Having lost our major client, Hoving Associates began to retrench. I cut back severely on my expenses and resigned from the Century Association — I had lunch there once a year and that with the annual dues cost something like $1,800. On my last lunch at the place, I sat at the common table with John Lindsay, who was recovering from a stroke and could barely speak. Yet, he hadn’t lost his wry sense of humor.

“Tom, I was hit by the stroke right here at lunch. I was going to take a cab home, but some idiot called 911 and when I got downstairs the place was full of the reporters, TV crews, police and emergency medical guys. They threw an oxygen tent over me and I was lying on the floor with crowds of reporters and TV crews surging around. I spotted Raymond, our doorkeeper for decades here; you know, the guy who was vehemently opposed to women coming into the club. I got this tickle in my brain and motioned him over. I said, ‘Ray, see what happens when they let women in here?’”

I was able to thank him for his quip about “making the mummies dance” for the title of my memoirs.

He laughed and said, “You should have stayed in politics.”

“Well, John, an outspoken guy like me who seeks trouble might not be so electable.”

“The way things are going I guess you’re right. Sad. You’d be better than George H.W. Bush. He’s one of the more irresponsible guys I ever met — the only one of four U.N. ambassadors who never met with me to discuss the on-going problems of city-diplomatic relations.”

As I flailed away looking for clients, any clients, Nancy wisely invested the Mummies advance and the Hearst settlement money. I made some money from speeches and articles. At times not enough to achieve proper cash flow even to pay our marvelous assistant Marianne Lyden. I got loads of offers ranging from a PBS series on world travel, another on celebrated artists like Taj Mahal, Tony Bennett, a fine painter as it turned out, and Anthony Quinn, a so-so sculptor (who, amusingly, used the same Italian stonecutters who had ginned up the Getty kouros to make his marbles from his plaster models, or so I was told). But they both crashed. The same thing happened to a show that my old 20/20 producer Av Westin was putting together for a Time Warner cable company in which I was to moderate a group of four Time, Inc. pop culture specialists. The pilot didn’t impress.

I did some consulting work for several computer companies. Classical music came back into my life because of computers and I developed an MP3 player of sorts. Over the years I have collected thousands of hours of music on a variety of players. Today I cannot think of being a few minutes without access to classical music or even the latest pop or hip-hop tunes.

A number of travel gigs came up that were especially entertaining. We wrote up our fine old skiing hotel in Zuers, the Loruenser, for a travel magazine. I was called upon to give a pep talk to the salespeople for Remy Martin at their Las Vegas convention. The magazine Bon Appetit asked me to come to Egypt, to a lavish tent erected near the stepped pyramid of Saqqara for a speech on its mysteries.

We signed up for three cruises and a biking trip through the Dordogne — lectures with pay and all expenses paid.

There is nothing like the Dordogne for cuisine, wine, spectacular views and Romanesque art. We ate like trenchermen and drank ourselves into delightful stupors and then early in the morning mounted up and biked, sometimes at flank speed for five or six hours, often up decisive hills to collapse in fine inns and relais. My lectures were about the glory of the Romanesque style and I waxed poetic at Conques and the cloister of the divine Moissac.

I’d much rather bicycle than participate on a cruise, but the money was with the cruise ships. I gave lectures on three spiffy cruise vessels and made some money — naturally all expenses were on the cruise lines.

One cruise was with a segment of the round-the-world cruise from Mombasa through the Suez Canal. On the flight to Mombasa the plane lost an engine and had to land in Cairo where we stayed two nights and as soon we were ensconced in our luxury hotel we promptly took a cab to the Cairo Museum and entered through the staff door. I calmly sashayed into the director’s office and welcomed the curators sitting as usual at the director’s table drinking tea — the same group I’d worked with years before on King Tut. When Nancy and I entered, there was a shocked silence and then one of the group observed with typical Egyptian humor, “Now that Dr. Hoving is here, we can get to the arguments and demands.”

