Opinion

How Art History Can Help Explain the Stunning Rise of Conspiracy Theories That Is Defining Our Time

This is the second half of a two-part series on art theory and conspiracy theory.

This is the second half of a two-part series on art theory and conspiracy theory.

Ben Davis

This is the second part of a two-part essay on conspiracy theories. The first part is here.

Earlier, I looked at how “conspiracy thinking” could be made sense of in relation to a broader spectrum of thought. In this part, I want to look at what recent art trends can tell us, by analogy, about the appeal of conspiracy theory.

This is really the most elementary point, but it must be said anyway: From the sinking of the Battleship Maine to the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment to the Jeffrey Epstein sex ring, history provides unrelenting testimony to the fact that whatever dark thoughts you have about what goes on behind the scenes with the wealthy and the powerful, the truth is likely worse, much worse. Real conspiracies are the soil in which “conspiracy theory” grows.

The latter term, though, is conventionally used dismissively to reference what other people believe. Yet it turns out that no community really has a lock on conspiracy thinking.

Reams have been written on the circulation of conspiracy material in hip hop, for instance. Travis L. Gosa argues that all the New World Order, 9/11 Truther, and Illuminati references (among many others) in hip hop respond to the real experience of racist oppression, flow from the scene’s emphasis on ground-level experience over “experts” associated with a hostile system, and, most intriguingly, that dabbling in the “cultic milieu” is actually part of how the music maintains countercultural cachet in the face of commodification.

In a very different register, it is quite clear that MSNBC liberals are not immune to the allure of a good conspiracy. Last year, I wrote an essay on an astonishingly improbable theory that was then gaining traction that Leonardo’s Salvator Mundi was sold as part of a plot by the Russians to aid Donald Trump.

I want, however, to focus on a different example, specifically because it points to some of contemporary art’s best capacities for grasping unfamiliar ways of thinking.

In an essay I wrote and on a podcast I spoke on for this site, I have spent a lot of time picking over a virulent online conspiracy theory that performance artist Marina Abramović is at the center of a vast cabal of Satanists who control the entertainment industry. These theories seem to me horrifying (not to mention, if you scratch the surface at all, steeped in dangerous misogyny).

There is, however, just one inconvenient factor that I’d have to reckon with, were I to try to make this case to a public beyond the art audience. And that is the fact that the art world quite clearly is in the grips of a romance with the occult—not a Satanic, baby-eating orgy behind the scenes, but a flirtation with New Age revelation, right out in the open.

Installation view of Hilma af Klint at the Guggenheim. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

This vogue has been one of the defining trends of recent years, with immense museum crowds turning out for shows of Victorian spiritualist Georgiana Houghton in London and Swedish mystic Hilma af Klint in New York. It was quite literally the last thing I wrote about before lockdown began, via the subject of the Whitney’s spotlight on Agnes Pelton, the “desert transcendentalist” who believed she communicated with spirits through her airy, odd, semi-abstract paintings.

Agnes Pelton, Resurgence (1938). Image: Ben Davis.

