Have you ever wondered what your rights are as an artist? There’s no clear-cut textbook to consult—but we’re here to help. Katarina Feder, a vice president at Artists Rights Society, is answering questions of all sorts about what kind of control artists have—and don’t have—over their work.

Do you have a query of your own? Email [email protected] and it may get answered in an upcoming article.

The US presidential campaign is in its final stretch, and you know what that means: famous musicians are suing politicians to stop them from using their songs on the campaign trail. I’ve always wondered, why are they allowed to do that? Why can’t politicians use whatever music they want?

You’re right to be a little confused. A solid copyright infringement case must demonstrate that the artist has lost business as a result of the unauthorized use. But candidates running for office aren’t supposed to be making money off of the process—so why should the musicians care?

The “why” becomes clearer when you consider the identities of the aggrieved parties and the defendants: George W. Bush was sent a cease and desist by Tom Petty, Jackson Browne sued John McCain, David Bryne and the Talking Heads sued former Florida governor Charlie Christ. And, of course, who could forget about the time that the guys who did Eye of the Tiger sued Newt Gingrich? Chalk it up to differences of opinion in our wonderful American marketplace of ideas.

President Donald Trump speaks at a rally a day after he formally accepted his party’s nomination at the Republican National Convention on August 28, 2020. (Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images)

The “how” is an issue close to my heart, because it involves collective rights organizations that are much like mine, Artist Rights Society. Three music-industry groups known as “Performance Rights Organizations” (PROs) control the rights for most music in the United States: the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP); Broadcast Music, Inc (BMI); and SESAC Holdings, Inc.

These groups have strong relationships with musicians and frequently employ blanket agreements with venues like concert halls and convention centers—but the agreements tend to exclude political rallies, which require their own individual licenses.

In short, musicians have a wide variety of ways to get politicians in trouble for playing their music at rallies without permission. And since this is pretty much the only thing politicians actually get in trouble for these days, I think that’s beautiful.

Being quarantined in our 500-square-foot apartment has convinced my partner and I that we can survive anything, so we’ve decided to get married. She wants to do a prenup, and as an artist, I’m inclined to put something in there about the rights to my artwork. Do I need to be worried about those in the event of a divorce?

Congratulations! Both on the marriage and on taking the responsible step of getting a prenuptial agreement. Here at ARS, we believe that the only thing more sacred than the bond between a married couple is the one that exists between an artist and their intellectual property.

Unlike in marriage, there isn’t a lot of paperwork involved with copyright: it’s granted automatically to an artist following the creation of an artwork and basically exists in the ether (until you want to sue an illicit user for copyright infringement—that requires paperwork).

Still, divorce lawyers have proven as adept at dissecting the ether as they are at dividing assets. Take, for example, Da Vinci Code author Dan Brown, whose ex-wife is seeking what she believes is her share of the author’s recently released classical music album for children (he composed the songs some 30 years ago, before he was married). Or consider “Peanuts” creator Charles M. Schultz, who ended up giving his first wife a whopping 27 percent of the business after their 1973 split.

“Peanuts” creator Charles Schulz. Photograph by Roger Higgins. Courtesy of Wikimedia.

On a federal level, copyright belongs only to the artist or creator, but things become complicated in US states, like California, with community property laws. In such states, most judges base their answer to the copyright question on an appeal filed in 1987 regarding the California divorce of Susan and Frederick Worth. They had divorced five years earlier, not long after Frederick published two books on trivia for which the pair agreed to share royalties. In 1984, however, Frederick sued the makers of “Trivial Pursuit,” alleging that they had stolen questions from his book. Susan asked the court for half of anything that Frederick won.

Frederick lost the case (despite the fact that he made up one of the allegedly appropriated pieces of trivia precisely to protect against this kind of theft: Columbo’s first name was never actually revealed on the show). But in that 1987 appeal of her own separate case, the court was clear: Susan did indeed have claim to his copyright.

According to the court, it doesn’t matter that Frederick alone penned the trivia books. “The principles of community property law do not require joint or qualitatively equal spousal efforts or contributions in acquiring the property,” the ruling stated. All that matters is that the spouse expended that effort during the marriage.

This Worth case guided the 1992 divorce of George G. Rodridge, an artist from Louisiana, which is another community property state. In other words, depending on where you get married or divorced, anything you create during holy matrimony might be up for grabs, copyright-wise. So unless you’re comfortable with that, you’d better say otherwise in the prenup.

I’m a medical illustrator. A pair of lungs I drew in the early 2000s has somehow made its way onto a popular Facebook post that calls COVID-19 a hoax. I’m more outraged about the context than the appropriation. What recourse do I have?

