty-foot catboat. He suggested that Dyke and I join him on a cruise over three or four days through the nearby Elizabeth islands. The boat had four bunks, Sterno for a stove but no toilet — we either jumped overboard or used a bucket. For provisions I bought three cartons of Chesterfields, six-packs of cheap local ale and loads of junk food. My mother was on the mainland visiting friends and our skipper forgot to tell his mother about our cruise.

We stayed out five days having a glorious time. Seeing thunderous black clouds to the west one day we holed up for a day and a night of smashing rain as a savage front ripped through. When I returned to Edgartown, I sashayed into the house. My mother screamed when she saw me, impetuously smacked me over the head with a lamp and then gathered me into her arms crying about her baby being safe. I suddenly got it. Our infuriated parents who had all but resigned themselves to our deaths then took us to the Yacht Club. Attending our “inquest” were four Coast Guard officers who, they claimed, had been searching for us.

They read us the riot act. In the middle of the inquest and the chewing-out, I saw that my skipper was about to explode. I was too and impetuously talked back. I apologized for the breakdown in communications to our mothers but then explained that we’d done nothing wrong in sailing out alone and without a radio. Our seamanship was excellent; we had gone out and come back without incident and had had the good sense to hole up during one of the most vicious storms of the summer. I suggested that the Coast Guard had been derelict in not finding us — it wasn’t that we were hiding. I ended my speech by saying the Coast Guard ought to apologize to our mothers for not having located us. To my surprise and delight, they promptly did. It was a grand moment for me, a sort of maturating moment.

My drinking and carousing somehow got to my father (I suspect my mother had tipped him off) and, alarmed at the many times I — or had it been my twin, Dyke? — had been spotted lurching around town, he yanked me out of the Vineyard and restricted me to his new summer digs. I was fifteen years old.

Pauline had bought a Victorian house in Stockbridge, Massachusetts, on “Nob Hill” — to me, obviously, “Snob Hill.” The house had a gracious porch overlooking a two-acre impeccably mowed lawn with five stately maple trees. She left Long Island because “Walter was being given the eye by every woman unattached or very much attached.” I was amused at the idea that my straight-laced and by now Christian fundamentalist father might have had an affair.

My first friend in Stockbridge was the French live-in gardener who had a two-bedroom apartment over the garage in the back of the property. I spent many hours chatting with him — my governess Mimi Precourt had taught me enough French to get by — and eyeballing his sexy French magazines.

My punishment was to work all day raking the white-pebble drive — one single stone out of order and Pauline had a tantrum — or polishing the brass fittings throughout the house, fire-dogs and door pulls — one fingerprint smudge and Pauline had another fit.

Stockbridge was populated with New York and New England high society and I soon met the local aristocrats who cherished gambling, drinking, skinny-dipping, playing pool and billiards and staying up until long after midnight. Just my style.

The first Stockbridge “aristo” I encountered was the son of one of my father’s golf partners, Chauncey Loomis, a lithe champion wrestler, a year older than me, with a face like Jean-Paul Belmondo’s and a genuinely sophisticated manner.

Vital to my upbringing were summer residents Jim and Patsy Deely, who were at the epicenter of Stockbridge nightlife. They were in their mid-twenties and lived each summer on a grand estate named “Ingleside,” built by Patsy’s grandfather, the author of the hugely successful 1920s book Stover at Yale. Jim was a dedicated Catholic with a taste for high living and fine liquors. He introduced me to odorless Vodka and it became my exclusive summer drink. His knowledge of the fine arts was protean and he was wealthy enough to collect Courbet and Rodin. Patsy was a lovely, bold, funny woman with a laugh that could warm hearts two rooms away. She, too, was avid about the fine arts and never missed a museum exhibition. The Deelys spent part of every summer in Florence or Paris or London.

Other luminaries were Rudd Truax of the family that owned a major share of the New Yorker magazine and Celia de Gersdorff, a Boston beauty with a heart yearning for adventure. I had a crush on her. There was also a couple whose names I’ve forgotten who had a house with a pool table where I honed a serious game. And there was the happy-go-lucky Harrison Suarte who, in his mid-twenties, was on a full Army disability pension. As a lark when he was fifteen he had enlisted in the Army and was sent to Europe and thence to Bastogne where, in the real version of Saving Private Ryan, he was whisked out of the Battle of the Bulge to safety, bellowing with rage about having to leave what he thought was “a barrel of fun.”

