Politics

Artist Candice Breitz Has Found a Creative Way to Protest a Museum’s Link to Refugee Prison Camps

The artwork is due to go on view this week at the National Gallery of Victoria Triennial.

The artwork is due to go on view this week at the National Gallery of Victoria Triennial.

Sarah Cascone

When South African artist Candice Breitz‘s work Love Story goes on view at the National Gallery of Victoria this week, it will have a new name: Wilson Must Go.

Breitz is rechristening the seven-channel video piece—which features actors Alec Baldwin and Julianne Moore recounting the tales of refugees in first person—in protest of the NGV’s current use of the firm Wilson Security, a company that oversaw the imprisonment of thousands of immigrants and refugees to Australia on Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island and the island nation of Nauru.

The piece—which channels the power of celebrity to bring attention to the plight of refugees—has now become a work of protest against the mistreatment of immigrants at Australia’s offshore detention centers.

The video installation is set to go on view December 15 in the NGV Triennial (through April 15), a sprawling exhibition featuring work by 100 artists and designers including Camille Henrot, Yayoi Kusama, and Teamlab. Breitz’s work, Love Story, was commissioned by the NGV and previously on view in the South African pavilion at the 2017 Venice Biennale. It will next appear at South Africa’s Goodman Gallery (Feburary 1–March 10, 2018) and at Cleveland’s FRONT Triennial in July.

In this handout photo provided by the Australian Department of Immigration and Citizenship, facilities at the Manus Island Regional Processing Facility, used for the detention of asylum seekers that arrive by boat, are seen on Manus Island, Papua New Guinea in 2012. Photo courtesy of the Australian Department of Immigration and Citizenship via Getty Images.

“The new title will remain in effect for as long as the work is on view at the National Gallery of Victoria, or when the work is exhibited in any other exhibition context on Australian soil, until the NGV severs its relationship with Wilson Security,” Breitz wrote on Facebook. She encouraged other participating artists to follow her lead and similarly rename their works “Wilson Must Go.”

The museum has said its use of Wilson is temporary. Neither the security company nor the museum immediately responded to artnet News’s request for comment.

In 2015, an Australian Senate report found that there had been 30 allegations of child abuse and 15 reports of sexual assault or rape at the detention facilities overseen by Wilson, according to the Sydney Morning Herald. The Papua New Guinea Supreme Court ruled in April of 2016 that the Manus Island detention center was illegal.

In this handout photo provided by the Australian Department of Immigration, the Nauru Island detention camp for immigrants to Australia was damaged by a 2013 riot. Photo courtesy of the Department of Immigration via Getty Images.

The company began work at the detention centers as a subcontractor for Transfield Services, a government contractor, in 2012. In 2014, a number of artists protested the Biennale of Sydney for being sponsored by Transfield’s parent company, Transfield Holdings.

Their threats to boycott the exhibition led the Biennial to drop to Transfield as a sponsor. In an effort to distance itself from the controversy, Transfield Holdings rebranded Transfield Services as Broadspectrum in 2015, and sold the company to Spanish infrastructure giant Ferrovial.

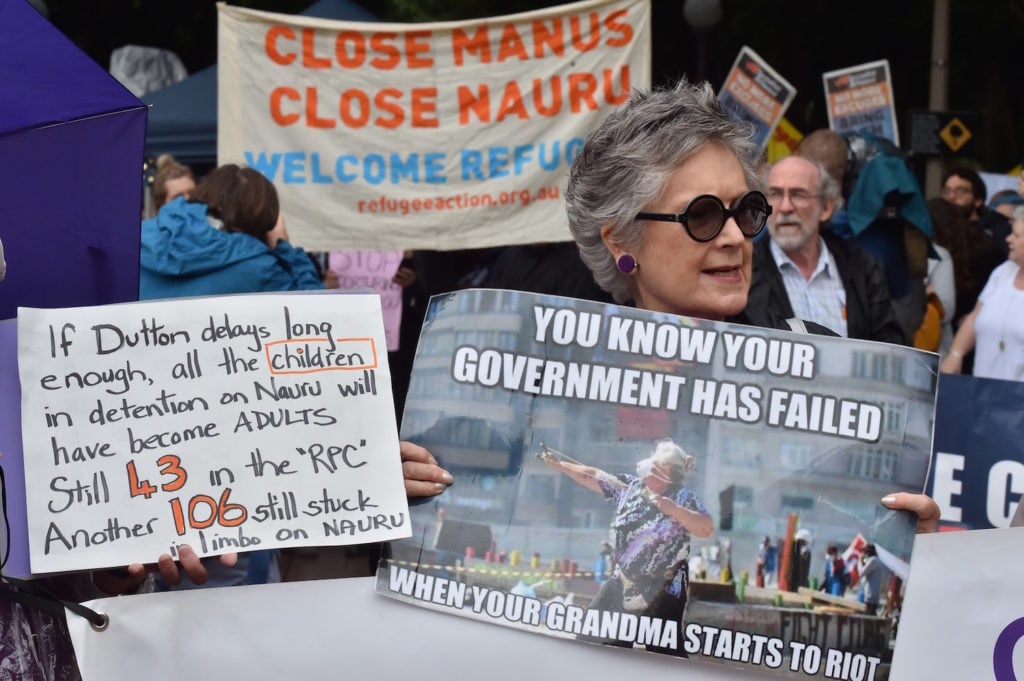

Protesters hold a rally in Sydney to urge the Australian government to end the refugee crisis on Manus Island on November 4, 2017. Photo courtesy of Peter Parks/AFP/Getty Images.

