Art Criticism

American Titan Bruce Nauman Burns Bright in a Poignant New Show

Artist-poet William Blake makes an appearance in the exhibition's centerpiece work.

At 83, Bruce Nauman can still surprise us. “Bruce Nauman: Begin Again,” his 15th solo show at the Sperone Westwater gallery in New York, shows one of the premier artists of our time exploring new formal and emotional territory, albeit in works with a great deal of similarity to earlier ones.

The visitor is greeted, if that’s the word, by a forest of 17 hanging sculptures in the shape of animals, plaster casts of taxidermy forms. Dangling by wires in the high-ceilinged gallery are foxes and coyotes, either solo or bound together in various groupings. That same wire also binds them roughly, rudely, together, along with assorted other stuff—a metal plate here, a cardboard box there. Nauman has plumbed these animal forms since he first came across them in a New Mexico taxidermy shop, in 1988, but in this installation, they crowd menacingly around you.

Bruce Nauman’s studio. Courtesy Sperone Westwater.

Tools, mostly hammers and ax handles, are integrated into the sculptures, anchoring some of them to the floor. Another familiar sight from earlier in Nauman’s career are a pair of bronze heads that rest on the floor in one of the sculptures, ominously close to some of those hammers. The animal casts suggest the kind of unsentimental relationship that a man who lives on a rural New Mexico ranch, as Nauman does, might have with wild creatures, but their frozen contortions—twisting through the air, some with their heads on backwards—evoke pain.

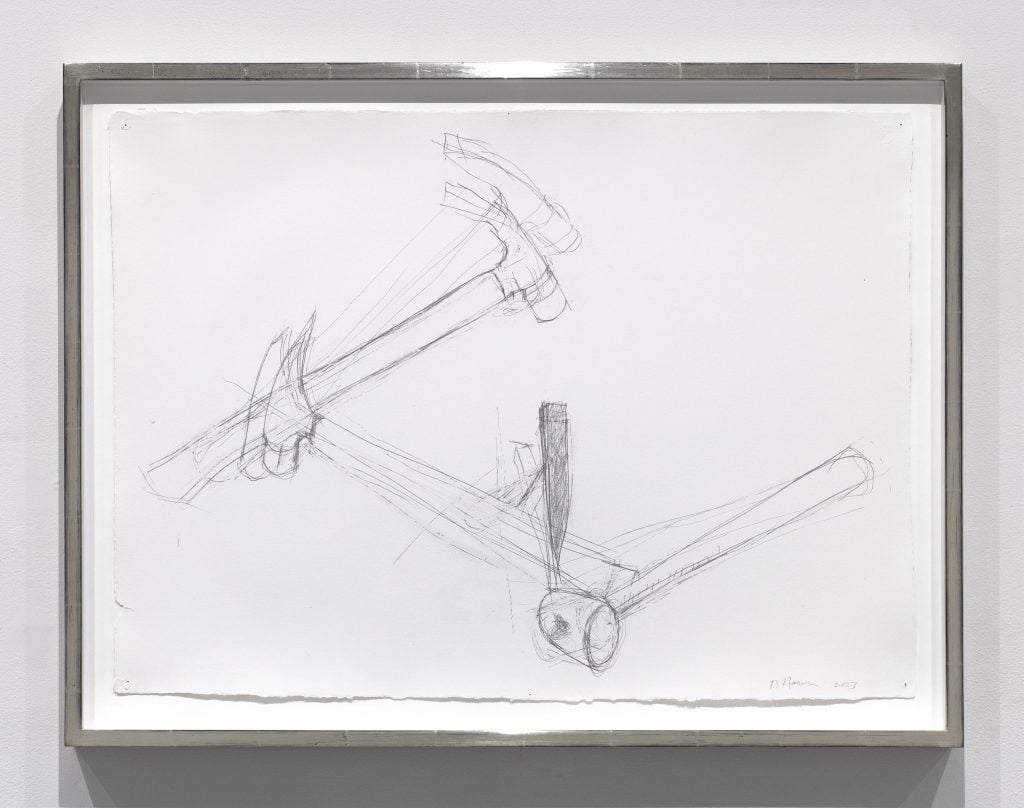

In numerous silverpoint and goldpoint drawings, Nauman renders the new sculptures, their component parts, and views of his studio. “I really like to draw, and I was pretty good at it at one point,” Nauman said in press materials. (He rarely submits to interviews.) “I drew for two reasons: when I was making sculpture and installations, I drew to figure out how to go about the work and what it might be, and then I drew the finished work to help me understand what I’d made. Drawing was about the sculpture, and these drawings are, too.”

