It’s hard to imagine, but there was a time when airplanes were a novelty. They heralded technological progress, sparked skyward wonder, and offered a whole other dimension to travel, one realized by the commercial flight boom in the 1950s. Artists took to the skies, in every sense of the phrase. Many were enamored by the views afforded by flight; others were drawn in by what aviation meant for an innovative new age (looking at you, Futurists). Below, meet seven artists who took their fascination with flying to the canvas.

Georgia O’Keeffe

Sky Above Clouds IV (1965)

Georgia O’Keeffe, Sky Above Clouds IV (1965).

O’Keeffe’s expansive feelings about flying are barely contained in this massive, eight-by-24-feet canvas. While jetting around the world in the 1950s, the artist often sketched on airplanes, attempting to capture the view of the landscape from the sky. “Such things as I have seen out this window I have never dreamed,” she once wrote to her sister Anita on a flight from Tehran, describing such sights as green river systems and sharp mountains. This painting joins her other abstract aerial views such as Green, Yellow and Orange (1960) and Drawing I (1959), in which her visual language takes flight.

Kazimir Malevich

Suprematist Composition: Airplane Flying (1915)

Kazimir Malevich, Suprematist Composition: Airplane Flying (1915). Found in the collection of © Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images.

Cue the Futurists! Or in Malevich’s case, a Suprematicist who rejected realism in favor of pure geometric abstraction. His painting of a flying airplane, then, does not depict an actual aircraft, but illustrates the experience of flight—the spatial relationship of rectangles conveying motion and the colors indicating an upward trajectory. So dedicated was the Russian artist to this mode of painting that he believed it would outstrip both Cubism and Futurism in a brave new world of dynamic movement. “Can a man who always goes about in a cabriolet,” he wrote, “really understand the experiences and impressions of one who travels in an express or flies through the air?”

Alexander Calder

.125 (1957)

Jamaica, N.Y.: Port Authority executives Austin J. Tobin (executive director) and John Wiley (director of aviation) in the main lobby of Idlewild Airport (now John F. Kennedy International Airport), installed with Alexander Calder’s mobile, 1957. Photo: Bill Sullivan/Newsday RM via Getty Images.

Okay, Calder’s monumental mobile installed at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York may or may not have anything to do with flight. But was it not designed for a space where airplanes land and take off? Which makes sense for an artist, once trained as an engineer, who was preoccupied with building movement into his sculptures. “Just as one can compose colors or forms, so one can compose motions,” he once wrote in a statement that further alluded to Futurism. Later, in 1973, Calder worked with Braniff Airways to paint a series of jets in his multihued designs, sending his art, finally and quite literally, into the skies.

Natalia Goncharova

Airplane Over Train (1913)

Natalia Goncharova, Airplane Over Train (1913). Photo: Public Domain.

The Russian avant-garde artist, in embracing her native land as a creative source, captured rural cultures in her idyllic early 1900s canvases. But her alliance with Futurism meant she was also captivated with the ways technology was encroaching on Moscow society. Hence her works depicting looms, cyclists, and airplanes, drawn with a Cubist fragmentation and capturing how “the mechanized and the bio-mechanical are one and the same.” In this 1913 canvas, though, only the slightest shadow of a human form is visible amid the vehicles’ angular parts, as if seen from some distance—or height.