On a typical Stockbridge evening I went to my room and, ostensibly, to bed at nine when Pauline and Walter retired to their quarters (where I was seldom allowed alone, Pauline never having forgotten the watch ring). After their toilet flushed, I’d creep down the narrow stairs from my third-floor room. Out the door I’d walk on the grass to where Chauncey Loomis would be waiting in his small car, engine off. We’d give a push, get in and coast down “Snob Hill” until we got far enough away for my parents not to hear our departure. There he’d throw the clutch into second, start the engine and we’d roar into a night of decadence.

We’d hit the Deelys for a few drinks and then go to play pool and billiards or gamble — we gambled frenetically. One night in 1947, I elected to play banker for a roulette game. I had no real idea what I was getting myself in for — all the cash I had was around two hundred bucks. The house — meaning me — won it all that evening. My take was a staggering $1,500 plus.

At Stockbridge after the gambling we’d drop in for last drinks at the Deelys pool house and plunge naked or sometimes fully dressed into the heart-stoppingly cold water to avoid the whirls, which I had every evening and hated but which never stopped my carousing.

Chauncey would drive me back to “Snob Hill” where I’d sneak back in to my bed around three or four in the morning. My father would awaken me at six. He became increasingly anxious because I was losing weight and was developing huge circles under my eyes. He sent for a doctor who, unannounced, waylaid me in my room. Since he had attended some of the late-night parties, he winked at me and told Pauline and Walter that I shouldn’t be awakened so early for a couple of weeks and perhaps my work load should be reduced.

My father suspended my penance and urged me to take up golf, saying, “It’s a good way to get ahead in business.” The Stockbridge course is one of the prettiest and most challenging in New England. The eighteen holes wander through the valley of the Housatonic River and eleven are water holes. I started an operation with a friend, diving, finding and presenting the barely marked balls to the pro, who paid us back by giving us lessons. My father, not knowing about this, thought I was something of a self-taught golf prodigy. My best of best was a carded 79, but normally I wandered from the low eighties to the mid-nineties. All I ever wanted to do was to whack the hell out of the ball and, for me, driving 200 yards and sometimes more was golf heaven. My short game was erratic and on the greens, I was too hurried. My father was straight and conservative and patient on the greens. His game drove me nuts.

I never had a girlfriend at Stockbridge. Pauline introduced me to “little Peanut” who was summering from Boston. She was diminutive and pert but not the type I could take with me on my night’s carousing. We mainly went to movies in Great Barrington or Pittsfield and hesitantly held hands.

I was given the family Packard to drive and on one of our evenings when I was cruising slowly along, a pick-up bumped our tail gently. I squeezed “Peanut’s” hand and snarled out of the side of my mouth, “Hang on, we’ll ditch these idiots.” That Packard really took off when I floored it. We got up to over eighty and, seeing the pick-up drop behind, I abruptly slowed and made a dangerous right turn and parked under some pines. The pick-up passed by.

“Peanut” literally clawed at me to bring my head down to her lips and kissed me hotly. We got to second base. Yet, the next time I called her; she wouldn’t speak to me and soon went back to Boston. I guessed that she might have told her mother of the exciting drive.

I made one lifelong older friend in Stockbridge, Brooke Marshall, who with her husband, Buddie, had a lovely home with a pea-green pool in nearby Tyringham. Brooke was an editor of House and Garden. Pauline was pursuing her for she wanted her house to be published in America’s finest shelter magazine. Brooke took a shine to me despite my rebellious nature (she knew of my nonstop nightlife), took pity on me and said I could come to her house anytime I wanted to drop by. I did a couple of times a week. She listened to my parental woes and gave me some helpful advice on how to handle an egotistical woman like Pauline and how to deflect my father. I adored her.

In 1953 Buddie Marshall died and shortly afterwards Pauline went to Tyringham to console Brooke. Walking up to the house she heard loud tango music. Pauline sneaked to the window and peered through the Venetian blind. There was Brooke dancing with herself madly to Tango music, crying out “Vincent, Vincent, Vincent!” She married the wealthy Vincent Astor a few months later and started her legendary career as Queen of New York’s social world and of philanthropy. The inimitable Brooke Astor died in the summer of 2007 at 105 years of age.

At the end of that summer of 1947, I took my $1,500 gambling stash and joined my wild friend Dyke Duncan in Edgartown for one last fling. We rented a bedroom over some garage, rented a car and for a week maintained a buzz every minute of the day or night. At night we drove our rented convertible backwards to keep the odometer down, since we were paying by the mile. Our Vineyard vacation ended after a party we threw on South Beach. The bash ended just before dawn when we tipped over and set on fire a sand-moving machine. Knowing we were cooked, we had a quick swim to sober up, raced to the apartment to get our stuff, drove directly to Oak Bluffs where we turned in the car, ran onto the first ferry out of there and disappeared. The sheriffs tried to find us for a day or two.