The contracts for Broadspectrum and Wilson were set to expire near the end of October, and both companies opted to cease their work at the facilities. The government shut down the Manus Island camp at the end of October—a chaotic process. Under a deal brokered by President Barack Obama (to his successor’s displeasure), some refugees from the centers have resettled in the US, with more expected to follow.

But regardless of the current status of the center, Wilson’s long-term involvement there remains a fact.

Julianne Moore and Alec Baldwin in Candice Breitz’s Love Story, a pro-refugee video work now retitled WILSON MUST GO in protest of the National Gallery of Victoria’s use of Wilson Security, which ran Australia’s controversial offshore immigration detention centers. Video still courtesy of the artist.

Breitz’s decision to rename her work poses an interesting alternative to boycotting or pulling a work from a show in protest of a sponsor or contractor.

“I trust,” Breitz wrote, “that the NGV will receive this gesture as one of solidarity, solidarity with the Triennial’s focus on forced displacement, but more importantly, solidarity with all refugees and asylum seekers who have been or remain subject to the cruelty of the Australian offshore detention regime, as enforced by agents like Wilson Security.”

Read Breitz’s statement in full below.

>> WHY I’M SABOTAGING MY OWN WORK <<

+++++++ WILSON MUST GO ++++++++++++

I am one of many artists participating in the National Gallery of Victoria’s inaugural NGV Triennial, an exhibition that is scheduled to open in Melbourne this week. ‘Movement’ is one of five themes that frame the Triennial. Consequently, the exhibition includes a number of works that engage with and represent the global crisis of displacement. My own work, LOVE STORY, a video installation that evolves out of interviews with six individuals who have fled their countries in response to a variety of oppressive conditions, has been enabled and acquired by the NGV for the Triennial, via a generous artist commission.

It has come to my attention, via the Artists’ Committee (an informal association of Melbourne-based artists and arts workers), that security services at the NGV are currently provided by a private security contractor called Wilson Security. On their website, Wilson claims to ‘offer the highest level of protection and peace of mind for [their] customers across myriad industries and complex business scenarios.’ Under contract to the Australian government, however, Wilson security has violently enforced the imprisonment of refugees and people seeking asylum in Australia’s offshore immigration detention centres. The horrific effects of indefinite mandatory detention are well-documented. The allegations against Wilson Security since the commencement of their contracts on Manus Island and Nauru in 2012 are extensive and disturbing. While I am grateful for the immense support I have received from the NGV, it would be morally remiss, in light of the above knowledge, for me to remain silent in the context of the current conversation that is taking place around the Australian government’s ongoing and systematic abuse of refugees.

I have been assured by the NGV that the contractual relationship between the gallery and Wilson Security is of a temporary nature. I have been told that the tendering process that will culminate in the appointment of a more permanent contractor is at an advanced stage. As such, the response that this statement articulates is itself potentially of a temporary nature:

With immediate effect, the work of art that was formerly known as LOVE STORY will carry the new title WILSON MUST GO. The new title will remain in effect for as long as the work is on view at the National Gallery of Victoria, or when the work is exhibited in any other exhibition context on Australian soil, until the NGV severs its relationship with Wilson Security. Until that point, the work will continue to speak its objection to being under the surveillance of a security contractor that commits human rights abuses in Australia’s offshore detention centres. Until that point, all NGV publications of any nature, all public discussions hosted by the NGV, any educational conversations conducted around the work at the NGV, any and all press communications issued by the gallery, and all wall texts and captions, shall refer to the work as WILSON MUST GO. The title of the work will automatically revert to LOVE STORY if and when Wilson goes. Should they wish to, I invite other Triennial artists who may share my discomfort at having their works under the surveillance of Wilson Security, to temporarily rename their own works WILSON MUST GO.

It is extremely unfortunate that individual security workers who are currently engaged at the NGV may experience negative repercussions as a result of this intervention. The NGV has assured me that fair treatment of their security staff is of high priority. I have every reason to believe that the NGV will provide secure working conditions for their security staff, and wish to make clear that this intervention in no way wishes to target specific individuals who currently provide security services on NGV premises.

The moral failure characterising the Australian government’s refugee policy is all the more deplorable in ‘a nation that has been forged through stories of mobility.’ As the NGV Triennial catalogue states, ‘The challenge of hospitality is not an abstract philosophical problem or a minor political issue.’ I have experienced my interlocutors at the NGV to be deeply attuned to the horrific conditions and challenges facing refugees and asylum seekers worldwide. I trust that the NGV will receive this gesture as one of solidarity, solidarity with the Triennial’s focus on forced displacement, but more importantly, solidarity with all refugees and asylum seekers who have been or remain subject to the cruelty of the Australian offshore detention regime, as enforced by agents like Wilson Security.

Candice Breitz

Melbourne, 12 December 2017