Rest assured: the lungs you drew are, in the eyes of the law, just as protected as Picasso’s take on the violin.

The person who posted your illustration likely isn’t making any money off of it, so a lawsuit might be more trouble than it’s worth. But while Facebook may be, by its own admission, completely untrustworthy when it comes to facts, they’re actually just as effective at addressing potential copyright infringement as they are at radicalizing your aunt.

If anything, they’re overzealous. When the pandemic started, the Santa Barbara classical music trio Camerata Pacifica were told that they couldn’t post videos of their past performances because Facebook’s bots found they had violated Mozart’s copyright. (Just a reminder: copyright lasts for the creator’s lifetime plus an additional 70 years, and Mozart died in 1791).

Your best bet, then, is to go right to Facebook, which allows users to report potential copyright infringements here in what is called a “takedown notice” under the Digital Millennium Copyright Act. Godspeed—and please take credit for a few of the images on those vaccine posts while you’re there.

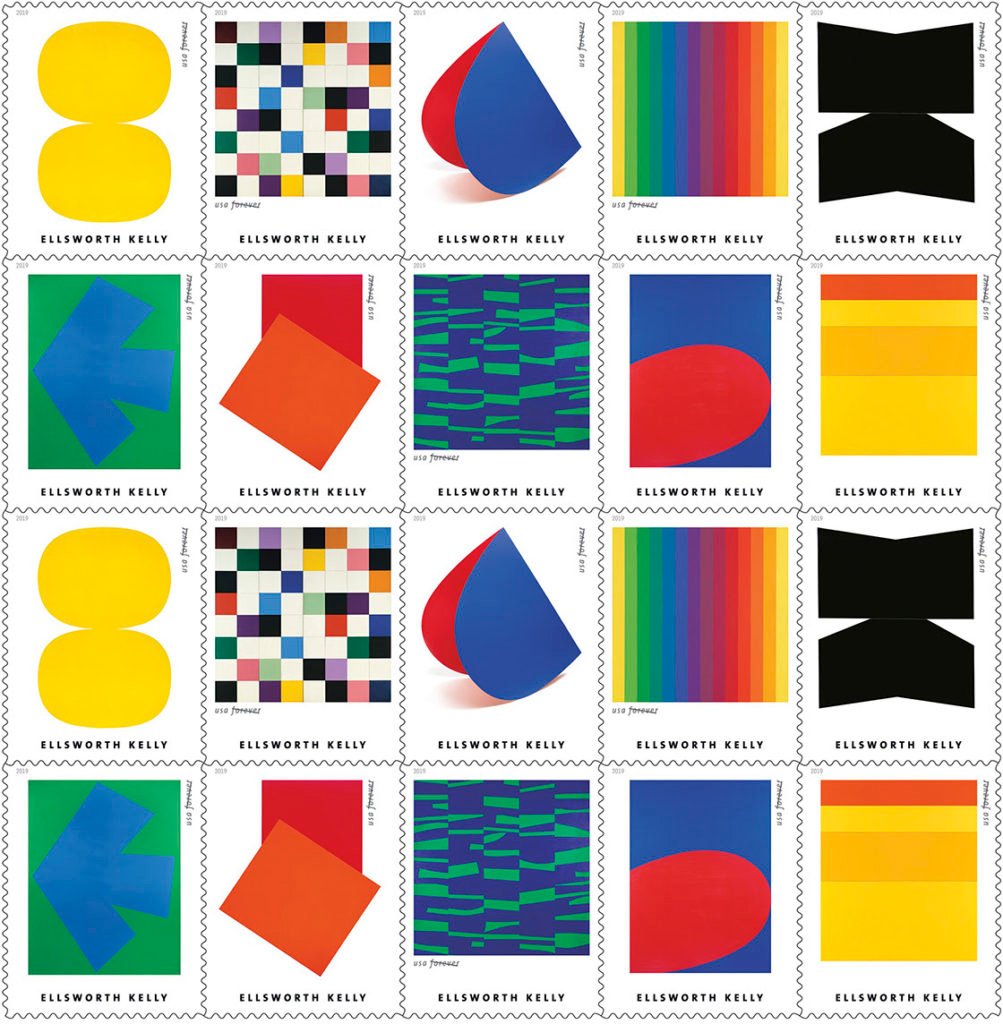

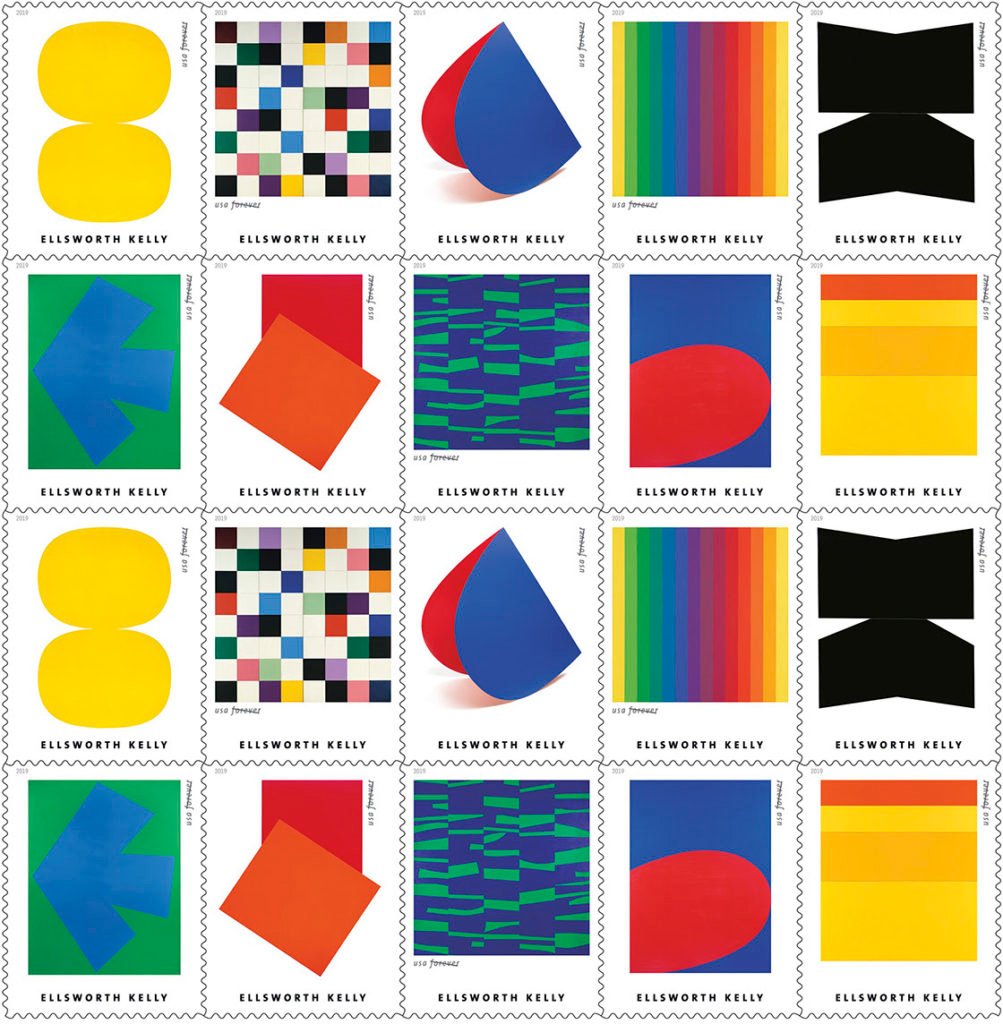

Ellsworth Kelly’s Forever Stamps. Courtesy of the USPS.

Save our post offices! But what about our stamps? I remember there was a lovely Ellsworth Kelly collection released a few years ago. How does an artwork make its way onto a stamp? Does the Kelly estate get a piece of that 55 cents?

