Politics

3 Ways Austria’s New Right-Wing Government Could Impact Its Art World (and Not All for the Worse)

Waves of anxiety are rippling through the Austrian arts community, and what the future may hold is anyone's guess.

Waves of anxiety are rippling through the Austrian arts community, and what the future may hold is anyone's guess.

Kate Brown

It’s only been a month since the new Austrian government came into power, but many in the arts community in Austria are already concerned about how the right-wing coalition might impact the country’s vibrant (and, at least for now, well-funded) arts and culture scene. Anxieties boiled over when, late last December, the country ushered in a new era as Sebastian Kurz from the center-right People’s Party became chancellor and opted to form his coalition government with the far-right Freedom Party, notoriously founded by ex-Nazi officials at the end of WWII.

There’s a worrying trend sweeping across several countries in Europe, with Hungary and Poland both under the sway of right-wing governments, and the anti-immigration party AfD in Germany achieving huge gains in the elections this past fall. (German Chancellor Angela Merkel has yet to put together her coalition government.) In Austria, the new chancellor is a 31-year-old wunderkind, the youngest leader in the world, and his recently sworn-in government has already released a program detailing some important changes to national policy. These include reduced assistance allotted to migrant workers, counter-reform to unemployment benefits for Austrians, and, most prominently, a revision of its immigration policy.

Earlier this month, thousands come out to protest in outrage when the new Interior Minister, Herbert Kickl of the Nazi-affiliated party, suggested asylum seekers should be “concentrated,” a word that struck many as all too evocative of Nazi-era concentration camps.

Things came to a head when the government released its new cultural program with the borrowed slogan from the Vienna Secession, the avant-garde artists’ association and exhibition hall that was founded in the late 19th century by Gustav Klimt and other important Austrian artists: “To every time its art. To art its freedom.” Immediately, the Secession hit back with a critical public statement, warning of the threat to the arts posed by a government that does not prize a free and open society.

Here are three things Austria’s shift in power could mean for the art world.

Detail of the Secession building in Vienna, with the movement’s motto emblazoned in golden letters on its facade. Photo: Wikimedia commons.

For now, changes in the nation’s arts and culture policy have not been clearly stated, but may be imminent. While the new Chancellor Kurz is pro-European Union (a plus, as many right-wing parties across Europe run on Brexit-type agendas), this allegiance with the far right is leaving many questioning the future of project spaces, nonprofits, and artists who rely partially or entirely on public funding from the Austrian government. In fact, in late December, several state-funded arts spaces and galleries received emails that their funding was put on hold. Commercial galleries, which receive financial assistance to cover the costs of attending international art fairs, are also concerned about their future.

“Bureaucracy seems to have come to a halt where funding is concerned,” according to Titania Seidl and Lukas Thaler, co-directors of the Vienna-based nonprofit MAUVE, which has been operating since 2012. “We haven’t heard from the largest funding body, the Federal Chancellery, since early December when we received a letter stating that we are eligible for funding, but they can’t give us an amount or indeed a date when they can tell us more about what’s going to happen.” They are still waiting, unsure how long they can keep up with their fixed costs and whether, as an arts initiative, they will be deemed valuable to this new government. “All we can do is wait and speculate,” they say.

Other nonprofits are also in limbo: Pina has had its funding frozen since December as well, Kevin Space is uncertain about its future, and many others are getting their applications rejected. “Artists and people who have been running projects that have existed for years through public funding alone have been telling me that their applications had been declined (in an unusually harsh way),” Pina co-founder Bruno Mokross told artnet News in an email, speculating that “cultural funding will most likely not be cut but redistributed to the countryside and towards more localist, nationalist, and traditionalist institutions and away from small-scale, subcultural projects.”

It’s not unusual during the handover of power for funding to be delayed due to re-evaluation, so many are adamant that there is no need to panic quite yet. But what has become clear at this point, as per the government’s new agenda, is that the promotion of artists will be awarded considering “clearly defined quality criteria.” The wording is vague, but one can infer what it may mean.

Quality also means a revaluation of art outside Vienna. “There will be a shift from the capital to the countryside and rural areas and that they want to move away from the so-called “Giesskannenprinzip”, which means smaller pots of budget for more initiatives to a more centralized funding, which means more money for less initiatives.” say Kevin Space, who fear this means a reduction in funding for alternative spaces.

The new government’s evaluation of quality will also lie in aesthetics. Take, for example the Freedom Party’s ongoing and vocal attack of the preeminent artist collective Gelatin.