Bruce Nauman, Hammers (2023). Courtesy Sperone Westwater.

Also set in the studio, and exhibited near the thicket of hanging sculptures, is a 3D video, Untitled (Turning, Swinging and Striking) Dedicated to Bruce Hamilton and Susanna Carlisle (2024), named for the artist-collaborators who devised a method of using two iPhones to create stereoscopic video. In it, we assume the place of the artist as he navigates those same animal-cast sculptures in the famously messy surrounds of his workspace.

The two-minute video is most notable for the gentle chiming that results when Nauman bumps the hammers into the bronze heads, delivering the blow threatened by his sculptural installation. The artist said in a 1988 Art in America interview that he aspired to create art that would hit you like a baseball bat to the back of the neck. The delicate impacts he delivers here suggest that he is now after something far more subtle.

The show’s centerpiece is another video, Walk with Tyger (2024), which shows the artist wearing jeans and a T-shirt as he paces back and forth in his studio, arms stretched out to from sides, sometimes unsteady on his bare feet. Nauman followers will be accustomed to this image, too, as it goes back to his earliest days. In his very first studio after art school, he found himself at a loss for how to proceed; when he finally decided that whatever an artist did in his studio was, by definition, art, he created now-canonical videos there in which he put himself through various paces.

Bruce Nauman, Walk With Tiger (2024). Courtesy Sperone Westwater.

Videos of him walking—striking a contrapposto pose, for example—have become a staple of his practice. In his videos, he has also put the image of his body through all sorts of iterations, multiplying it, cutting it apart, showing it in 3D, and so forth. In Walk with Tyger, its upper and lower halves are severed, so that their moves are not synchronous. His legs, for instance, sometimes face away even as his torso faces us. The splicing suggests alienation from one’s own mortal coil. In fact, following chemotherapy treatments to treat bowel cancer, the artist temporarily lost feeling in his legs and feet, compromising his ability to walk.