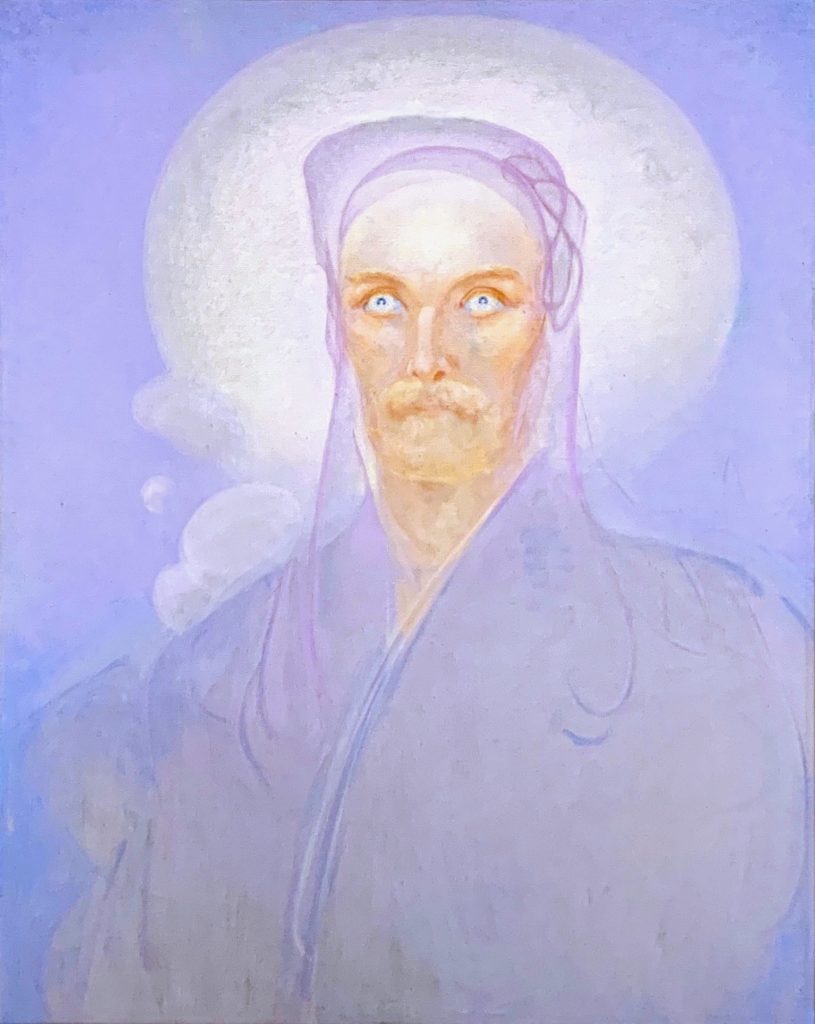

Pelton was, among other things, inspired by the Agni Yoga doctrine of Helena and Nikolai Roerich. A burning-eyed portrait of Nikolai was an unsettling note in the otherwise ethereal Whitney show, and another painting may have been of Helena, who claimed to channel otherworldly wisdom directly from the spirits. Nikolai was a fascinating figure, a painter and set designer (he did the scenography for Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring”), who was also an adventurer and mystic. His association with Henry Wallace, FDR’s 1940 VP pick and the ultimate New Deal true believer, touched off a minor political scandal when foes threatened to leak his adoring correspondence with the guru to the public—a distant echo of the #SpiritCooking scandal that snared Abramović and John Podesta in 2016.

Agnes Pelton, Barna Dilae (1935). Image: Ben Davis.

The press on such museum shows tends to water down what these various artists actually believed into some vague, Instagram-friendly “spirituality” for popular consumption, rather than getting too into the weeds of what they believed. But in general, one has to think that the popularity of this rediscovered mystical art is very much on account of, not in spite of, its promise of esoteric meaning. The Occult Turn in art is just one expression of a much larger recent popular turn towards alternative spiritualities and witchcraft, with sales on “mystical services” reaching $2.2 billion in 2018.

When critic and art historian Eleanor Heartney recently explained the surging appeal of magical art, the factors were pretty much the same as those I gave for the appeal of conspiracy theory in part one of this essay: a generalized sense of hopelessness about the social order that leads to a hunt for new narratives of empowerment; a feeling of encroaching chaos that amplifies the appeal of alternative codes of meaning to give an order to it all; a disenchantment with soulless commercial culture that leaves people looking to attach themselves to the romance of secret knowledges.

Astrology functions, if you think about it, very much like the revelation of a cosmic conspiracy. It is replete with esoteric graphs and charts, a sense of meaning both universe-spanning and intimately concerned with your personal affairs, and the revelation that behind the fluctuations of history there are just a few immutably repeating archetypes.

The first newspaper astrology column, “What the Stars Foretell for Princess Margaret” by R. H. Naylor, appeared in 1930 in Britain’s Sunday Express—a time when the traumatizing global fallout of Wall Street’s sudden collapse gave the ability to foresee the future a particular appeal. As one account puts it: “The early horoscopes read more like Nostradamus than Dear Abby. Astrologers worried about political events, about war, famine and pestilence.”

Last year, writing in the New Yorker, Christine Smallwood quoted an astrologer on the surge of interest in star science following the 2008 crash: “All of those structures that people had relied upon, 401(k)s and everything, started to fall apart. That’s how a lot of people get into it. They’re like, ‘What’s going on in my life? Nothing makes sense.’”

The 2016 election intensified these energies. “In the Obama years people liked astrology,” another astrologer told Smallwood. “In the Trump years, people need it.” That energy is likely to swell further now, at a time when we are suffering a “global narrative collapse,” and the sudden plunge into the darkness leaves massive numbers of people looking for any light to guide them to safety.

Two years ago, the Metropolitan Museum Art’s “Everything Is Connected: Art and Conspiracy,” curated by Douglas Eklund and Ian Alteveer, stands out as an attempt to look at recent art history through the theme of conspiracy theory. It was received in relationship to the shock electoral triumph of birther enthusiast Donald Trump and talk of the “post-truth” condition. But the show was inspired by a challenge from the late LA artist Mike Kelley, bard of all things traumatic and cast-off.

Mike Kelley, Educational Complex (1995), seen in “Everything Is Connected.” Collection of Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

“I don’t think that there’s anybody in the academic world who will even go near conspiracy theory at this point,” Kelley remarked in a 1992 interview. “Once it starts to become obvious how it is a motivating factor in real life, then people will start to write about it as a mythology or an ideology.”