Dyke and I also hung out in New York City during school vacations. Starting when we were fifteen, we would haunt as many debutante parties as my sister could get us invited to. For those we had no invitations to, “Slippery Fingers” dreamed up a novel way to crash. We’d go to the desk where the tickets were being examined and would walk in backwards, very slowly, chatting away animatedly waving a champagne flute. “They’ll think we’re walking out,” Dyke explained confidently. It worked!

I almost croaked after one party. It was during Christmas vacation in 1947 at the Saint Regis Hotel. Around two in the morning, well oiled and feeling oncoming whirls, I decided to get a cab home. But there were no doorman and no cabs — the streets were covered by a foot of snow. It was the great snowstorm of ’47, the one that dumped something like three feet in twenty-four hours. I started walking home in my thin Chesterfield overcoat and the fancy new patent-leather dancing pumps I’d bought for the party. A few people on cross country skies or snowshoes were making a winter wonderland out of Park Avenue. I remember a top-down jeep roaring up and down the avenue, smacking through two-foot drifts with the inebriated passengers shouting joyfully. They ignored my hitchhiker’s thumb.

The hotel was on 56th and Fifth Avenue, my home was on First Avenue and 72nd Street. The new shoes began to fall apart three-quarters of the way there, revealing not leather in the soles but cardboard. So much for Brooks Brothers. I walked the last two long crosstown blocks in my stocking feet and at least sobered up. My mother thawed out my feet, laughing that the liquor had saved my life.

I wanted to go to Brown University because Dyke and Grant were going. I was a shoo-in legacy and my father was a life trustee. When I told him, he retorted, “Those two bad influences will get you fired from Brown. You can go to any college or university in the nation, but I’ll pay your tuition and a monthly allowance to only one, Princeton.”

“Where’s that?” I asked, not entirely seriously.

I was accepted promptly. Architecturally, I thought the place looked Gothic Gloom but the life didn’t look all that bad; Chauncey Loomis was there and Bo Goldman was going, as was Tom Godolphin, the Dean’s son, whom I had met through Bo. Amusingly, my father’s prediction was correct, both Grant and Dyke were expelled from Brown.

At the Hotchkiss graduation my father informed me that I was too old to waste my summers beaching at Martha’s Vineyard or golfing at Stockbridge and from then on I would have to go to work. For the summer of 1949 he had lined me up a job as a copy boy at the New York Mirror, a Hearst tabloid at 50th Street between Third and Second Avenues. I would be paid fifty dollars a week and would have to work every other weekend.

I was thrilled to be on my own in New York City. My mother was in Edgartown and my father was in Stockbridge every weekend. Dyke opted not to sully his hands with common labor and joined the gang on the Vineyard. I commuted every day to the Mirror on the Third Avenue trolley.

The paper was housed in a building on the brink of condemnation. The presses were on street level and dozens of Mirror delivery trucks zoomed in and out of the broad delivery dock day and night. The newsroom, the linotype machines and the Teletype room were on the fourth floor.

Copy boys — four of us per six-hour shift — sat on two wooden high-backed benches between batteries of rewrite men and the copy editors who perched inside an elevated round pit. The head copy editor was Jack Lait, an obese man of unhealthy complexion and wispy white hair who wore both a pair of wide suspenders and a thick belt. Soon I was wearing both.

I’d spend the first hour folding two pieces of paper with a carbon in between them into the shape of a half-arrow which the re-write men could thrust into their typewriters quickly so vital news and gossip could get to the waiting public in a flash.

Reporters phoned in their stories to re-write men. When a re-write man had finished pounding out his story — always with two fingers — he’d call out, “Boy!” One of us would race to pick it up and hand it to a copy editor. An editor would shout, “Boy!” and one of us would pick up the edited copy and dash to the linotype room to a man sitting at an organ-sized machine that made the lead type from a pool of molten lead bubbling away in a cauldron hanging at one side.

From time to time bells would jangle in the Teletype room to signal a story of massive significance was coming over the news wires. We would race to rip the paper clacking out of the machines and rush it to an editor who’d see if it were worthy of the Mirror.

Most of the time the bells meant the results of some horse race. I learned in my first week that the Mirror was more a betting parlor than a newspaper. The bettors were citizens in the know who wandered in off the street. All bets were placed with a linotype operator, the results would ring through the Teletype and the bettor would go back to the linotype room or not depending how the nag fared.