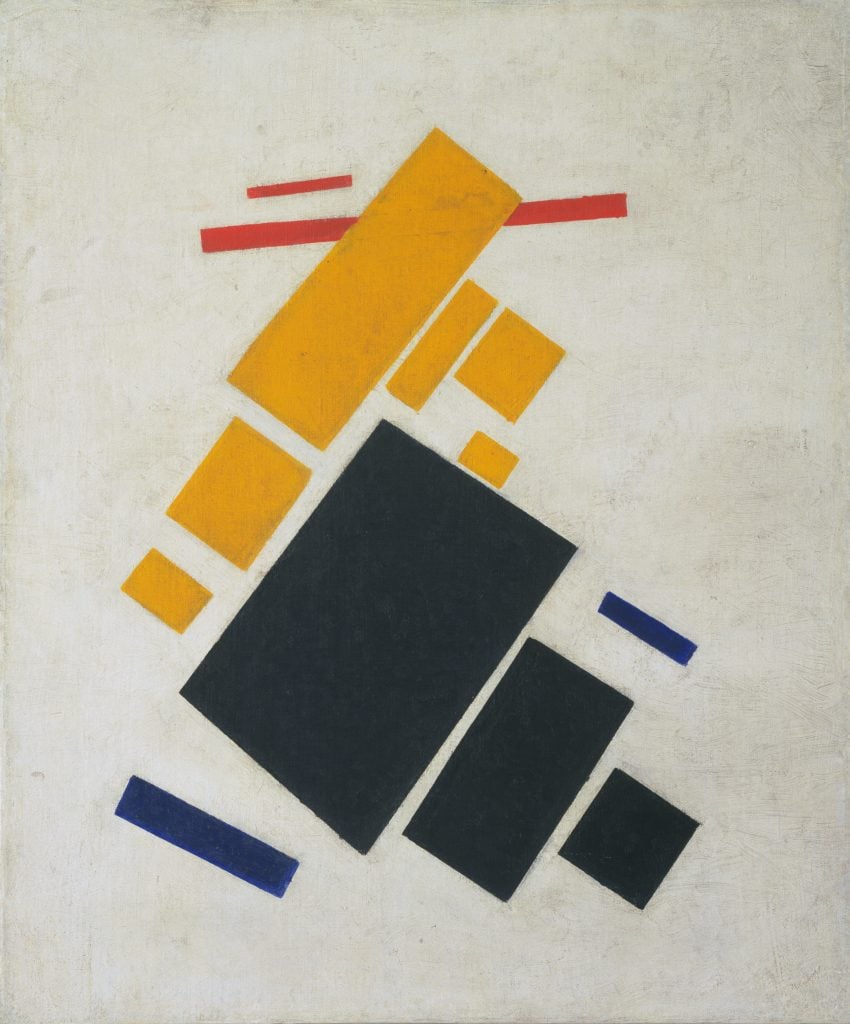

Le Corbusier

Urban plan for Rio de Janeiro (1929)

Le Corbusier’s urban plan for Rio de Janeiro, from The Radiant City: Elements of a Doctrine of Urbanism to be Used as the Basis of Our Machine-Age Civilization (1967).

The Swiss architect’s embrace of the aircraft was such that he wrote an entire book on the subject in 1935, lauding the “modern conscience” and “eagle eye” aviation offered. It was this aerial view that inspired Le Corbusier’s urban plan for Rio de Janeiro. He had purportedly sketched the proposed elevated city while on an airplane, “just when the conception of a vast program of organic town-planning came like a revelation,” he wrote. Alas, his eagle-eyed theories of urban design, dubbed his Radiant City, would prove insensitive to everyday cultures and lived experiences, which require perspectives far more down-to-earth.