I have been besieged to tell collectors if they have a forgery and have acted as a dedicated fakebuster many times, of course without any compensation, for taking money for an expertise would invalidate the act. I was shown a watercolor by the young Gilbert Stuart of a youthful George Washington which was being pored over by scientists at Yale University. In a flash — I didn’t need science for it — I told the interviewer (for this was for a TV bit) that the faker had made two mistakes. One, all the damage was far away from the face or the “money” part of the drawing. Two, he had utterly misunderstood the costume. Sometime later the scientists confirmed my initial impression.

I was also interviewed for a “feature documentary” on a so-called Jackson Pollock painting that a retired woman truck driver, Terri Horton, had found for five dollars or so in a thrift shop in California. The film, called Who the &%^$*&& is Jackson Pollock?, had me studying the large painting in the warehouse (the old Gramercy Warehouse where I had slaved for so long for Bill Pahlmann) and condemning it. It was far too neat and too sweet to be a work by the turbulent painter. One of the reasons why it was supposed to be a signature Pollock was a partial fingerprint on the back in blue paint. A forensic scientist, hired by Ms. Horton had found a similar partial print on a paint can in Pollock’s Long Island studio. The producer of the film told me that had to be the most powerful evidence that the picture was genuine. Very quickly I asked him, “Was Pollock ever fingerprinted?” Well, no. It was also established that the painting was in acrylic, a medium never used by Pollock in his lifetime. As we say in the distinguished art world, “Goodbye Charlie.” I don’t think the work is a forgery but more likely what I would call a decorator’s Pollock. Someone wanted an abstract expressionist canvas for a new interior and insisted on having colors in the “Pollock” that would go with the new drapes. It happened a lot.

I did many TV gigs, interviews and observation on the arts but my favorite moment was when I was the most despicable. The CNN interviewer Larry King asked me to appear with a right-wing Republican congressman named Dick Armey who opposed government funding of the arts. I was intrigued principally because my cousin John had just suffered through some agonizing weeks trying to manage the crises overwhelming the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C., where some sexually explicit photographs by Robert Mapplethorpe were to be exhibited. The show was canceled before it opened. Right-wing Senator Jesse Helms was furious with the cancellation. The senator wanted to be on national television collapsing in horror at the salacious photos. The imbroglio caused the Corcoran director to resign and the institution has really never recovered from the shock waves. (I would simply have put the offending material in a special gallery marked “Material May Be Offensive. For Consenting Adults Only”).

My performance was contemptuous, snide, interruptive, vile, rude — and great. My two best moments were when I described two paintings and asked if he would have given funding for them. One was a life-sized depiction of Christ crucified portrayed as having syphilis. “No funding!” the congressman retorted. That, I revealed, was the early 16th century Isenheim altar by Matthias Grunewald, one of the masterworks of all of art. The other was, I said, a huge scene with dozens of naked men and women, their genitals flapping in the fury of a cosmic wind, writhing, howling, and gesticulating. “No funding,” Armey bellowed. Well, that is Michelangelo’s Last Judgment in the Sistine chapel I told him.

I accused the congressman of deceiving the viewers in not pointing out that the NEA cannot give direct grants to living artists, only to institutions who do fund some of them. He looked genuinely surprised. I also accused him of using the issue as a re-election device. During off-camera moments he spat that I was a “leftist-liberal,” a charge that made me laugh and which I told the audience what he had said when the camera came back on.

King seemed confused; he perspired heavily and introduced me as the New York Times art critic. Armey said at one point that held never received such flack and abuse on any issue but this. You deserve it, I said. I told him and the audience that the banning of funding for certain artists had been what the Nazis did, what Stalin loved, what all totalitarian regimes had done through history. Armey said he resented that, and I answered “too bad.” When I said, motioning towards the congressman, that “this Bozo was curtailing the freedom implicit in America,” King told me not to call the distinguished congressman a “Bozo.” “Why not?” I shot back; anyone who would try to censor anything in a free country was a clown.