I idolized the re-write guys and especially Ernie Savelson, a fire-plug of a guy with a day’s growth of beard and one cig in his mouth and a second behind his ear. When he wasn’t typing he seemed to be reading a detective novel — he had a stash in his desk. One morning before he arrived, I happened to open a drawer. There were detective books, all right, but there were also Dostoyevsky, Becket and Burroughs. I kept his secret.

Savelson worked for a week on one sensational story that pushed circulation upwards a few ticks. A twenty-year-old guy was driving his pickup in Rhode Island and gave a lift to two young women in their early twenties. The girls were, as Ernie described them, comely and nicely stacked. One was a brunette with green eyes and the other a blonde with blue eyes. A couple of miles down the road the two ladies enticed the young man into a motel where they held him for several days and “against his will,” forcing him to have repeated sex.

Ernie tapped away every day, finding out more details for every edition. The girls were never named, for the young man neglected to press charges. Today I have the suspicion the whole thing was made up.

Another idol of mine was a handsome re-write man who wore a hat at all times with a press ticket stuffed into the band. One day just before noon, the doors of the newsroom slammed open and a tall redhead of jaw-dropping beauty stepped in, spotted him typing away, came over to his side and began begging him, “Take me back, please, Bobby darling!”

The word flashed around the floor and a crowd quickly assembled.

He ignored her even when she started to cry, “I’ll love you even more, Baby. I’ll do anything for you; only take me back.” Then very gently, he got up, sighed impatiently, walked her out the door, slammed it and muttered, “Well, enough of that!”

Weeks later, having noontime chow with him at P. J. Clarke’s, which back then was just a local bar, he laughingly told me that she was an actress friend. They’d rigged the scene in the hopes that he would get a promotion at the Mirror. He shortly became one of the gossip column re-write guys.

I got to know nationally syndicated gossip columnist Lee Mortimer who wrote with Jack Lait a series of books entitled New York Confidential or Los Angeles Confidential, brimming with racy tales — most created from scratch — of the rich and famous. Every few weeks Lee would stumble into his newsroom office with a mouse or a split lip and tell me how he’d been assaulted by Errol Flynn or some other star at El Morocco or some other glittering waterhole and had held his own.

The editor-in-chief liked me, perhaps because I got his coffee real fast, and promoted me to the distinguished post of letter writer. The Mirror seldom, if ever, received readers’ letters except to threaten suit over a horse picked to win in one of the daily picks columns that didn’t. There were three of us who created the daily letters. Editorials would often follow up on the letters. There were two kinds of letters, the editor explained to me — table-thumpers and weepers. I became skilled as a table-thumper and once generated a lead editorial by grouching about the plethora of potholes throughout the city generated by a heat wave. The Mayor replied to my fake missive. I loved it.

Every weekend that my father wanted me to drive up with him to Stockbridge I told him that I couldn’t because I had to work. I made it through the summer with only two Stockbridge weekends. The Mirror had a seldom-used box behind home plate at the Yankee, Giants and Dodgers stadiums. I’d go usually with a re-write man and keep score. I saw some memorable games. I was there when Bobby Feller no-hit the Yankees. I was there the afternoon Charlie “King Kong” Keller hit four home runs in a game. When the Cardinals were in town I’d go to Giants stadium or Ebbets Field and watch my favorite player, Stan “The Man” Musial, hit five for five. Years later I met “The Man” and have a baseball dedicated to me and signed. I still treasure it.

In the evenings I’d either stay home and cook up some canned spaghetti and get blasted on straight-up martinis or go to a Third Avenue bar — which then had separate entrances and rooms for women — and nurse some beers.

In my last weeks at the Mirror, I was promoted to what was laughingly referred to as the “culture department.” My duties were to assemble all the lines — still in lead galleys — written by columnist Drew Pearson and winnow them down so they could fit into a column of a certain length. Not that I actually edited Pearson, but he always wrote more each day than we could use. I would read the lead type — the letters were upside down and backwards so it took a bit of time to learn the trick — and select the number of lines I needed, placing the rest in other trays to be used in a day or two or even a week or perhaps never. Sometimes the column ended a bit oddly because of my arbitrary cutting of lines, but no one complained.

I ended my summer tenure by working for a swell guy named Sidney Fields, who wrote “Only Human,” a popular and well-written human-interest column. Fields sought out such offbeat characters as the sole blacksmith in the city or the woman who worked on the express train subway tracks and who was a serious painter after hours.

I got a lot from the Mirror. I learned how the news is really dished up and developed an affectionate cynicism about it. I learned to love lean, clipped sports-writer’s prose. I started to write again, mostly short stories about life in the city, which were never published.