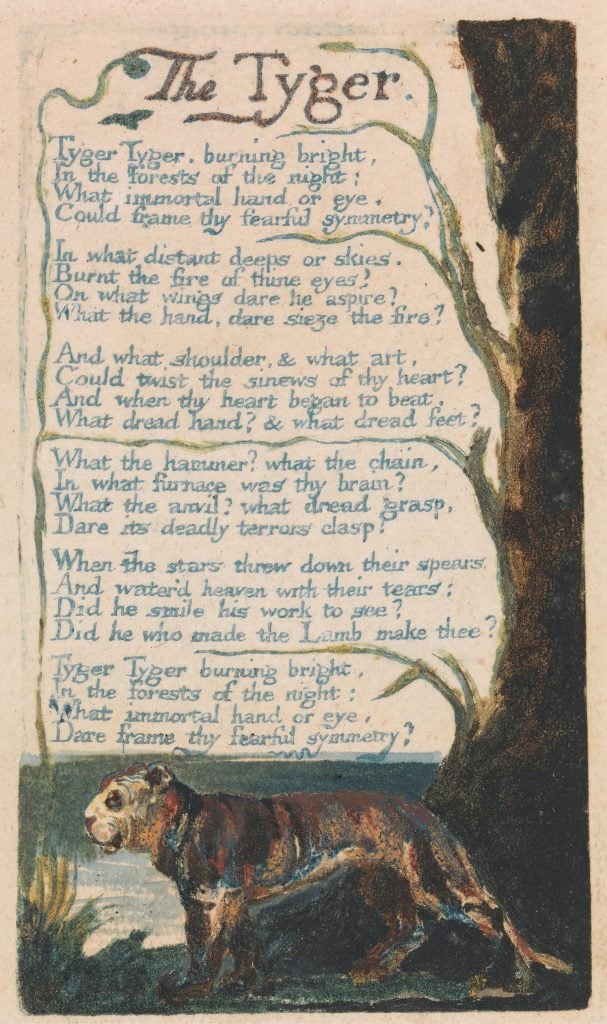

Though fans will recognize much in the 15-minute video, it includes a crucial new feature: The soundtrack has the artist’s raspy voice giving a restrained reading a William Blake’s classic, “The Tyger,” published in the artist-poet’s 1794 collection Songs of Experience. In it, the poet asks the fearsome beast who might have created it: “Tyger Tyger, burning bright, / In the forests of the night; / What immortal hand or eye, / Could frame thy fearful symmetry?”

William Blake, Songs of Innocence and of Experience, Plate 42, The Tyger. Getty Images.

The widely anthologized poem is a pendant to “The Lamb,” from the poet’s Songs of Innocence (1789), in which the narrator asks the subject, “Who made thee?”, finally informing the creature that it was crafted by the lamb known as Jesus Christ. In “Tyger,” Blake asks, regarding the beast’s maker, “Did he smile his work to see? / Did he who made the Lamb make thee?”

It all adds up to a remarkable sight. As we regard Nauman’s aging body, we listen to him asking questions about the nature of the creator. A tiger of an artist, who has for decades unsparingly explored human existence in all its ugliness and glory, muses on who made him.

A few drawings point in a different direction, and I can’t help but link them together in my thinking about the show. One, in the artist’s unmistakable slanted, all-caps hand, reads, “standing in the crossroads heart in hands,” words from a song by bluesman Elmore James, whose narrator laments mistreatment by his absent lover, concluding, “She’s out with another man.”

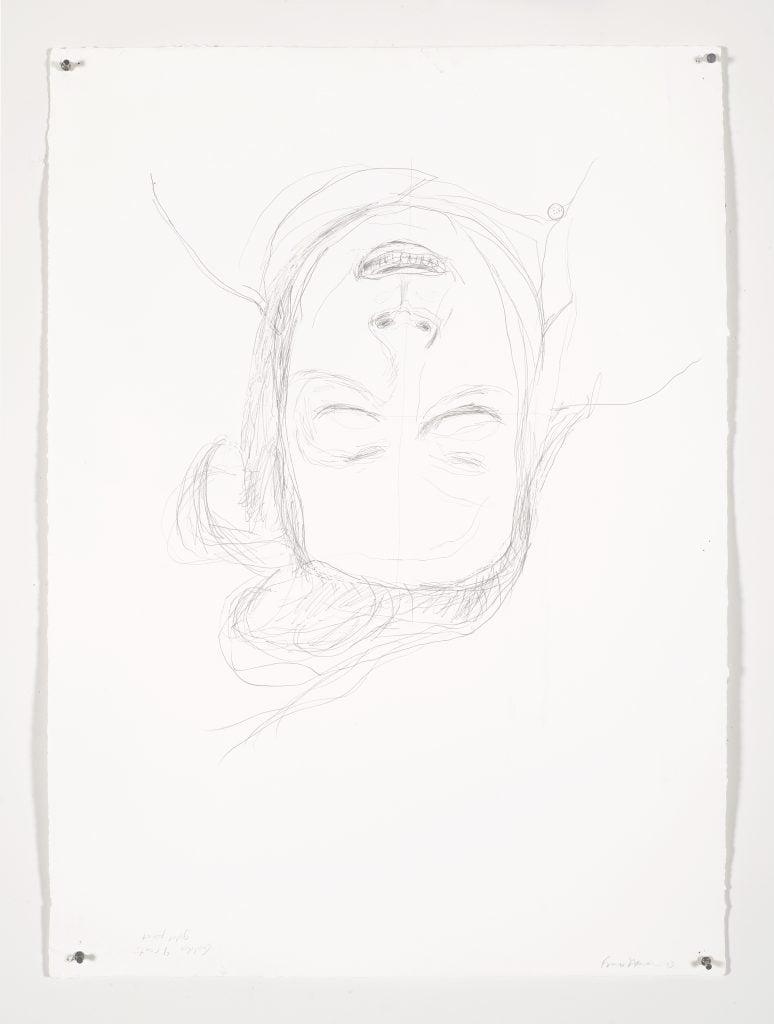

Bruce Nauman, Untitled (2023). Courtesy Sperone Westwater.

