To round out 1986, I wrote a mischievous and biting story, “Money and Masterpieces,” in which I compared the collections and the connoisseurship of two of America’s top museums and their directors, the Kimbell in Fort Worth and the Getty in Malibu. I concluded that despite the Getty’s advantage of having around eighty million a year for acquisitions as opposed to the Kimbell’s measly four million, Ted Pillsbury of the Kimbell was kicking Getty director John Walsh’s ass when it came to getting great works.

In preparing the story I had pored through the contents of both museums. The Getty’s then-curator of Greek and Roman art, Arthur Houghton Jr. (son of my former president at the Met), showed me a secret purchase, a rare Greek 6th century B. C. marble kouros, a handsome athlete made to please the gods. The huge sculpture was hanging on well-padded chains in the conservation laboratory, just having been pulled upright from its crate for the first time since arriving at the Getty. It had been acquired by a curator I knew well as a shifty, troublesome guy, Jiri Frel.

In the blink of an eye I knew the sculpture was a fake. I turned to Houghton and asked, “Have you guys paid for that?”

“Some kind of a joke?”

“Not at all. If you haven’t paid, don’t pay. If you’re buying on time, stop payments. If you have paid, get a lawyer.”

“How would you know anything? You’re not an expert in this field.”

“I am. I have excavated in Sicily at Morgantina and ancient pieces do not look like this. You’ll see.”

I then launched into a mini-lecture for Houghton and the associate curator, Marion True. Frel was out of the country. “It’s too pristine to be twenty-five hundred years old. The surface color — café au lait — is impossible. These ‘ancient’ damages seem to me to be very suspicious — dents on the hair but not on the face except for the carefully broken nose. The style is stiff, mechanical, especially the regular cascade of fourteen rows of hair; with those unpleasant, doughy curls in front of the brow. I can spot a number of styles present: one for the stomach and another for the feet. By the way, should an archaic sculpture have insteps? Pico Cellini, you of course know him, tells me he’s seen a photo of it in the process of being made, but I don’t need him for me to know it’s wrong.”

That was quintessential ‘Artful Tommy’ curating. Once I had developed my full stride — after Erich Steingraeber’s teachings — I could analyze works of art that fast.

Both Houghton and True, who came across as being short-tempered and arrogant, told me in effect I was nuts. I laughed and said, “You’ll see.”

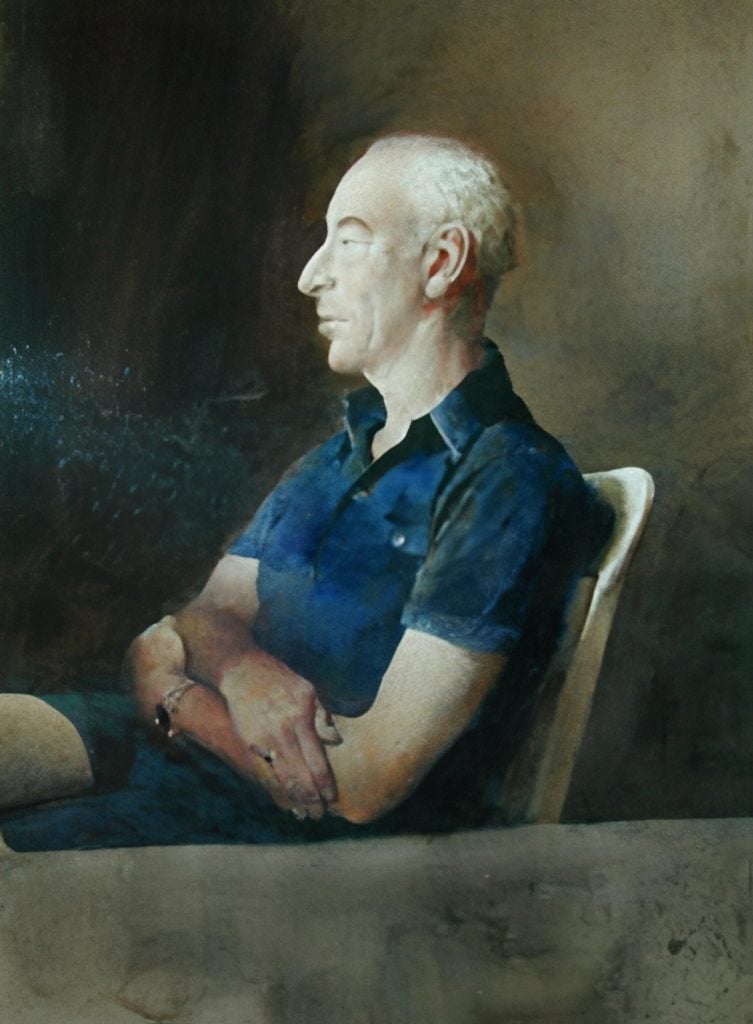

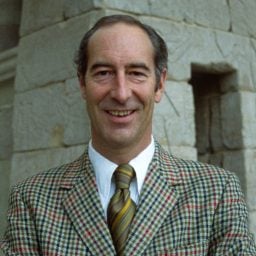

That same day I met Getty director John Walsh and told him of my suspicions. He is a tall, lanky guy with a serious, somewhat halting academic way of speaking. He had worked for me at the Met and had proven to be something of a loose cannon and a selfish idealist. During the fracas about a curators’ union he had picketed me and later had resigned in solidarity with his boss, the curator of the European paintings department. They had protested my sending to the Soviet Union a few paintings on panel, which they assumed, incorrectly, were too fragile to travel. When Walsh went on to Columbia we had made up; I had done him some minor favor and he had penned a warm hand-written thank-you note.

Walsh, too, pooh-poohed my opinion that the kouros was phony and explained that fourteen months of the most rigorous scientific examination proved that the light brownish patina on the marble could never have been produced by artificial means. He also said an “overwhelming number of specialists” had blessed it.

I asked for their names and he refused.

I asked where he’d gotten the piece and what its history was. Again he refused.

What a dumb, annoying guy, I thought.

I asked for a set of photos for publication and he said none were available. Talk about cooperating with the press!

Right then I decided to do a major story about the kouros and the Getty, which was clearly in need of better leadership. It was the opening skirmish in a war between me and the Getty Museum that would last for years and would seriously damage the Getty, and me as well.

But, did I care being damaged? Hell, no, I loved it.

I teamed up with Geraldine Norman, the brilliant salesroom correspondent for the London Independent. She had received from an anonymous Getty insider a packet of documents on the kouros: the identity of the dealer who had sold the statue to the Getty, Gianfranco Becchina of Geneva, his price of nine and a half million and a legal paper stating that any inaccurate information in Becchina’s provenance facts would allow the Getty to get their money back. There were also the results of the lengthy scientific analyses and letters of praise for the work from experts all over the world.

