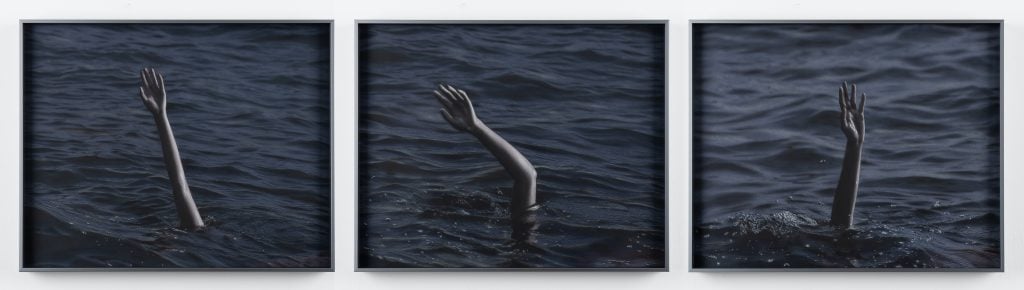

In the images, a foot extends out of the water and glides overhead, as if a lone synchronized swimmer were doing a backflip. According to Hong Kong’s Gallery Exit, the series is inspired by Alfred Hitchcock’s film Frenzy. But for those who have witnessed the upheavals in Hong Kong over the past 15 months, the photographs by the young artist Man Mei To suggest something very different. They bring to mind the demise of the 15-year-old student protester Chan Yin-lam, whose naked body was found in the sea last September. The cause of death remains a mystery after an inquest last month.

“Everyone knows what it means,” 30-year-old Man tells Artnet News, “and viewers can contextualize the work referring to their own experiences.”

Across the city, young artists in their 20s and 30s are filling galleries with art that reflects—subtly—on Hong Kong’s tumultuous recent history, from the fierce protests sparked by the now-withdrawn extradition bill last summer to Beijing’s imposition of a sweeping national security law that critics say has restricted free expression to the coronavirus pandemic that has shut down Hong Kong in fits and starts.

Protests against the National Security Law in Hong Kong on July 1, 2020. (Photo by Katherine Cheng/SOPA Images/LightRocket via Getty Images)

One year ago, Abby Chen, the head of contemporary art at the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco, told Artnet News that the city’s battle for freedom and against systemic brutality—campaigns that have since spread around the globe—could produce the greatest art in Hong Kong’s history.

Local artists, she suggested, would set out on a journey similar the one mainland Chinese artists went on in the 1980s, a period that produced some of the country’s best contemporary art. The works saturated with codes and symbols that have recently emerged from Hong Kong suggest that the city’s artists are, indeed, heading in this direction. “There is so much power in the dire situation,” Chen says.

A New Generation Rises, Under New Rules

Works that dive deep into the trauma of this era could chart a new course for Hong Kong’s art, experts say, demonstrating a novel approach to visual language that will set this generation apart from its predecessors. Some artists are feeling renewed conviction to make work that speaks to the moment. “When everyone is going through disastrous times, art becomes an important record of history,” Man says, “a kind of record that documents our collective emotional trauma.”

The contributions of artists, however coded, are significant given that a chilling effect has spread through Hong Kong in the three months after Beijing’s imposition of its national security law, which prohibits “secession, subversion of the state, terrorism, and collusion with foreign forces.” Although freedom of speech is enshrined in the Basic Law, Hong Kong’s mini-constitution, the broadly defined rule has spread fear and confusion.

Books written by pro-democracy activists have been purged from public libraries. Chanting and displaying protest slogans could get one arrested. The de facto protest anthem “Glory to Hong Kong” has been banned in schools. A teacher was fired for asking students, “What is freedom of speech?” Self-censorship on social media has become the norm.

This month, a large crowd flocked to the government-run Museum of History to catch a final glimpse before it closes for a two-year revamp, sparking fears that the display dedicated to the history of the city will never be the same.

Parallel Space in Hong Kong, where Giraffe Leung‘s work is on view.

In this context, fine art offers a sanctuary of sorts. Giraffe Leung, whose work tackles the city’s politics, didn’t expect galleries or institutions to feature his work following the passage of the law. But his first solo exhibition opens at an alternative art space in the city this month.

A New Purpose for Art-Making

Many artists in Hong Kong found themselves unable to create over the past year, when what started out as a peaceful protest against a single bill morphed into a pro-democracy movement that saw violent clashes between protesters and riot police. As the government continued to ignore demands for an inquiry into police’s use of force, “some artists thought that art was useless,” says Kurt Chan, a veteran artist and a professor of fine art in Hong Kong.

But the arrival of COVID-19 has given artists time to process their experiences in isolation. What has resulted is a wave of powerful allegorical works dealing with life under great political pressure. For artists like Cheng Yin Ngan, painting has become a form to question, challenge, and experiment rather than simply an opportunity to showcase what she learned in art school.