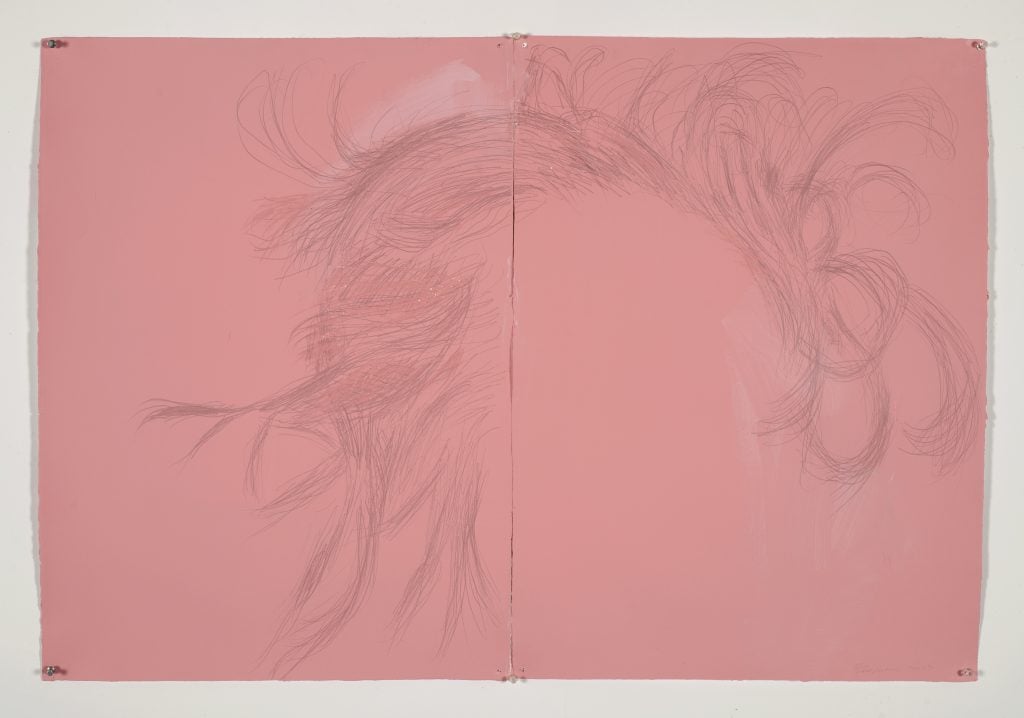

Meanwhile, several spare drawings show a human figure, a rarity in the artist’s drawn work. Two render a face with eyes closed, teeth visible in what seems a lightly fixed grimace. Others mysteriously render only the hair surrounding an absent visage, each stroke seeming to replicate a strand.

Bruce Nauman, Untitled (2023). Courtesy Sperone Westwater.

My jaw dropped when I learned that these are postmortem renditions of his late wife, the groundbreaking artist Susan Rothenberg, whose 1970s paintings of horses lit a pathway out of Minimalism and abstraction. (Horses became a frequent presence in Nauman’s later work and in his other professional life, in which for a period he broke and sold the animals.) Nauman and Rothenberg married in 1989; she died in 2020. Tenderness and sadness are imbued in every strand of hair in these drawings, by an artist gazing, unflinching, at mortality (those teeth!). The drawing with the Leonard lines is subtitled “bad week.”

Considering that “heart in hands” drawing, I find myself thinking that Nauman’s departed wife has gone off, after a fashion, with another man. Is he the one who made the lamb? The one who made the tiger? Will he one day come for us, too?

“Bruce Nauman: Begin Again” is on view at Sperone Westwater, 257 Bowery, New York, through January 18, 2015.