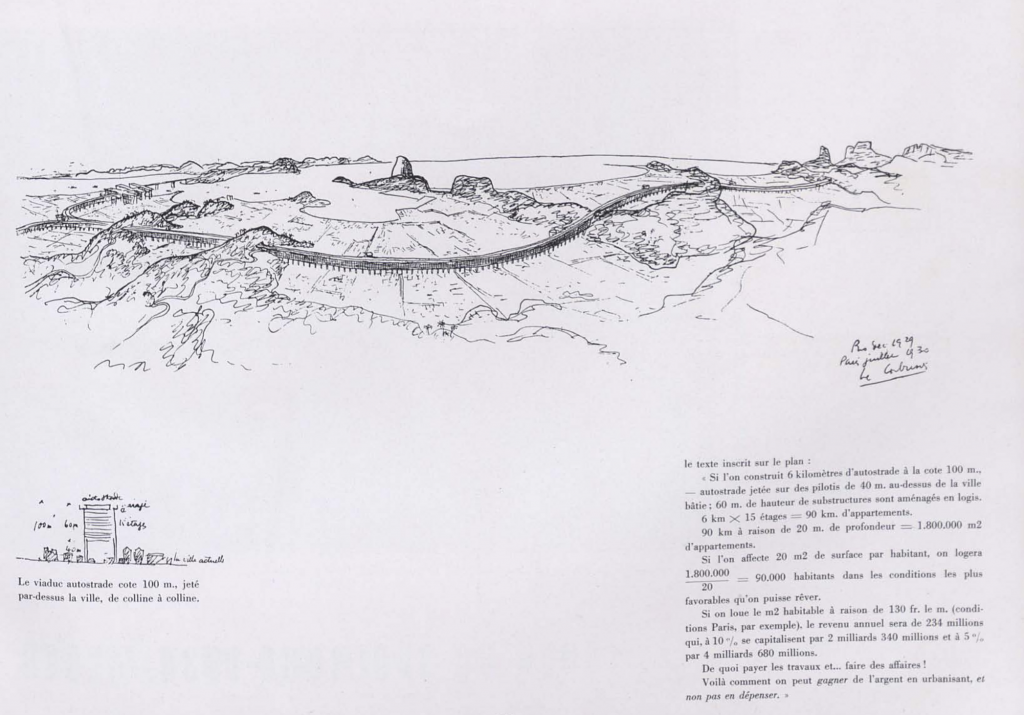

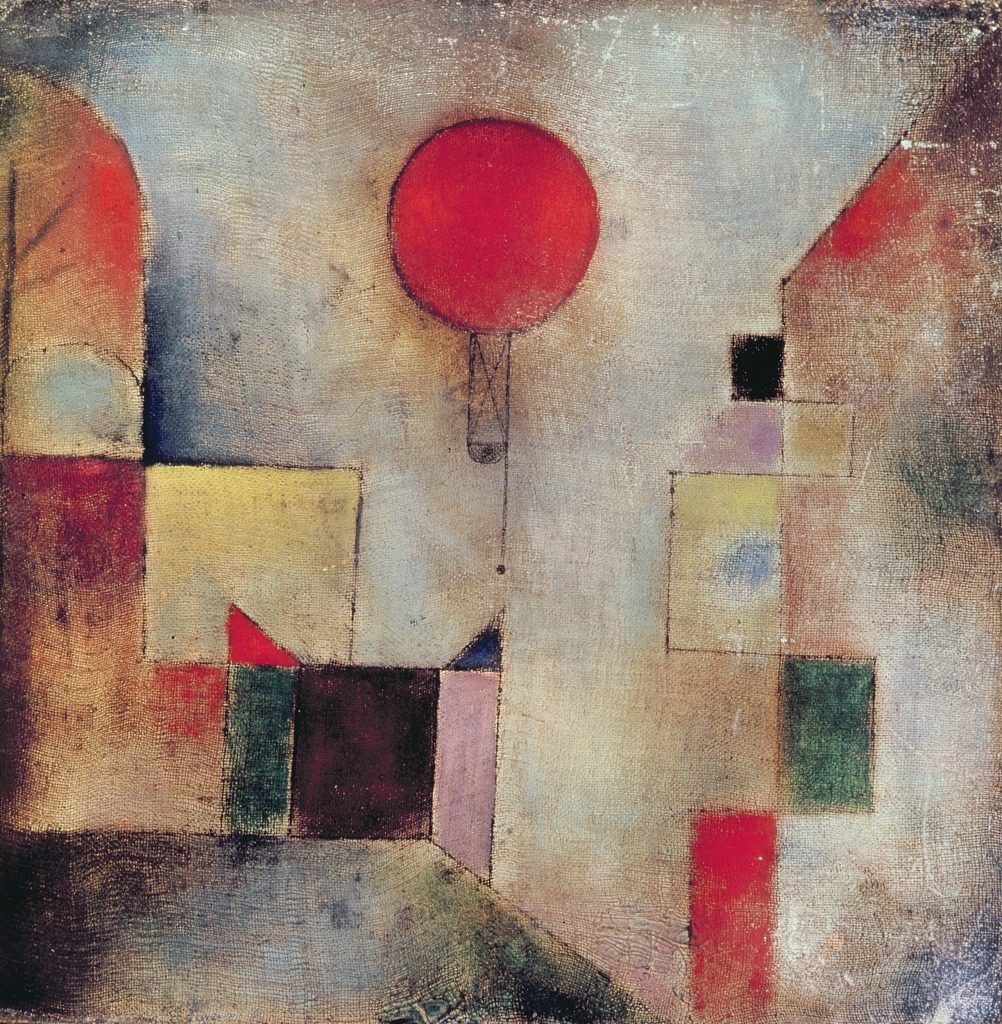

Paul Klee

Red Balloon (1922)

Paul Klee, Red Balloon (1922). Photo: Art Images via Getty Images.

Typical of Klee’s whimsy, his ode to air transport harks back to an earlier age of aviation, rendering a striking hot-air balloon floating above a geometric cityscape. Flight, however subtly, was a running theme in the artist’s expressive body of paintings, which variously referenced birds, angels, and in 1917’s In the Realm of Air, even more balloons. During World War I, Klee was conscripted into the German army where he was put to work restoring aircraft camouflage—an experience that would inspire his motif of arrows (as symbols for weapons or downed planes) as well as his use of airplane linen as a canvas.

Robert Delaunay

Homage to Blériot (1914)

Robert Delaunay, Homage to Blériot (1914). Photo: Sepia Times/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

Pioneering aviator Louis Blériot made the first airplane flight across the English Channel in 1909, clinching a cash prize of £1,000 and Delaunay’s esteem. If this joyous composition of disks, backgrounded by a biplane and the Eiffel Tower, doesn’t capture the French painter’s awe at Blériot’s heaven-bound technology, then maybe his rapturous description of the work will. “Constructive mobility of the solar spectrum; dawn, fire, evolution of airplanes,” he reflected. “Everything is roundness, sun, earth, horizons, intense plenitude of life, a poetry which one cannot render into language.”