Politics

Death Threats, Intimidation, Censorship: Inside the Far Right’s Assault on Brazil’s Art Scene

Artists and cultural professionals have been threatened and harassed by right-wing groups. Now, they must figure out what to do next.

Artists and cultural professionals have been threatened and harassed by right-wing groups. Now, they must figure out what to do next.

Henri Neuendorf

Last week, curator Gaudêncio Fidélis appeared before the senate in Brazil’s capital to face allegations of “mistreatment of children and teenagers.” His offense: Organizing “Queermuseum: Cartographies of Difference in Brazilian Art,” an exhibition of more than 200 works of Modern and contemporary art that explored queerness and gender at the Santander Cultural Center in Porto Alegre. The venue closed the exhibition a month early, on September 10, following violent protests and pressure from conservative political groups.

The furor surrounding the show is just one example of the mounting challenges to artistic freedom in Brazil, which hangs in the balance as right-wing groups work to shut down exhibitions and intimidate artists whose work they consider immoral. Dealers, curators, and artists say they have received death threats. And many are unsure of what to do in the face of a particularly 21st century kind of violence: One that begins online, but often has real-world consequences.

Indeed, some of the works cited by senators as offensive during Fidélis’s hearing were not even included in the original exhibition—they had been fabricated on social media by members of far-right political groups.

“There has been action to try and criminalize artists in Brazil, and politicians at lower levels of government are trying to take advantage of this because we are experiencing a very rampant and strong growth of fundamentalism,” Fidélis told artnet News. “There is this whole discussion around censorship… The right wing is pushing that agenda forward in a way that I’ve never seen before in art and culture.”

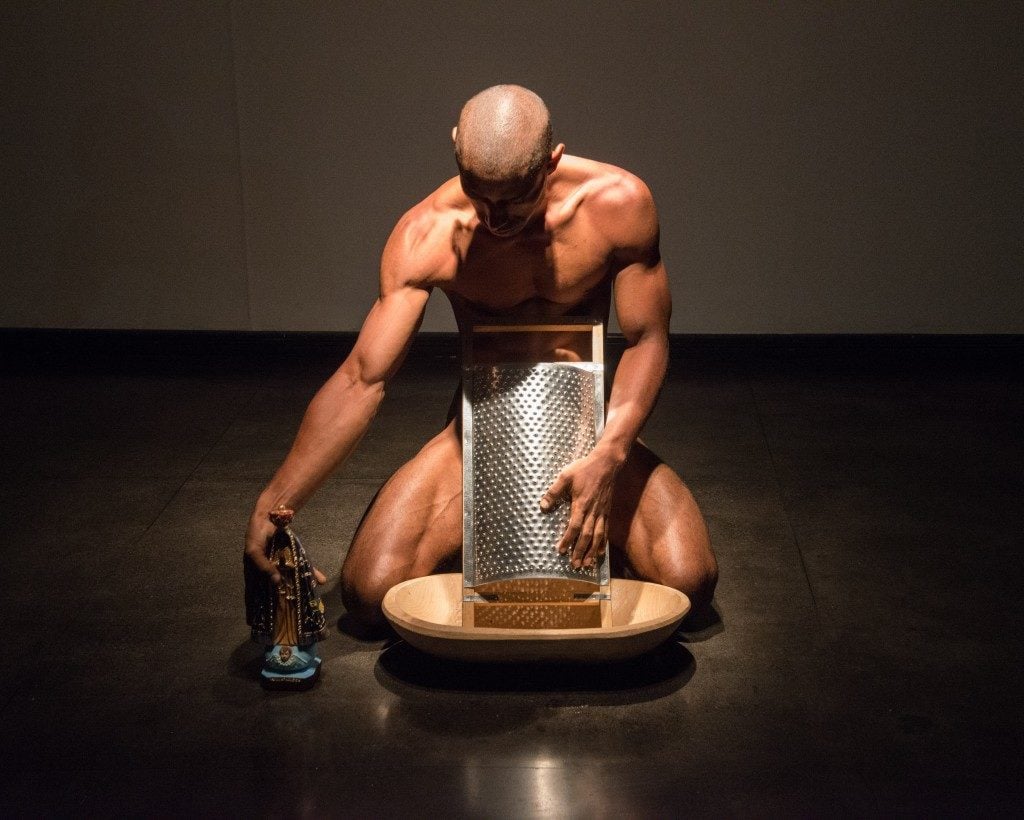

Antonio Oba’s Acts of Transfiguration: Disappearance of a recipe for a saint (2015). Photo: PIPA Art Prize.

The violence, or threat of violence, has forced some artists, like Antonio Oba, out of the country. After right-wing groups spread a video of one of his iconoclastic performances on social media, he received so many death threats that he fled Brazil. He has been living in self-imposed exile in Brussels since mid-October.

“With the increase of these threatening messages, I wasn’t able to produce work; anguish and insecurity overshadowed my practice, and hindered my work as a professor as well,” he told artnet News. “Considering all of these factors, I left Brazil for an artistic residency in Europe.”

In the offending video, “Acts of Transfiguration: Disappearance of a Recipe for a Saint” (2015), Oba grinds a white statuette of the Virgin Mary into a powder and pours it over his black body—an act, he says, of catharsis for the Catholic Church’s perpetuation of racism and intergenerational poverty. Soon after the video began circulating online, the evangelical right labeled it immoral and called for it to be banned.

Days later, on September 19, a group of right-wing activists were waiting with rocks outside an exhibition venue where Oba was due to install his work for an exhibition tied to the PIPA art prize (Brazil’s equivalent to the Turner Prize).