In 1993 I was asked to assemble for a consortium of Japanese museums a retrospective of Andrew Wyeth’s works funded by the newspaper Inichi Shimbun. The Wyeths were delighted, for many works purchased over the years by Japanese collectors would be seen for the first time in decades. They promised to send some of their finest pieces. My Japanese colleagues were geniuses at rooting out paintings and then persuading their owners to put them on view.

For the catalogue, I interviewed Andy, as I had done so many years before with his show I had put on at the Met, and he entitled the catalogue Autobiography. Houghton-Mifflin picked it up as a book and we split the advance and royalties. The Japanese catalogue was sensational with superior color and had a complete English translation of the text. On the cover — one of Wyeth’s only vertical works and thus perfect for the dimensions of the catalogue — was Distant Thunder, the one showing Betsy sleeping under a hat in the tall grasses of their Maine estate with her dog pricking up his ears at the sounds of a coming storm. Bill Gates saw the cover and soon bought the marvelous work for something like nine million dollars. The owner told me that Gates asked, “What’s Hoving getting out of this?” Come on!

Seeing the high quality of the show, I was able to convince the Japanese paper to pay for some of the expenses for one stop in America. Nancy and I arbitrarily decided on some museum in the mid-west where Wyeth hadn’t been over-exposed. Kansas City was our first try. Director Marc Wilson rejected it — perhaps because he was a close friend of John Walsh’s and had looked askance at my Connoisseur exposes and the all-too-revelatory Making the Mummies Dance. But Wilson finally accepted it and the show was a smash.