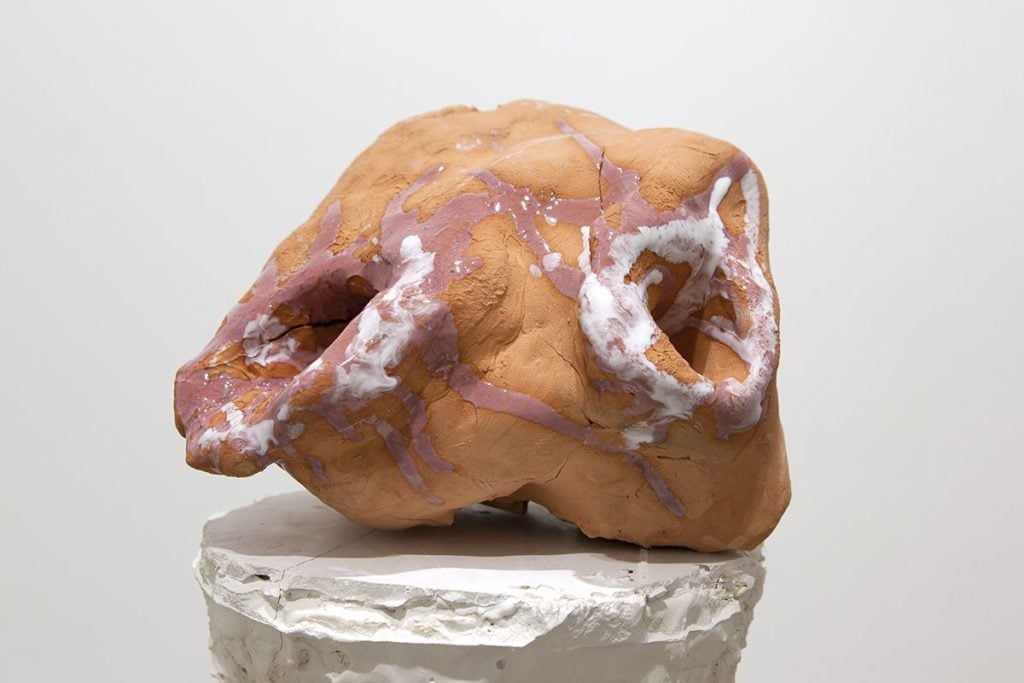

Journalist and Vienna-based arts writer Kimberly Bradley who has covered the Austrian arts and political scene for several years, told artnet News that the Freedom Party has long taken issue with Gelatin, and says she wonders if irreverent artists like that collective—which, in their a exhibition at Greene Naftali, had sex with clay sculptures—may see their support dry up or find themselves publicly condemned. In her recent article in Frieze exploring the projected cultural shift under this new government, Bradley predicts that though there likely won’t be strong censorship, there will be a “vilification of provocative aesthetics.” The last time the Freedom Party got into power with a similar coalition in 2000, it caused an exodus of Austrian artists to cities like Los Angeles and Berlin.

Freedom Party politician and Austrian Vice-Chancellor Heinz-Christian Strache tells two contemporary art viewers “You’re both thinking ‘this is real nonsense'” in the Freedom Party’s campaign video, titled “Let me say it for you.” Image via YouTube.

Installation view, “Gelatin: New York Golem” at Greene Naftali, 2017.

Many sources artnet News spoke to did seem to acknowledge how generous the funding system currently is. And the new minister of arts and culture, Gernot Blümel, is luckily, not from the more intolerant Freedom Party, and he has little arts or cultural experience—but that could be a good thing.

In a recent interview, Blümel was clear, saying that he “doesn’t want to make political statements with arts and culture, but rather make political agendas that support arts and culture.” artnet News reached out to the ministry of arts and culture with a request for comment, but did not receive an answer by the time of publishing. In any case, their more conservative-leaning economics will likely mean some trimming to funding, but there could be an unforeseen positive effect to the new government, at least in terms of activating the artist community.

“There might be a silver lining if there are cuts,” Bradley says. “Currently, if you have a project, you can propose a grant on three levels: municipal, regional, and federal, all three have culture budgets. Artists sometimes cobble together incredible grant packages for themselves. But in the end, nobody really oversees what happens to some projects. There might be a really great show that never travels, for example, or not enough viewers from outside coming to see an exhibition. A circular pattern emerges and you get artists that live off of grants and a few Austrian collectors, and there is not a lot of incentive to go further unless they are personally ambitious.”

“I’m not advocating for cuts,” she adds, “but maybe having a slightly more competitive system or results-focused accountability might do parts of the Austrian art world a lot of good.”

Arts spaces are already on the move, calling for solidarity in their community and getting more ambitious. Pina, for example, is working on its first fundraiser featuring Viennese artists to cover its costs, and the city’s independent art spaces are coming together to form a new regular round-table meeting to discuss and enact counter-measures to the (as yet speculative) changes in funding—but more importantly, to the turbulent political times ahead.