In my freshman year at Princeton I drank a lot, played incessant cutthroat poker wearing a green eyeshade. I would dribble through my seventy bucks a month allowance fairly quickly. A freshman was not encouraged to get a part-time job lest the distraction impair the rigors of the first year of truly serious advanced education.

The curriculum was studded with a series of what Princeton termed “electives,” required courses in history, mathematics, physics and psychology. I chose psychology since I’d had such experience with a psychiatrist. Psychology 101 turned out to be a “gut.” English was a breeze since I had already gone through the book list at Hotchkiss. I had a deceptively easy time in freshman year.

I would take the train in to Penn Station at least twice a week and hit my favorite nightclubs. I’d end each night at the Orpheum Dance Palace at Broadway and 47th Street, which was a place of assignation. When the Orpheum closed at 4:00 a.m., an attractive blond with heavy lidded eyes and a slurred voice took me back to her joint and I screwed for the first time. I wasn’t nervous in the least and experienced the joys of the hearty 69.

Partly because of my ruined right knee and because I was into drinking I didn’t sign up for any athletics at Princeton. I thought I was too sophisticated for “kids” games. What a mistake, because I once scrimmaged with the varsity lacrosse team and the captain and coach, seeing what I could do in the goal, wanted me to try out for junior varsity. But I made some dumb crack about needing time for the Right Wing Club, an organization devoted to drinking, which I thought was very chic.

My marks at the end of the second term made me believe that Princeton was a breeze. I signed up for the last electives I’d have to take confident that I would do well. I felt a bit guilty that I’d stopped creative writing and had tossed aside my Hotchkiss obsession to read. But I had a great gang of friends and the constant boozing kind of cut into the old obsession.

The summer job after freshman year was at John David, a men’s store chain in Manhattan which my father had bought. The store I worked in at Fifth Avenue and the downtown corner of 49th Street was the flagship emporium. The merchandise ranged from the top maker of men’s suits, Hickey Freeman, on down. A three-piece Hickey number sold for $250 — something like $2,000 these days. You could come into John David in a sweat suit and several hours later emerge as a fashion plate.

My father had bought the chain from Colonel Ladue who stayed on as general manager. Every morning, at random, the stiff-backed, dour Colonel passed through the store without a nod, a smile, or a crinkle of the eye. I made sure I greeted him like a God.

First I wrapped packages and then was promoted to floorwalker or “Service Executive.” I was given a Haspel sharkskin, 39 long, double-breasted number with a white flower in my lapel. I was positioned at the main entrance with a broad smile pasted on my face. I learned to puck up men’s sizes within a couple of days because the salesmen always referred to people by their suit sizes.

Someone would enter the store and I was on him at once, smiling and asking, “May I help you, Sir?”

If the potential customer mentioned the name of a salesman, I would call out “Mr. Gard, See You.” Or, “Mr. Mintz, See You.” Or, whatever the name was.

Otherwise I called the next salesman in rotation.

By the end of the first week, two of the sales staff — not the venerable Gard or Mintz — had offered me a quiet share of their sales percentage if I’d give them a “See You,” even if the customer, especially someone from Latin America, hadn’t mentioned their name. Every salesman dreamed of the day that that legendarily wealthy Brazilian would come in and buy twenty Hickey Freemans.

The word got to archrivals Gard and Mintz that I had been approached to rig the “See Yous” and had spurned the request. Each separately took me aside and thanked me for not caving in. Gard said, “Only schnookers ask to be brought out of normal rotation. That rich Brazilian will come to everyone in his lifetime.”

A rich Argentinean did come in that summer and did order and pay for loads of Hickeys and the young salesman who had just started work made a hefty percentage.

In time I was able to spot the hookers in a flash — the women went to the suit racks looking for prey. The male homosexuals haunted the shoe department.

I excelled in spotting “Coolers,” the guys who came in to get away from the blinding heat of a New York City August. They would invariably fiddle at the tie rack and then saunter over to the suits and linger near the 42 regulars. I was merciless with them. I’d walk right over and give them the “service executive” smile and the “May I help you, Sir?”

“Just looking.”

“Well, Sir, you don’t belong in this section; you’re a 40 extra-short-portly.”

I’d lead them directly to the Hickey Freeman racks and when they saw the prices on the sleeve tickets they’d flee.

Although I had a good time at John David and earned one hundred and eighty dollars a week and saved money by eating the exact same meal at a local Automat for two bucks, I began to get cramps and severe back pains from standing on my feet all day. The pain convinced me never to go into retailing.

Previous Chapter – Next Chapter