The battery of tests concluded that the marble — identified as having been quarried on the island of Thasos — was “dolomitic” in nature and over the centuries had “de-dolomitized,” a process said to be impossible to create artificially. I smiled, recalling how many of the Met’s scientific tests were frequently at odds with connoisseurship. Connoisseurship was usually the winner. The Getty tests of the kouros were faulty. It was, for instance, the first and only dolomite marble ever tested. There was no existing body of data on marble that could be used as measuring sticks, unlike, for example, hundreds of paint samples for old masters. As for the utter impossibility of any gnome-faker duplicating the centuries of “de-dolomization,” I later revealed in my book on fakes, False Impressions, the Hunt for Big Time Art Fakes, that a student at a local California college had been able to recreate the exact café au lait surface of the curious spurious Getty kouros.

In saccharine letters some of America’s loftiest experts in the field of archaic Greek art had drooled over the statue to Jiri Frel. One scholar even composed a panegyric in Latin. It must be said that few of the folks had been allowed to be alone in the room where the statue was shown — Frel was always in their faces — and the piece was never taken out of its crate. Looking down at a monumental sculpture can be misleading.

There were a number of other doubters besides me and Pico Cellini — Dietrich von Bothmer, Cornelius Vermeule at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts and one of the most dogged “fakebusters” of antiquities, Dr. Evelyn Harrison of NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts, and Federico Zeri, a confidante of J. Paul Getty’s and a member of the Getty Museum board of trustees. I tracked them all down.

Harrison wrote that she had expected to see a sculpture of northern style because the marble was surely from Thasos. Yet, she was shocked to see a mixture of styles from southern locales. For her, the killer argument against the kouros was that the back of the boy was older in style than the front — in every other kouros the opposite is the case. The reason is that ancient Greek sculptors experimented with anatomy on the backs of kouroi because in temples the backs were against the wall. She thought the knees looked summary and weak, almost as if the forger knew the legs would be discarded before the sale. Harrison gave a hilarious scholarly lecture starring the kouros entitled, “Making and Faking Greek Sculpture.”

Von Bothmer examined the statue long after it had been purchased and loudly expressed his doubts. Dealer Becchina heard about this and confronted him in Rome.

“What the hell do you, a vase expert, know about kouroi, anyway,” Becchina spat out.

Von Bothmer calmly answered, “A good archaeologist could look at a real kouros and tell everything about it — where it came from, its style, its date, etcetera. Let me give you a parable. If a student of mine in an art-spotting test is shown a slide of an English early Gothic-style church portal and if he sees off to the side a sign saying, ’Eintritt,’ well, he might have doubts that the church really was English, wouldn’t he? All the stories I have heard about the provenance of the kouros are fairy tales. When you tell me where it came from and where it has been all these years, then I shall be delighted to discuss the style and everything about it.”

Federico Zeri had been at the board meeting when Frel has made his pitch to buy the kouros. He told me: “Frel kept dancing around what he called ’the greatest example of ancient art of the 6th century before Christ in the world.’ He kept on telling us that the statue was an incredible bargain at a mere twelve million dollars.

“My first impression was that it was not so bad, then the more I looked the more doubts began to come to my mind. The surface was strange — the color like tea. As you, a detective of fakes, knows when something is no good, a tiny detail will become an enormous red flag. In this case it was the fingernails; they were so amazingly natural in the way the nails met the cuticles, far too naturalistic for something of the sixth century B.C. I was bothered, too, by an inexplicable fault in the marble at the side of the face and in the hair right in the middle of the forehead. I suspected that a flawed piece of stone had been used — and this would have been impossible in ancient times since the statue had to be perfect or the gods would get angry.”

Zeri had blocked the purchase for a few board meetings despite the fact that the chairman of the Getty Trust, Harold Williams, pushed uncommonly hard for its acquisition. Williams was the former head of the SEC and before that Norton Simon’s partner and lawyer. After Frel haggled the price down from eleven million to nine and a half and once Williams had forced Zeri off the board after the scholar had ill advisedly mentioned the top-secret statue in a radio interview, the kouros was acquired.

Our Getty insider sent Norman a series of letters from the confidential files “proving” that the statue had been in the possession of a certain Dr. Jean Lauffenberger of Geneva. But after a brilliant investigation, Norman showed that the sculpture had never been in the doctor’s collection and that many of the letters attesting to that fact were bogus — letters sent by scholars from different countries over a few decades had been written on the same typewriter. Two of Lauffenberger’s ex-wives had never seen the one-ton, six foot nine inch tall statue in his collection. Nor had any of his closest friends.

When the Getty put the kouros on exhibition their publicity department persuaded the New York Times art critic, John Russell, a deft writer but no expert in classical antiquity, to write a front-page story on the “treasure.” He did and it was nothing more than a Getty press release. He called it one of the finest acquisitions ever made by an American museum in any field. Russell chided me for my doubts, writing, “the faker would have had to be a person of great historical sensitivity and familiar with the sculpture produced in the Greek island workshops in the 6th century B.C. He would have to be a carver of genius. He would have to be able to outwit forms of scientific analysis that have been developed only very recently. And he would have had to be a crook.”

“Spot on!” Geraldine Norman cried out.

The Russell piece was the beginning of a non-stop Getty PR onslaught against me. A second-rate Los Angeles art critic, who had been a ceaseless defender of the Getty and Jiri Frel, assailed me as being an admitted pathological liar (I had written that I occasionally told a white lie in one of my books). The New York Review of Books roasted me. In Vanity Fair I, not the kouros, was singled out as the “fake,” by a staff writer usually assigned to celebrity puff pieces. In that article Marion True was praised to the heavens and quoted as saying that I knew nothing about art and only wanted to sell magazines. The English magazine, Apollo, published an editorial against me, “Let’s Not Be Beastly to the Getty.”

The Getty publicists hinted that I was after John Walsh’s job. To which my wife tartly replied, “Director of the little Getty after the Met? Come on! Besides, exposing a costly fake is a hell of a way to send a resume.”

The roasting didn’t bother me all that much — after the criticism I had received during my Parks Department and Metropolitan days this was mere nattering. Plus, I knew that in time my critics would know I had been right — not that they would ever admit they were wrong. When asked by one writer if I would investigate the Getty further I was quoted as saying, “This is the itty-bitty beginning.”

Then the “finest acquisition in the country” crashed.

How it happened is yet another wacky tale for which the art world is famous. In 1990 an English antiquities dealer, Jeffrey Spier, found in the shop of a Basel antiquities gallery a headless marble torso with the legs knocked off at the knees. It was all but identical in style to the larger Getty kouros but was one-third the size (probably a trial piece the forgers had made before cutting into the larger and far more expensive marble). Spier immediately told Marion True, who came to see it. When she saw the connection she said, “I felt like someone had kicked me.”

I got the news on a sailing weekend over the fourth of July weekend on Lake Champlain with my wife and daughter on board her then boyfriend’s hot Swan racing machine. I was having a leisurely breakfast and the skipper tossed me a copy of the Burlington, Vermont, newspaper.