Being asked to design a stamp is considered an honor, much the way it used to be an honor to be asked to provide an artwork for an American embassy. And the US Postal Service began using art on stamps long before the term “artist collaboration” became popular.

The first artwork licensed for an American stamp likely dates back to the 1869 Pictorial Issue. This group of stamps included recreations of John Vanderlyn’s Landing of Columbus (1842–47) and John Trumbull’s Declaration of Independence (1818). Since the mid-19th century, the Postal Service has branched out from reproductions of works by dead white guys who painted dead white guys to stamps featuring the handiwork of Mary Cassatt, Isamu Noguchi, and, most recently, Ruth Asawa.

Such collaborations are made with the approval of the artist or estate. If permission is not granted and the Post Office goes ahead with the stamp anyway, it can sometimes be quite lucrative for the artist to sue. Consider two recent cases in which the USPS treated the copyright clearances like a forgotten package.

The first concerns the Korean War Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC, whose sculptor was awarded more than $500,000, or 10 percent of the revenue from the stamp that featured the design. The second case revolves around a photograph of the Statue of Liberty—except it wasn’t the actual Statue of Liberty, but the “sexier” replica at the New York-New York Hotel in Las Vegas. The designer of that version, a guy named Robert S. Davidson, was promptly awarded $3.5 million.

Those are the exceptions that prove the rule. Let’s hear it for the USPS! Its collaborations with artists probably represent a substantial portion of the art that most Americans are able to see in a given year. Vote!