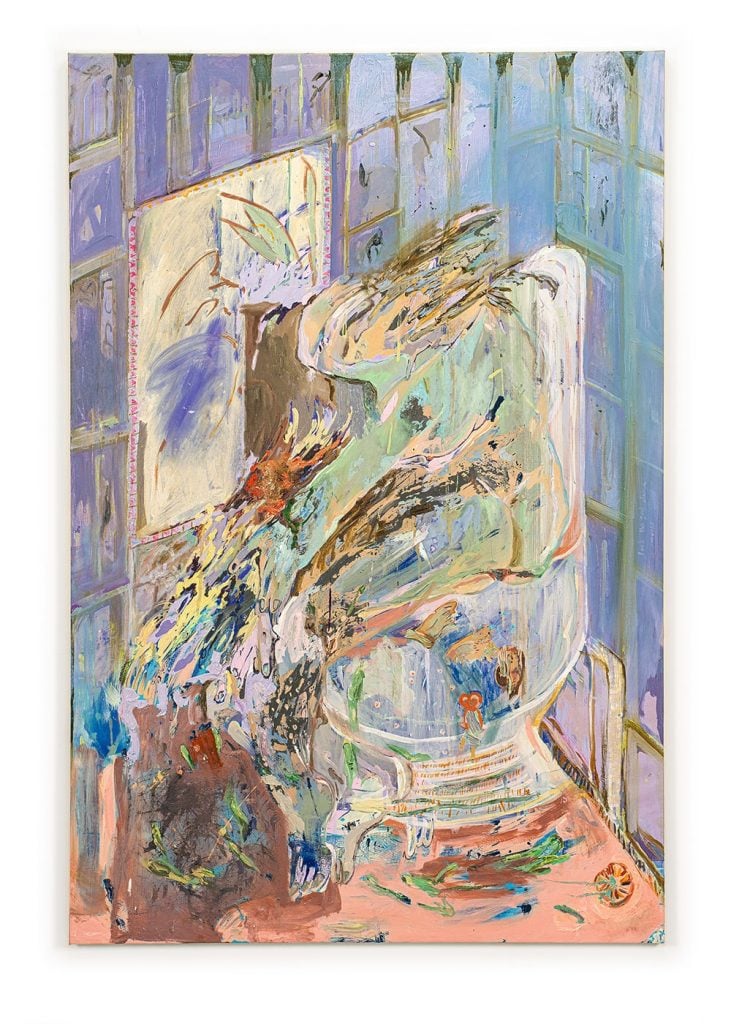

Cheng Yin Ngan, Searching for hand hand (2020). Courtesy of the artist and Blindspot Gallery.

Cheng’s new work, on view in a solo exhibition at Blindspot Gallery (through October 24), embodies this evolution. It was during a residency at the gallery over the summer that she picked up paint brushes for the first time in six months. Prior to the protest movement, the 1995-born artist approached paintings like a monologue, “trying to find something out of an uneventful life to talk about.” Feeling a lack of connection with others, she was reluctant to portray human figures, preferring objects like boats and houses, which allowed her to show off the techniques she acquired in art school.

Since witnessing the protests and seeing “the real world,” she has changed her approach—and thrown some of her academic lessons out the window. Human figures have taken center stage. “I’m no longer observing [people] from a distance,” she says. “In these new paintings, I’m a part of them.”

Cheng Yin Un, Beer Weed and Spinach (2020). Courtesy of the artist and Blindspot Gallery.

In the painting Teenage Girl With Bricks, young female protesters dig bricks out of the street to throw at police—Cheng’s way of questioning the gender dynamics of the protests, where women were often told by their male counterparts to stay away from the danger zone. In Beer Weed and Spinach, the artist looks back at the night she collapsed in the bathroom as the world outside seemed to be falling apart.

The response to her new body of work has been unlike anything Cheng has experienced. By creating images that act as a visual diary of what she witnessed firsthand, she aims to put “together the pieces that are not taken into account in the so-called ‘official history,’” she says. “This is what we artists can do.”

A New Role for the Audience

Some of the most exciting new work to emerge in Hong Kong is tied even more literally to what happened in the streets. Artist Giraffe Leung created a series of street artworks, titled “Paper Over the Cracks,” in which he used yellow tape to frame the protest graffiti that had been painted over by government workers. The images, which highlighted the absurdity of the city’s streetscape, became a social-media sensation; before long, anonymous citizens were creating their own versions with colored tape. The project caught the attention of the alternative art venue Parallel Space, which is giving the 27-year-old his first solo exhibition this month.

Installation view, Giraffe Leung “Paper Over the Cracks.” Courtesy of the artist.

The show presents mixed-media works that point to Hong Kong’s precarious position. In Hong Kong is the World, Leung meticulously collaged five world maps to re-create a map of the city, illustrating Hong Kong’s identity as an international, multicultural society. He also questions the truthfulness of the media in Black and White, twin light boxes containing collages made from local newspapers across the political spectrum.

“Before the movement, I looked at Hong Kong from a third person’s perspective,” Leung says. “But over the past year, I feel that I’m part of the society, and I tell people how I see the city through my work.” Still, he says, “I need the audience’s understanding… to make my art meaningful.”

Observers note that the current situation requires a different relationship between artist and audience. When creators must communicate in code, the viewer has to put in the time to understand the message. In a moment when travel is limited, it also helps crystallize the purpose of art for these young creators: they want to communicate with those who have been through what they have been through.

“It’s not just about what the artists want to say, but what the audiences want to say, too,” Kurt Chan says. “Together, they collectively define the work.”

Installation view, “Mark Chung: Wheezing” Courtesy of de Sarthe and the artist.

This dynamic was evident in artist Mark Chung’s recent show at de Sarthe, where he dismantled the gallery space to create an immersive installation that evokes the uncomfortable emotional rollercoaster he experienced over the past year. Chung rearranged the gallery’s air-conditioning system to expose the room’s inner workings, usually tucked behind the wall, as a way to mirror the state of Hong Kong, which had been thrown into turmoil to expose a hidden political agenda.

“There’s a story to tell,” Chan says. The works flooding Hong Kong’s scene “might be raw,” he admits, but they also represent “an explosion of creative power among young artists.”