“MUSEUM’S STATUE MAY BE FAKE. The J. Paul Getty Museum in Malibu has removed its prized Greek ’Kouros’ statue for study because of new doubts about its authenticity. The marble sculpture of a young man, thought to date from the 6th century B.C., is one of the museum’s three most celebrated Greek antiquities. The Los Angeles museum purchased the ’Kouros’ in 1985 after 14 months of study and put it on view in 1986. But a recent discovery of a marble torso considered to be a forgery has raised new questions about the Getty statue. That torso is made of similar marble and contains many similarities, Getty officials said.”

I phoned Norman in Cambridge and she laughed heartily.

I called Arthur Houghton who tried to back-pedal, saying that he had been suspicious of the kouros all along. Of course he hadn’t been. Then Houghton told me something I thought summed up the unethical nature of the Getty’s Greek and Roman department and John Walsh’s administration. In the spring of 1986 during his investigation of the provenance of the kouros, he had found out that the signatures of one key scholar, Ernst Langlotz, who claimed to have seen the kouros in Dr. Lauffenberger’s collection, were bogus. He had also found out — and had told Walsh — that a letter from some Swiss dealer asking Lauffenberger to sell his kouros was also bogus.

Walsh’s initial reaction to the news of the cooked provenance papers was to moan that he’d landed the plum museum job in America and now his debut would be a disaster. Walsh angered Houghton by demanding that he stop investigating the statue.

Houghton told me something else astonishing. Marion True, when confronted with Houghton’s evidence, reacted with “’an amused shrug.” That meant that True knew that the provenance file had been cooked when she told New York Times art critic Russell that the provenance could be established as far back as “fifty years.” So did John Walsh. Houghton had composed a letter to Walsh outlining his beefs about Walsh’s outrageous professional conduct and his feckless management of the museum. He followed up with a letter to Getty Trust chairman, Harold Williams, telling him everything. He then resigned.

In “My Eye” I wrote: “In an act of no little courage, the Getty Museum announced in July that its prized sixth-century B.C. athlete, or kouros, had been taken off exhibition and sent back to the lab for further art-historical and scientific tests, owing to fresh new doubts about its authenticity. According to the antiquities curator, Marion True, a modern torso has surfaced in Switzerland made out of the same stone, possibly from the same quarry, as the Malibu boy. The two statues, True said, have more in common with each other than with any kouros of indisputable authenticity in Greece. In 1984 the museum carried out a battery of scientific tests, which the Getty said proved conclusively and positively that its marble kouros could not have been aged artificially. The Getty now says that these tests are ‘not valid.’ I am not surprised.”

Not long afterwards I was told that someone overheard someone in L.A. saying, ’Hey, that Connoisseur guy was right after all!’

The Getty bought the smaller statue for research purposes. To my knowledge the museum never asked Gianfranco Becchina to return their nine and a half million bucks, which they had every legal right to do. They changed the caption accompanying the kouros in the coffee-table book of the Getty’s prime treasures to “Either sixth century B.C. or 20th century.” When the refurbished Getty Villa of antiquities opened in 2006 the cloddy thing was displayed, but with all the doubts aired on wall labels. Today there’s hardly a scholar who does not agree with my assessment. In 2005 the New Yorker writer Malcolm Gladwell published a best-seller, Blink, and memorialized that flashing instant reaction of sheer disbelief when I saw the curious, spurious kouros for the first moment.

At the meeting with John Walsh when he had refused to give me any information about the kouros, I had asked him about the status of curator Frel, who I heard had been ousted.

Walsh gave his most sincere look and intoned, “We have no troubles with Jiri. He’s probably our most valued senior research curator. He works for us in Europe.”

“Sort of up and out?”

“Nothing of the kind.”

Walsh was obviously lying, which really pissed me off.

“How can I reach him?” I asked.

“That is confidential,” he spat back.

Again I thought how silly of Walsh. It took me a day to learn where Frel was living just outside Paris and with whom.

I knew Frel all too well. He had worked for me for a spell at the Met. In fact I had saved his neck when he begged for a job because he was about to be sent back to Communist Czechoslovakia after the collapse of the so-called Dubcek Spring. I had hired him to work in the Greek and Roman department under Dietrich von Bothmer and secured for him a Nansen passport, an international identity and tourist card invented in 1922 for stateless refugees. Jiri had spurned American citizenship because of his love for mother Czechoslovakia, or so he said. The Nansen has one benefit no other passport possesses, with it no one can be extradited to another country.

We signed a contract with Frel and he broke it in a year, claiming that his asthma forced him to work for the Getty Museum, which, he pointed out, was at sea level. I laughed, “Malibu is not lower than Manhattan.” But, since he had already seduced Paul Getty to hire him, I let him go.

Frel was to be my guide at the 1974 opening of the Getty Museum in Malibu. I was taken aback when showed me a staggering number of “hot” pieces, obviously smuggled out of Italy. He retorted, “The Italians are too dumb to recognize them and, anyway, they are all from that great Hungarian noble collection, Count Esterhazy’s. Tom, I have come up with a trick; I have arranged that we are the ’innocent’ third party in any purchase of antiquities.”

He was a bit high on wine and suddenly launched into a shocking tirade about the “ignorant” Getty trustees. “They are nothing but incompetents, California thugs and idiots and intellectual cripples. I hate the fucking crowd and I shall show them.”

After meeting with Walsh, I asked Geraldine Norman if she knew why Frel had been exiled to Paris as a research curator. “Something about donations. Tom, why is it that Frel’s department made more acquisitions than any other and most of them are gifts?”

“Gifts — to the super rich Getty? I’ll take a look.”

“Start with the Getty Journal for 1984 where a host of Greek and Roman works are listed.”

Norman also urged me to talk to Zeri and I flew to Italy to see him. The elegant professor lived just outside Rome and had a way of erupting in the middle of a conversation when he disliked something. He became positively “Vesuvian” about the “crook Frel” and, after telling me his opinion about the kouros, described how Frel had bought several fakes other than the kouros and pushed the trustees tirelessly to acquire others. One fake was a marble head supposedly by the 4th century B.C. Greek master, Scopas, who had carved some highly emotional, realistic heads for a temple in Tegea. Another was a fragmentary relief showing a warrior binding up the head wound of another. The ones he’d pushed the Getty board to buy but were vetoed by Zeri, were a 5th century B.C. funeral relief showing a chap holding a flower and a sarcophagus with what Frel described as the only depiction of the Lighthouse at Alexandria, but which Zeri pointed out was a modest Roman item with the commonly-represented lighthouse at Ostia Anticha.

What the hell was Frel up to?

Within ten minutes after I got my hands on the 1984 Getty Journal I knew what my old buddy Jiri had been doing — routinely over-inflating the value of gifts for their donors. With the help of a seasoned researcher working for the magazine, Helen Howard, I devoured all the Getty journals and the Getty Trust’s PF-990 tax forms. We found that from 1973 until he departed in 1984, Frel had accumulated the world-record of gifts — 6,453 antiquities ranging from potsherds to marble heads and statues from over a hundred donors evaluated at $14,441,228. That amount included $1.7 million for potsherds alone, something as cheap as shells on the beach! In the ten years I directed the Metropolitan that was more gifts than all twenty departments put together had managed to attract.