The last straw came when right-wing congressman Magno Malta threatened to sue Oba for blasphemy. He condemned the artist for “grinding the image of the saint and pouring the dust on his penis” and called him a “piece of shit” and a “son of a bitch” in a nationally televised senate hearing.

“That was the moment where [fellow gallery artist] Paulo Nazareth and a lot of other artists said, ‘Get him out of here,’” said the Brazilian dealer Pedro Mendes. His gallery, Mendes Wood DM, represents Oba and decided to fly him to Europe. “This can easily go wrong, if a legal case starts he could lose his passport,” Mendes explained.

The dealer noted that he received death threats himself after posting a video of one of Oba’s performances to Instagram. He is currently in New York, where the gallery operates a small space. Of the right-wing activists, he said: “They felt empowered, they felt if they continue this cyberterrorism, they could actually fuck up the structures of the liberal voice. And they can do it because the government is complicit.”

Brazilian president Michael Temer has been hostile towards the arts since he took power. Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images.

The recent incidents are part of a complex chain of events closely aligned with the populism and isolationism sweeping the globe.

Buoyed by press statements, social media campaigns, and street demonstrations, fringe groups such as the Movimento Brasil Livre (Free Brazil Movement or MBL) have gradually pushed Brazil toward the right of the political spectrum. They advocate hard line conservative agendas and position themselves against former president Dilma Rousseff’s neoliberal economic program and progressive social policies.

MBL’s rise was largely driven by divisive online vitriol against Rousseff, who was ousted by the conservative right in an impeachment vote in August 2016. Conservative rival Michael Temer, who replaced Rousseff, notoriously temporarily dissolved the country’s cultural ministry. (He ultimately reinstated it after sustained pressure from cultural groups and leftist activists, who occupied government buildings in protest.)

Ahead of Brazil’s general elections in 2018, politicians have sought to capitalize on the movement to the right by mimicking the divisive rhetoric of MBL in campaign speeches.

In this heated and divisive environment, the political vitriol has spilled over into Brazil’s left-leaning cultural arena. On November 7, American academics Judith Butler and Wendy Brown were intercepted by right-wing protesters at Congonhas Airport in São Paulo. The protesters later burned an effigy of Butler outside a conference venue, where they were giving a lecture on the history of sexuality.

“These attacks directed at art institutions and individuals are a way to change the debate into a moral issue to avoid talking about economic injustice, corruption, and civil rights that are being removed,” São Paulo-based artist Ana Prata told artnet News. “We had a coup last year, and in my opinion everything that is happening is a consequence of this.”

Ai Weiwei supports anti-censorship demonstrators in São Paulo. Photo: @victor_heringer via Twitter.

The first major uproar began in September, when conservative groups targeted an exhibition at the Santander Cultural Center in Porto Alegre. They alleged that the show, “Queer Museum: Cartographies of Difference in Brazilian Art,” promoted pedophilia and zoophilia. Protesters demonstrated in front of the museum and smashed windows of several branches of the Santander bank, which sponsors the venue.

At the start of October, images of a young girl—accompanied by a parent—touching the foot of a nude performance artist at São Paulo’s Modern Art Museum set off a firestorm of opposition. The performer had invited the audience to move his body as part of the performance, which was inspired by legendary Brazilian artist Lygia Clark’s interactive sculpture series Bichos.

Instead of condemning the attacks on freedom of speech and artistic expression, politicians including São Paulo’s mayor, João Doria (who is rumored to be lining up a bid for the presidency in next year’s election), went on the attack.

In a television address in mid-October, Doria criticized an exhibition on the history of sexuality at another museum, the Museu de Arte de São Paulo (MASP). Responding to public pressure, the museum restricted entrance to those over 18 years old. The move sparked counter-demonstrations by artists and cultural workers at the show’s opening. (The museum has now changed its policy to permit minors with adult chaperones.)

The Museo de Arte de Sao Paulo (MASP) museum in Sao Paulo has been the meeting point for counter demonstrations by artists and cultural workers. Photo: RENATO LUIZ FERREIRA/AFP/Getty Images.

In this politically charged environment, Brazil’s art scene is seeking strength in numbers, and some say the crisis has brought the community closer together. Fernanda Brenner, the artistic director of the São Paulo arts non-profit PIVO, is a driving force behind an open letter defending the right to artistic freedom in Brazil. The letter has garnered more than 1,000 signatures from leading Brazilian artists and cultural luminaries including Renata Lucas, Jac Leirner, and Nuno Ramos.

Like many others, Brenner feels the spate of recent incidents and the government’s refusal to condemn them amount to censorship. “I feel these recent attacks on freedom of speech, artists, and art institutions are an attempt to deviate attention from the atrocities this current government is trying to do in the National Congress,” she told artnet News.

But the Brazilian art world is not easily intimidated. Many of its members survived the country’s military dictatorship from 1964 to 1985, which also violently suppressed artistic freedom. Fernanda Feitosa, a collector and founding director of the São Paulo-based art fair SP-Arte, pointed out that while Brazil’s democracy has been bruised, its systems remain largely intact.

“I believe that Brazil has a solid legal system and the stability of cultural institutions in Brazil remains unshaken,” she said. “There are no signs yet that these minority groups are influencing the courts regarding legality or appropriateness of cultural exhibitions in the country.”

Fidélis, the Queermuseum curator, agrees, and is cautiously optimistic that the tide is slowly turning. “I think the strong reaction from the art world made people very conscious, and I feel like we’re somehow winning this fight,” he said. But, he warned, that the fight continues. “We cannot stop talking about this and fighting against these laws and against these initiatives that are very dangerous to democracy in Brazil.”