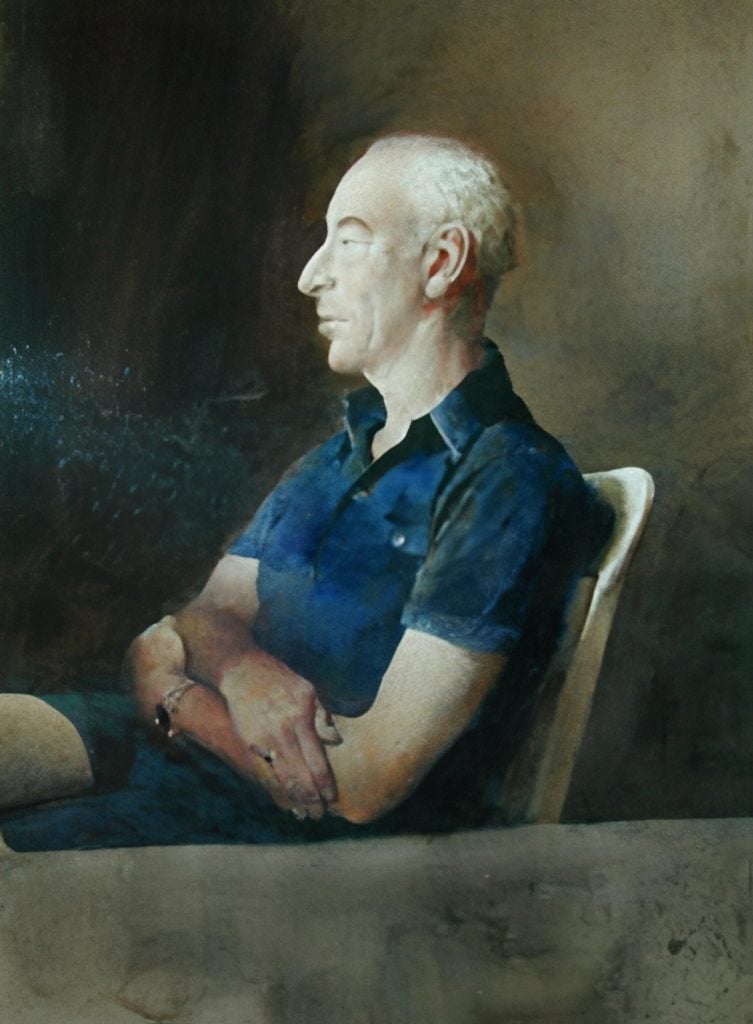

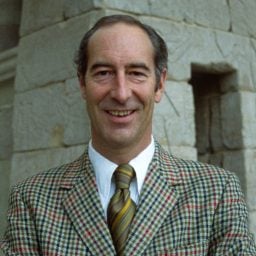

After this effort Wyeth asked me to sit for a portrait of me he wanted to call The Director. The sittings lasted for four days over two weekends in June during a vicious heat wave down in Pennsylvania. I sat in his father’s old studio in Chadds Ford dressed in shorts and a short-sleeved shirt. He sat on a low stool and shed his entire clothing over the hours because of the heat. “I thought the model, not the painter, should be getting naked,” I joked.

He answered, “You’re a guy, so keep your clothes on. Your face has always reminded me of some Medici Prince.” “And I want to execute a profile portrait like that Italian who did the profile medal and lion drawings and the strange animals — you know him, Pisanello.”

He began in pencil for this dry-brush watercolor and when he’d gotten the feel and the proportions — all of which he measured from my nostrils — he got his paint box out. All the tubes were mashed and scattered around like a bulldozer had crumpled them. He poured water from some vial into a pair of enameled tin cups and started to wash and scratch and tip the in all sorts of angles as he worked for three hours until the light started to fade.

He wanted me to talk every minute — “for animation” — and I spun through sections of my life, and, being a military nut my Marine Corps stories thrilled him.

After the first weekend I begged him to show me the results. He did reluctantly and to my astonishment I saw in the incomplete image, not me, but my father! He had never met or seen my father in the flesh or in photograph. He had simply captured the family bone-structure.

I saw the portrait again halfway through the second weekend of posing. I beheld a vision of a strong presence, not a likeness, but someone to be reckoned with. It was astounding every time he put the picture into the studio frame he had to see how the colors and the hues worked. It’s a portrait of a type I have never seen him do before — not a formal portrait but a piece of energy — ugly in a sense, dominating and ready to explode. I had a distinct difficulty telling him what I saw in it because that would have been as if I were, somehow, boasting. It was powerful and disturbing.

The last day it was hot as hell. I was perspiring like mad and had continually to blink my eyes for sweat was streaming into my eyes. I got a leg cramp and the pain continued throughout the entire three-hour afternoon session. Andy said he was about to crack and was getting woozy in the brain and eyes. I asked him if it’d be okay to try to set up my small video camera and shoot the final dickerings he was planning.

I placed the camera on a nearby garbage can and sighted through, started the tape and regained my seat of pain. It turned out by chance that if a professional filmmaker from 20/20 had set up the shot it could not have been better. It is the only time in his life that Andy has ever been filmed or recorded while working. I have recorded it on a hard diskette and have taped it to the back of the portrait.

Then Wyeth abruptly said, “Just about now, I can wreck it, maybe I should just finish.”

“Yes,” I cried.

“Here, it’s yours. I give you the reproduction rights, too. Sell it if you want. Crop it. Just use the head for resumes and the like. That white hook of the chair is a symbol of your inherent cruelty. That gray shape in the front is a guillotine blade — or your tomb, ha!”

Nancy’s first impression was dismay at the sight of a man she wasn’t sure she knew after so many years of marriage. Wyeth thought she hated it. But he had misinterpreted her; she admired it as a work of art, something far more significant than a portrait.

Andy had talked to me over the years about dozens of works but always refused when it came to the infamous Helga series. But in 2004, for a lecture in Omaha to accompany a traveling show of the Helga works then owned by a consortium of Japanese banks, I asked him to give me the vital interview and he consented. And the revelations are stunning. I was finally able to get his remarks of the important pieces published in Andrew Wyeth, Helga on Paper, a 2006 catalogue of a show of many of them in the Warren Adelson Gallery in New York.

Let the artist speak for he or she always knows best. As we used to joke at graduate school, “kunstgeschichte (art history) is horsegeschichte,” and so are many art historians, including me.

Previous Chapter – Next Chapter