He had either himself evaluated the gifts or had persuaded others do it. Norman, using her salesroom sources, found one piece he’d bought for around six hundred dollars at Christie’s and had valued it for gift purposes at forty-five thousand. We were eventually able to name half a dozen such examples.

One European dealer told me how Frel worked. He would fall in love with, say, some black-figured vase and ask the dealer to triple the price explaining that the Getty board would only buy expensive pieces. To Frel, a work was important to the “idiot Getty trustees” only if it was astronomically expensive. Then Frel would ask the dealer to throw in dozens of lesser items or hundreds of potsherds for free. These would be shipped to Bruce McNall’s Summa Gallery on Rodeo Drive in Los Angeles and Frel would then pass them out to his favorite donors or would simply put donors’ names on the items and then accept them as gifts for the Getty.

Was the scheme crooked? I couldn’t figure out how. If Frel had personally made evaluations that was a serious breach of museum ethics, but not something illegal. If certain donors got a deduction from over-inflated values, that was a problem between the donor and the IRS, not Frel.

The odd thing I found was that thousands of the gifts had never been paid for by either the donors or the Getty. I called twenty or so of the hundred or so donors and discovered to my puzzlement that only a few had bothered to apply for tax deductions. Five donors had no idea that they had given gifts to the Getty. Bruce McNall, the owner of the Summa antiquities gallery and his scholar wife, Jane Cody, were appalled that Frel had used their names on objects given to the Getty — they had never seen the pieces, or so they said. Another donor, a Hungarian, told me his gifts were part of a large collection of antiquities he’d dragged out under the wire during the Hungarian revolt. When I asked him what was his favorite piece in his entire holdings, he couldn’t remember. The guy happened to be a car dealer who had “loaned” Jiri a vehicle.

One donor explained that Jiri was a “passionate collector who simply wanted a study collection for the Getty and the trustees were reluctant to give him funds to acquire the lesser items.” Of course I didn’t buy that story.

I did dig up one intriguing lead that indicated Jiri was on the take and loved money despite acting and living like a slob. A lawyer with whom I had worked in the Lindsay administration told me that Frel had assured him he could buy his collection of antiquities for the Getty for half a million dollars without board approval if ten percent in cash would be paid up front to Frel. But the lawyer refused to allow me to use his name and I never published the story.

Then, some time after our articles spelling out what Frel had done were published in Connoisseur and the Independent, Alain Tarica, art dealer, theoretical mathematician and expert on fakes, explained to me what Frel had been doing.

“The scam revolves around the fact that the value of his fakes and the value of the gifts are virtually identical, fourteen million four hundred thousand dollars. This is purely and simply a money-laundering scheme and has nothing to do with American donors getting tax deductions nor with Jiri getting kickbacks from donors. The $14.4 million the gifts were worth is a ’vacuum’ in which ’black’ money could be poured. This con game of Frel’s has to do with Swiss tax law and the dealers who had sold Frel the fakes.

“Take the kouros. The Geneva dealer Gianfranco Becchina buys the kouros for, say, $100,000 and sells it to the Getty for $9.5 million. He gives Frel, say, $4 million, which Jiri deposits in his Swiss bank. Since Frel’s not living in Switzerland, he pays no tax. Becchina, who does, tells the tax authorities he sold the kouros for nine and a half million but in order to close the deal with the Getty he had to buy antiquities worth, say, $5 million from a Panamanian art corporation, and these things went to the Getty as gifts. So, Becchina’s profit is $4.5 million and he pays only $2.25 million in taxes. That’s the only way to explain why the value of the gifts and the cost of the three major fakes is the same — $14,441,000. And this also explains why some of the donors had no idea they’d given anything. The only point is that Frel got over six thousand gifts evaluated at $14.4 million — and it doesn’t matter if some donors got inflated deductions or knew or didn’t know about the gifts or didn’t. It’s a classic money-laundering scheme. Frel worked it out with Becchina and the other vendors of the fakes.”

The theory was substantiated in 2006 when it was revealed by the Carabinieri that a copy of Frels’ passport and other documents proving a partnership between Frel and Gianfranco Becchina, were found in the Becchina’s Sicilian home.

Geraldine Norman and I decided to interrogate Jiri. We tracked him down to an apartment outside Paris where he was living with his son, Sasha, and a young woman who was a librarian at the Louvre.

I borrowed a Parisian friend’s car outfitted with a phone. When we arrived at the housing complex, I phoned Frel’s number. A woman answered and told me he would be away for some days. Certain he was in the flat, I knocked on the door and although I chatted for a while with the woman behind the closed door, I wasn’t allowed in. I sensed Jiri’s presence. In the parking lot I happened to spot a very fancy white Saab Turbo Commander with Swiss plates. On the dashboard was a letter addressed to Frel.

I phoned Alain Tarica and he told me to give him the Saab’s license plate and he could track down the owner. Within an hour, Tarica had the information. The car was owned by a private bank in Geneva. Tarica had reached the vice-chairman of the bank, a woman, who first told him that she had loaned the company car to Frel so he could sell books to French libraries — the bank owned a book distributing company.

When Tarica asked for data on the book company the woman confessed that she and Frel were having an affair. We researched the bank and found some odd things about it. It was Frel’s and Gianfranco Becchina’s bank as well. In 1983 when Frel had been “exiled” to Paris, the Getty had deposited fifty million dollars into the bank and a year later withdrew the funds. We could find no PF-990 record that the Getty had made any money from the deposit. Could the interest from the deposit have been a pay-off to Frel? I think so.

After our failed attempt to come face to face with Frel, we heard from inside the Getty that Harold Williams, John Walsh and Marion True (who had just been named curator of Greek and Roman antiquities) were beginning to feel our heat. We decided to go to California and confront the three of them.

Just before leaving I received a call from the conglomerateur and art collector, Norton Simon. During my Met days he had suggested that I build a Simon museum-within-a-museum inside the Met to house his excellent collection, parts of which would be continually lent out to institutions around the globe.

I had met or talked to Simon five or six times. Once on the phone he spoke to me in a bizarre falsetto, explaining, “My shrink wants me to break free from my macho, commanding voice.” But this time his voice was strained and tired. He apologized, saying he’d suffered a stroke.

“Are you committed to being the editor of Connoisseur?” he asked. “I would like to buy the magazine; would you have any trouble with that?”

“Maybe the Hearst Corporation would. I’ll get you the number of the chairman, Frank Bennack, and you can talk to him.”

He called several more times to chat about his desire to buy the magazine and his intention to stuff it with ads. He gave me his “super-private”number and asked if I ever got out to California to reach him for a “meeting for mutual interests.” I told him that I’d be there the following week.

I called him as soon as Norman and I were ensconced in our Santa Monica hotel. I had her listen in on a second phone and take notes.

“I am trying to work out a deal between the Getty and you,” Simon said. “The possibility of buying Connoisseur and you being the head guy here. We’d make a commitment on ads and other ways to support the magazine. And we’d make some editorial changes, too, especially about the Getty.”

“Who’s ’we?’”

“Me and the Getty. If I go to Harold Williams and say so, he’ll support what I want. Your pay would not be money alone; it would come in other, positive means. We’ve talked about how southern California can become the world art mecca. That’s it. You will be the head guy. The Getty has a few billion now. And may never get old masters except through me. A positive series of things. Getting our minds together.

“Williams has been having trouble with Walsh,” he continued. “Despite the fact that you’re known to be a little wild and universally hated by the Getty for the stories you’ve written, you are recognized as someone with executive experience and, of course, your great ’eye’. I’ve been thinking that the Getty ought to buy some of my finest old masters — where else are they going to get them? We bought two pictures together once. I want you and Harold to come here and talk about this.”

“Does Williams know anything about this?” I asked.

“I haven’t talked to him fully yet,” he said suddenly sounding suspicious. “I always tend to think in terms of a fantasy, Tom.”

“Norton, I can’t meet you. I am here with my colleague, Geraldine Norman, you know, my colleague from the London

Independent on the Frel expose. We’re here to ask Williams and Walsh further questions about the Frel scandals. Would you help in getting us an appointment to talk with Harold?” I didn’t want to meet Simon because my friend Walter Annenberg, when I told him of Simon’s bribe attempts, advised me never to meet him in his home. “He’s the Dr. Moriarty of the art world and he’ll tape your words, have them recut into a damaging story against you. He’s very, very dangerous.”

Simon said he would and soon called back to say that Williams was “very tied up.” I tried to reach Simon the next day at his “super-private” number and the phone was answered by an insurance company representative who swore that the firm had possessed the number for at least fifteen years.

That’s power.

Later when the New York Times reported on the follow-up Getty story Norman and I wrote for Connoisseur, Simon was quoted as saying, “What Tom Hoving told you about what we discussed is not the truth. Tom always tends to think in terms of fantasy.” The New York Times believed Norton Simon. Simon announced within days that he would donate all his art to UCLA. That was a ruse. Some years later he built his own museum in Pasadena and put the fake Rembrandt, Titus, on the cover of the catalog.

(Later on, for Cigar Aficionado, I was able to expose how Simon had manipulated the value of his collection by selling works from one of his foundations to another and then re-evaluating his entire holdings upwards. He did this every year and eventually re-evaluated his collection from the millions to hundreds of millions. He had also taken for himself all the works that his shareholders had purchased. Every year he would change the name of a company art foundation to a different Norton Simon foundation. In time there were a half dozen foundations. Then, just before a hostile takeover, he collapsed all the foundations into one, naming it The Norton Simon Art Foundation. The supposedly sharp New York lawyers handling the takeover failed to discover that all the art was not owned, in fact, by Simon but been bought by the shareholders and was company-owned.)

Norman and I sent to Harold Williams thirty-eight questions, including what kind of investigation had the Getty trustees undertaken about Frel or what had their probe revealed about his “criminal activities.” (Zeri had told us that Harold Williams had informed the board that Frel was leaving because of “criminal activities”). Had the IRS been informed of Frel’s doings? How did the museum account for the fact that some fifty antiquities given to the museum between 1973 and 1983 were not listed in their mandatory tax filings?

Williams wrote us that after a lengthy investigation with outside lawyers, Frel had been relieved of his post in April of 1984 for “serious violations of the museum’s policy and rules regarding donations to the antiquities collection.” Williams called him a “distinguished scholar” and stated flatly, “There was no evidence of personal financial gain on his part.”

To me this was a typical spurious Getty in-house probe. And further proof that the feckless John Walsh had lied to me repeatedly.

Then Norman got an unexpected call from a near hysterical Federico Zeri saying that Frel was trying to buy for three hundred and fifty thousand dollars an apartment owned by one of Zeri’s close friends. Zeri had gotten the address of the small flat near the Pantheon where Frel was then living. I happened to be in Europe, so I called Patricia Corbett to join Geraldine and me for a stakeout.

Frel emerged at last from his apartment several days after we began watching the place, lounging around on car bonnets. He began to curse when he spotted Geraldine Norman, screaming that she was “an unprincipled gossip writer, who has ruined my life.”

We interviewed him for two days over lunches and finally at dinner. He refused to say much about his deals or the kouros except to say that he had been poking around small islands and villages all over Greece trying to pin down the history of the statue. When Geraldine told him that the Lauffenberger documents were bogus and that none of Lauffenberger’s wives or closest friends had ever seen the kouros, Jiri grinned impishly and said, “I saw it at the house of his mistress.”

I brought up the other fakes — the Scopas head, the Wounded Warrior and the ones Zeri blocked him from buying and asked how he, an expert on archaic art, could possibly have been fooled. Enraged and by this time drunk, he grabbed a full glass bottle of mineral water and swung it at my head. I ducked. He then slammed me painfully on my shoulder. I asked Geraldine to leave the restaurant with me but she stayed. Later she decided not to accompany him up to his flat.

The only thing he said to us over and over was, “What I really did was bigger than they know.” Frel died in May 2006 without revealing anything. Yet, he didn’t have to, for I had nailed the crooked son-of-a-bitch who had so sullied the Getty and the entire museum profession.

My war with the Getty continued. On June 22, 1988, I received a phone call from an eminent New York antiquities dealer.

“I just got a call from Marion True and she tells me that the pieces I have had out there at the Getty for six months at least will not be considered because she’s found something world class and as important as a Parthenon sculpture and had to bundle all the funds available to her department to get it. I am furious.

“I asked her to tell me what it was and she did. Hell, I know the piece! It was offered to me last year. It’s a seven and a half foot or eight-foot tall limestone sculpture of a goddess, I was told Aphrodite or Demeter, dating to the golden period of 425 to 400 B.C. just after the Parthenon. I was offered it for one million by a Sicilian art dealer working out of Geneva. There’s a marble head, too. The drapery is thick and swirling and pretty damn fine. But I turned it down.

“Marion told me that it cost them twenty million and so her department has spent their funds for the next year or two. She was ecstatic and didn’t seem to get it that I’d be miffed that my things had been there for examination for so long and were now never going to be bought by the Getty. I commented that maybe such a piece would cause trouble with the Italian authorities. She boasted that she’d ’pulled the wool over the Italians eyes’ on it — those were her exact words. She sent them photographs asking if the Italians had ever seen it. Of course they said, ’No,’ since it was dug up illegally and smuggled somehow to Geneva.

“The dealer in Geneva told me that it was from Morgantina. It’s provincial but grand. Too grand! I have a rule, my ’three-foot rule.’ I never buy anything that’s over three feet tall unless the piece happens to be smaller but in precious metal. Anything over three feet is inevitably going to enrage the country from where it was smuggled and I don’t need that sort of hassle in my business.

“I am furious and want you to look into this and publish it in Connoisseur. Hell, you’re the only publication that’s been courageous and straight about the Getty and its messy antiquities acquisitions. But do not mention me. If my name comes out my business will be severely damaged. Promise?”

“I promise.”

I alerted my team of investigators — Susan Pettit in Los Angeles, Patricia Corbett in Italy, Paul Chutkow in Paris and Michael VerMeulen in London.

Pettit, a crack reporter with the instincts of a seasoned detective, went to L.A. Customs and found that on December 15, 1987, a crate, sent from Britain and weighing a ton, arrived on a TWA plane. The declared value of the Greek statue was $20 million. The name on the declaration was the London antiquities dealer Robin Symes. The crate was trucked to the Getty Museum. Inside was a mammoth limestone sculpture of a wondrously draped female form — a goddess, perhaps Aphrodite.

“Do you want me to go to the Getty and ask them about it?” Pettit asked me. “My only worry is that they’ll go to ground in that castle of theirs.”

“Go ahead rattle their cage. We’ll see if any shit drops out of it.”

She soon got back to me, “The Getty just raised the drawbridge.”

Pat Corbett talked to Robin Symes about the piece and he denied having heard of it. Corbett then remarked, “Then you’ll want to know that an imposter signed your name to a Los Angeles customs declaration for this goddess with an evaluation of twenty million.”

He choked and slammed down the phone.

Corbett went to the individual at the Ministry of Culture in Rome in charge of antiquities and learned that the Getty had contacted him in the summer of 1987 with a description of a large limestone female sculpture, asking if he had heard about it or seen it. He had sent the information out to various superintendents of antiquities but for some reason omitted the superintendent for Agrigento, which deals with Morgantina. No one had heard anything about the mammoth statue.

After Pettit had rattled their cage, the Getty dispatched Malcolm Bell, an archaeologist from the University of Virginia who had worked at Morgantina for some years, to see Graziella Fiorentini, the antiquities superintendent of Agrigento. He showed her photographs of the Aphrodite and said that the Getty had heard “press reports” linking the piece to Morgantina.

When Pat Corbett went to visit Fiorentini a few days later, the superintendent informed her that when Bell had mentioned Morgantina her mind raced back to 1978 and 1979 when she was overseeing the Morgantina digs. She recalled hearing rumors about the clandestine discovery of an exceptionally large marble or stone sculpture. She was skeptical because Morgantina was known for its wealth of terracotta statues. (Amusingly, the ones I had found in my goddess gusher).

She asked Marion True requesting for more information. True cabled back that there’d been a misunderstanding — there were no “published” press reports of the statue’s coming from Morgantina, the Getty merely wanted to know if Agrigento had any specific information about it.

“I was unsatisfied,” Fiorentini told Corbett. “The Getty was asking the wrong questions. If the piece were legitimately on the market, it should have all its papers in order — but it didn’t. How could I give her the go-ahead she was asking for?”

She cabled True on July 21st saying that the local and national police were looking into the possibility that the Aphrodite had been illegally excavated and exported.

On July 28th the Getty hastily put the piece on view. When asked why so suddenly, the Getty flacks said, “in order to be certain that if there were valid claims to be made, they would be made promptly.”

I had a good laugh at that. As I told Susan Pettit, “I suppose they could not have said that damned Susan Pettit of Connoisseur forced their hand.”

We had also heard from my antiquities dealer source that an additional marble head and two hands — so-called akrolithics, or marble inserts to a limestone statue — were on loan to the Getty from Robin Symes. They were also probably from Morgantina. Susan visited the Getty and saw them. The next day when she inquired about the pieces, they were quickly removed from exhibition and vanished — probably back to Robin Symes.

John Russell, the gullible New York Times art critic who had so loved the fake kouros, wrote the news story about the acquisition and exhibition of the Aphrodite.

“The J. Paul Getty Museum has acquired for an undisclosed price an over-life-size Greek cult statue, believed to represent Aphrodite, the goddess of love. Probably dated around 420 B.C., the statue stands 90 inches high and is remarkable for the power and monumentality of the huge heavy limbs, the lightness and delicacy of the windblown draperies and the majestic serenity of the head.

“A composite figure, executed partly in Parian marble and partly in limestone, it is believed to have been made in southern Italy, which at the time was a Greek colony and part of Magna Grecia. It is the only known cult figure from the late fifth century B.C. that has survived largely intact from head to foot. Both for this reason and on grounds of quality it has aroused exceptional enthusiasm among scholars.”

Not every scholar was enthusiastic. Brunilde Ridgeway of Bryn Mawr called the Getty “irresponsible” for having acquired the unprovenanced piece. And archaeologist Joseph Carter of the University of Texas stated, “The Getty is making life very hard for American archaeologists. They are just like the nineteenth century robber barons.”

Pat Corbett called me with a hilarious new wrinkle. “The Getty’s Roman lawyer, Marco Gallivotti, got in touch with Fiorentini and told her the ’Aphro’ has been in the collection of a British antiquities merchant for fifty years.”

My London reporter, Mike VerMeulen, asked the keeper of Greek and Roman art at the British Museum what he thought of that. “Fifty years!” snorted keeper Brian Cook. “That takes us back to 1938 — and that rules out everybody I know. I cannot think of anyone active in London now who was active before the war.”

VerMeulen talked to an official at Spink and Sons, formerly a very active antiquities dealer, and he said, “It has to be Robin Symes.”

Pat Corbett reached the Italian lawyer who suddenly had a slightly different tale to pitch. The statue had been in an English collection since before World War II.

I attended a seminar in Taranto on the problems of smuggled antiquities, brought up the big Aphro and mentioned the names of Orazio di Simone, the dealer and smuggler who had shown my source the statue, and di Simone’s side-kick, Nicolo Nicoletti. Pat Corbett had come up with the names. The Carabinieri grilled them but came up with nothing. I contacted one of my Morgantina workers, asking if he knew about the statue and he told me that such information was too dangerous to talk about. Yet, he didn’t deny it had come from the dig.

In July, just after the statue’s unveiling, in the International Herald Tribune under my French correspondent Paul Chutkow’s by-line, we published our evidence that the Aphro was taken illegally from Morgantina.

Later in the October 1988 issue of Connoisseur — in a new department called Ethics — my article appeared under the heading “The Getty’s Statue: Beyond Legality.”

“Imagine that you are a high official at a museum that is long on funds but short on masterpieces. Imagine further that your last major acquisition, an imposing and unusual work, has been widely disputed; it seems, embarrassingly enough, to be a fake. To regain lost status, you would be on the lookout for a great piece, one that no one could disparage, and damn the cost! And if the work were bigger than life-size, well, that would be a definite plus — all the better to make a strong impression. Now, then, how far would you stretch the law to get it?”

The article caused a huge fuss at the Getty and throughout the museum world and among newspaper and magazine writers who loved the Getty and loathed Connoisseur and me.

In a Vanity Fair piece on the Getty, Marion True dropped a bit of acid on me, “It’s a great irony that of all the people out there he [Hoving] should be the crusader. The truth is, he’s constantly monitoring every move we make. If he can’t be the director in here, he’ll be the director from outside. He’s set himself up as the external authority on what we should do.”

Right on.

The writer, Lynn Hirschberg, who can be excused for knowing nothing about the subject since her field was Hollywood, huffed, “just as there is a dim possibility — although there is no solid proof to back up any real claim — that the Aphrodite’s provenance was doctored and that the kouros is a fake. The accuracy or inaccuracy of Hoving’s assertions is only part of the picture; given Hoving’s history, it is his vehemence, his sudden moral fervor that is so striking and, finally, so galling.”

“Sudden moral fervor”? The writer had clearly not bothered to find out about my efforts with UNESCO in 1970 or my 20/20 piece on the Getty bronze. I loved it. I had become a crusader because now my allegiance was to journalism. Added to that I loathed the hypocrisy and crookedness of the people responsible at the tarnished Getty Museum.

In an entirely antic sub-chapter of the Aphrodite drama, Geraldine Norman was contacted by a guy who called himself Eddie Yule who swore he knew that the Aphrodite had been chopped into three pieces in order to muscle it on board a private yacht that sailed from Sicily to Nice where it was unloaded. He seemed to know certain details about the piece that indicated an insider’s knowledge. Geraldine made an appointment to see this Mr. Yule, but he never showed.

Before my article was published, I wrote a letter to John Walsh alerting him to what I had found out from the New York dealer who had tipped me off. He sent back a form letter suggesting that he’d look into the matter. Of course he never did.

Despite the growing opposition by archaeologists across America, the Getty continued to gorge itself on Greek and Roman antiquities with no provenances. After Frel, Arthur Houghton kept on grabbing stuff without any history that had clearly been dug up illegally and smuggled out of either Italy or Greece. He even admitted it in an in-house memo. He was responsible for acquiring prime pieces from the Maurice Tempelsman collection — some twenty million dollars worth — most of which had been purchased from Robin Symes. Director John Walsh and Getty Trust president Harold Williams did nothing about the situation, even though Williams in a memo mentioned something about the Getty being a kind of antiquities fence operation.

Marion True stuffed the museum to the gills with illicit acquisitions. She coaxed Lawrence and Barbara Fleischman to give part of their large collection and sell the rest — costing some twenty million. There were no papers or documentation on any single piece in that batch.

The Italians became edgier and edgier, feeling that they looked like suckers for not halting the illicit traffic and not doing anything to get their ancient treasures back. They started digging at a site on the periphery of Morgantina where the Aphrodite was said to have been found. They discovered a large pedestal, which fit the size and date of the piece. What they sifted out of the site has never been revealed.

The director after John Walsh, Deborah Gribbon, when asked by the Italians to discuss a possible program of returning certain items, stone-walled and infuriated the Italians by her unconcealed arrogance.

Then something happened in March 1995 that made Marion True start acting like a reformed drunk in establishing a new antiquities acquisitions policy at the Getty banning any purchases without solid provenance. She voiced her new pure attitude at various art conferences across the country.

People in the field wondered what was up. No one found out until the Italians were good and ready and that took several years. The Carabinieri had tracked down a vast smuggling ring in which dealer Robert Hecht and one of Hecht’s suppliers by the name of Giacomo Medici were principals. In March of 1995, with the aid of the Swiss police, they busted into the storage in the bonded warehouses of the Geneva airport where Medici kept his stash.

They found no less than seventeen thousand antiquities, copious files and over ten thousand Polaroids showing a wide variety of antiquities in various states, some at the site of the illegal excavation, others in fragments, some uncleaned, others partially cleaned, and still others partly pasted together. Arduously, in a task, which is ongoing, they matched up a quantity of Polaroids with works of art in private collections and museums across the globe. A vase in fragments in a Polaroid — and, voila, the same vase in a prominent case in the Getty Museum.

The Carabinieri targeted three primary institutions, the Met for the Euphronios vase, the Getty for the Aphrodite and eighty-one other works and a private collector, Shelby White, widow of investment mogul Leon Levy, who had gathered up a hoard of over four hundred Greek and Roman goodies of which 93 percent were without provenance. She and her late husband had funded the Met’s twenty-million-dollar galleries for Greek and Roman artifacts with the expectation that the Levy-White stuff would be arranged, oh so beautifully, in the bespoke galleries. White had sounded off several times against countries that insisted on keeping every antiquity for themselves.

In Medici’s files the cops found sufficient documentation to allow an Italian prosecutor to indict Marion True for conspiracy to smuggle illicit antiquities, a conspiracy that included Medici and Bob Hecht. No American curator had ever been indicted by a foreign country for such a charge. The shock waves in Los Angeles and indeed throughout the museum community were off the charts on the Richter scale.

The timing of the top-secret bust of Giacomo Medici in 1995 and Marion True’s 1995 conversion to collecting purity matches up perfectly.

After the Medici affair, the Getty’s antiquities division began to fall apart, just as I had predicted so many years earlier.

True showed up in court in Rome and denied all charges.

The Los Angeles Times, eager to nail the president of the Getty Trust, Barry Munitz (who followed Harold Williams) with irregularities in the handling of his expense accounts, assembled a team of young reporters, Robin Fields, Louise Roug and Jason Felch. When their story turned to antiquities, governance and other corruption, Ralph Frammolino joined the team and Fields and Roug moved on to other assignments.

Some Getty insider with the keys to all the files and passwords to all hard drives started shipping Felch and Frammolino thousands of pages of documents of the highest confidentiality. Many were about Munitz’s peccadillos, but more were about the Getty antiquities. In fact, the reporters received several CDs with the entire 40,000-strong antiquities collection with notes, photos and histories.

Felch, who started at the Times as a police reporter, called me in New York for an appointment as soon as he got his hands on the documents. “From what the internal Getty documents show, the reporting you and your Connoisseur team did 20 years ago was right on the money. Can you show me how you did it, and explain how museums really work on the inside?”

“Come ahead!” I shouted.

Felch is a lean and hungry-looking guy who has lots of common sense and the right dollop of suspicion. From Connoisseur I had kept every note, every fact-checker’s opinion, dozens of addresses of Getty players, a file three feet long of papers, which proved of some use to Felch even if they were old. But, better, I was able to explain how antiquities are found, how they are smuggled and how they are laundered before being offered to museums. I knew the people, the techniques and the dodges. Felch learned a very great deal.

The Los Angeles Times — mostly under the Felch-Frammolino by-lines — published several dozen stories and they were nominated for a Pulitzer, but were edged out in the final round.

Their articles caused a passel of resignations and an investigation by the California Attorney General. Trust president Munitz resigned. The chief financial officer resigned. Two trustees resigned.

The articles brought about a profound and indelible change in how antiquities are looked upon by American museums and private collectors who may think about giving them to museums as gifts. From the publication of the articles onward, no antiquity will be bought or accepted as a gift or bequest by a museum in this country without an absolutely secure provenance. No more “Esterhazy” collections or “owned by an English gentleman for the past fifty years.”

I was asked by the Los Angeles Times to write an open letter to the incoming Getty director, Michael Brand.

“A couple of months ago, I submitted my application to become the interim director of the Getty Museum. I suggested a tenure of just 18 months, because all I had in mind was reforming its troubled antiquities division.

“I thought I knew how to do it, for I’ve been a bad boy and a good boy in the antiquities game. My track record as a curator and then director the Metropolitan Museum in New York ranged from being a rabid collector, willing to grab anything even if I suspected it had been smuggled, to a reformer who helped draft the landmark 1970 UNESCO convention against the worldwide smuggling of cultural patrimony. (The U.S. signed on to the convention in 1983.)

“Now the Getty clearly needs reform. Antiquities curator Marion True is under indictment in Italy for conspiring to receive stolen artworks and the museum’s own lawyers figure that possibly half of its top 150 masterpieces of Greek and Roman art were smuggled out of Italy or elsewhere. [The lawyers’ figure later soared to 300.]

“My offer was pleasantly turned down. The Getty already had an interim director; it was shopping for someone fulltime. Now that that person is on board — the resolute (we hope) Michael Brand. I’d like to pass along to him what I was planning to do in my first day on the job.

“First, I’d start settling with the Italians, even though the Getty is proclaiming its innocence and supports True. True’s trial is coming up in November. The Getty Trust has hired the most expensive lawyer in Italy and he ought to be able to cut the proper deal.

“Part of that deal should be a resolution passed by the Getty Board of Directors pledging never to buy, or receive as a gift or bequest, any antiquity unless its ownership record — its provenance — is squeaky clean. Over the years, the Getty to its credit has had versions of this policy in place, but none worded as strongly as this. Fact is, unless an Ancient Greek or Roman artifact can be proven to have been bought by Lord So-and-So on his grand tour in the mid 18th century and shipped to London, it has to have been excavated illegally and smuggled, out of Italy (or Turkey or Croatia), where laws protecting cultural patrimony stretch back to the 1930s.

“That doesn’t mean a vague notation that the piece comes from a source like the “collection of Count Esterhazy.” That was the provenance that long-gone disgraced Getty Greek and Roman curator Jiri Frel once boasted to me he’d cooked up for most of his hot statues and pots. And just publishing that an antiquity has an “unknown provenance” doesn’t cut it, either. It may not be possible to prove that a piece with little or no documentation was stolen, but that’s not the same thing as proving that it’s legal.

“The Italian authorities have stated they only want to stop the future illegal acquisitions of their patrimony by wealthy institutions such as the Getty (more museums and collectors may be indicted in the near future.) They claim they don’t want pieces returned. So far. But when they see a photograph of some Roman treasure in the Getty (“provenance unknown”) paired with a photo of the identical work, seized from a known Italian smuggler, they’re bound to get grabby and insist that it be returned. The Getty should cut them off at the pass.

“At least one major piece should be returned quickly. The Italians won’t cry out for the return of hundreds, I can assure you. They just want their bruised pride soothed. Top on my list would be the gargantuan (and oddly clunky I think) Aphrodite that was evidently found in 1979 or so by “tombaroli” in what was ancient Morgantina in Sicily (near the sleepy town of Aidone) and sold to Orazio di Simone of Geneva and thence to Robin Symes (the once-eminent now-discredited antiquities dealer of London and recently jailed for fraud now living in Geneva) and thence for $20 million to the Getty, thanks to Marion True.

“Another piece to be sent back — but this one only as a special two-year good will loan — should be the famous 4th-3rd century BC sculpture of a male athlete, known as the Getty bronze. This was found by the crew of the fishing boat Ferruccio Ferri from Fano, Italy in the 1970s, deposited in the bathtub of a local priest, then shipped out to a South American monastery labeled “concrete” and thence to Heinz Herzer, the Munich antiquities dealer who offered it to J. Paul Getty for $4.2 million. Paul Getty worked with yours truly to buy it for a maximum of $4 million but only if the dealer obtained permission from the Italian government. This never happened. After the old man’s death, Frel bought it for the full price without the permission. On a technicality, the highest court in Italy dismissed charges that the piece was smuggled.

“So the Getty Bronze should be loaned to Fano for two years in exchange for a loan something of equal importance, say, one of the two 5th century BC bronze warriors found near Riace, Italy, and now housed in the National Museum in Calabria. Every two years the Getty would loan another of its questionable treasures to some worthy institution in its country of origin, in exchange for something totally legit.

“I’d order the publication on the Getty web site of the complete inventory of the antiquities division including all facts (and horrors) of acquisition — along with measurements and photographs.

“I’d suggest, too, that Marion True undertake an exalted new role in research curatorship and then I’d start the search for a new department head.

And on the second day. . . .

Not much more than a week after my Op-Ed piece appeared, Marion True resigned because she’d failed to disclose enough information about a four hundred thousand dollar loan given her to buy a swanky home on the island of Paros (where the marble came from for the head of the Aphrodite, ironically enough) by Robin Symes’ partner. When she couldn’t get a mortgage from an American bank for that Greek loan, she accepted four hundred grand from Getty trustee, Barbara Fleischman, who had just sold True tens of millions of dollars worth of unprovenanced antiquities.

Then Barbara Fleischman resigned and both women never made it to the grand opening of the new Getty Villa overlooking Malibu beach where all the antiquities are on glorious display.

True still professes her innocence in the face of evidence that she was closely associated with Giacomo Medici for a number of acquisitions. Medici got ten years in the slammer and started an appeal. True — and Hecht — could get the same. Hecht wouldn’t have to serve time for, in Italy, seniors get no jail time.

By the time I was punching the keys for this chapter, the Getty finally saw the light. They followed the Metropolitan Museum and the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. The Metropolitan reluctantly made a deal to send fifteen grand objects back, including, as I’ve written, the Euphronios Sarpedon vase in exchange for lots of smiles, diplomatic sweet-talk and loans from Italy to the Met of things of equal value. Philippe de Montebello, who should be really proud of this landmark initiative which gives the Met a series of spectacular loans, was seen not too long after weeping into his cups and moaning that he’d be known “only for sending things back.” Correct, for every important Greek and Roman work but one acquired since 1966 has been returned. But he ought to be proud of this historic event nonetheless.

Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, pursued by the Italians, took a different course. Instead of stone-walling, delaying or tossing up a snowstorm of legal flummery, the director, Malcolm Rogers, swiftly returned thirteen disputed pieces to Italy including a blockbuster nine-foot marble portrait of Sabina, the wife of Emperor Hadrian. Rogers stated it was the “moral” thing to do.

The Getty sent back several items to Greece (for some reason the Greeks didn’t ask for the curious, spurious kouros). Greek prosecutors indicted Marion True anyway.

In late August 2007 the Getty agreed to hand back the big Aphro and forty of their most impressive smuggled antiquities to Italy. There will be years of exchanges of works equal in value and importance. The Getty Bronze was taken off the negotiating table, so that a special court in Pesaro can establish why the statue has no export papers from Italy.

As I have said, I have the sneaking suspicion that the bronze, too, will eventually return to Italy perhaps under the share deal I suggested.