The early ’90s was a telling moment to open a conversation on the subject. The Cold War had just ended. Very serious people were talking very seriously about the “end of history“: there were no more big ideologies to motivate people; left and right could converge in a “Third Way” era of technocratic government; globalization and neoliberalism would continue unfolding forever with a logic so ironclad that it didn’t even really have to explain itself. In art and in the academy, this was the high water mark of “postmodernism,” which arrived as a philosophical admission of the “Death of Master Narratives.”

Kelley had a wonderful antenna for all that was repressed by a middle-class culture of consumption and respectability and disembodied intellect, and how it tended to return in displaced form with an eerie, intensified power (his reflection on conspiracy theory actually appears, somewhat out of the blue, between reflections on how the term “folk art” conceals conservative ideology and how dolls are monstrous if you really look at them). He correctly predicted a flourishing of interest in conspiracy theories, which would be emblematized by the pop-culture sensation of the X-Files, which launched the next year.

Well, conspiracy theories are, exactly, “master narratives.” They imagine the broken pieces of the world as a puzzle that promises revelation, if you just piece it together. And the increasing sway they have had on public life up to the present can be seen as the return of the repressed when it comes to ideology—if the technocratic centrists don’t offer a story, or the story they do offer doesn’t reflect emotional reality for a large number of people, then a story that makes sense of that reality will be invented.

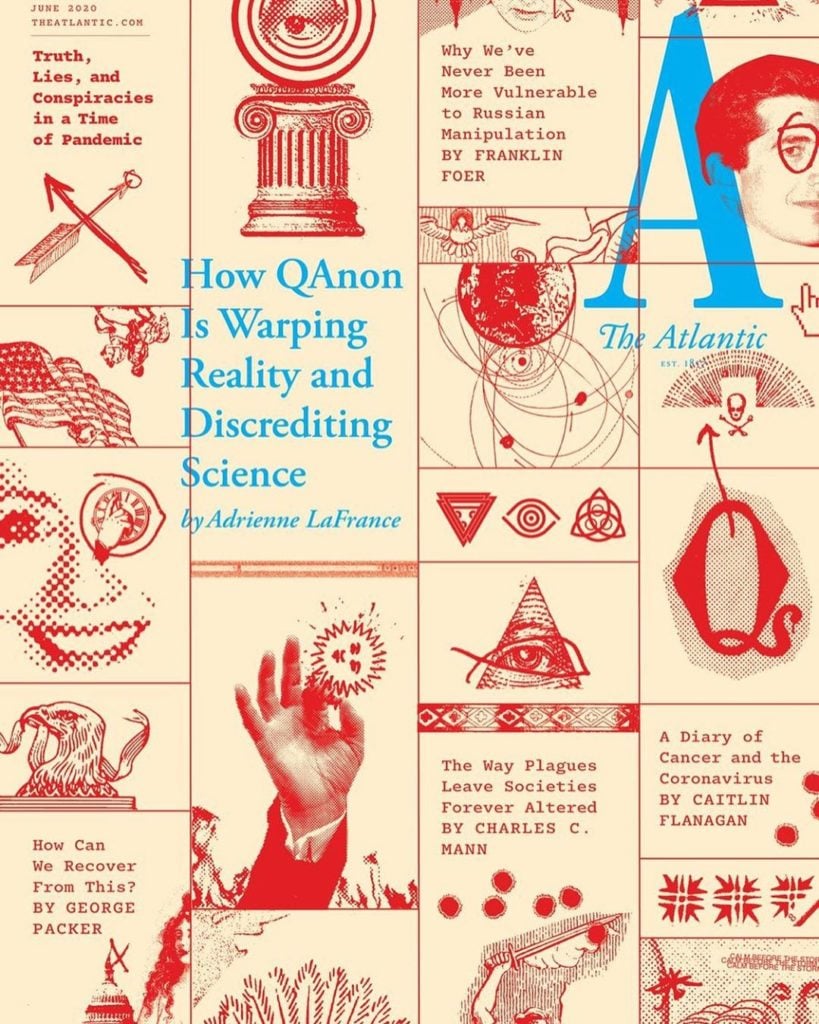

The Atlantic has just put out an entire “Conspiracy Theory” issue. Adrienne LaFrance’s cover story argues that the QAnon-inspired belief that Donald Trump is locked in a secret war with a deep state cabal of child molesters is on its way to becoming something like a religion.

The Atlantic‘s June 2020 issue on conspiracies.

It’s a colorful account—but the line that jumps out at me is this one: QAnon, LaFrance writes, “is a movement united in mass rejection of reason, objectivity, and other Enlightenment values.” Even given QAnon’s strong evangelical component, I don’t think this is what LaFrance’s article actually shows.

Almost everyone thinks of their own beliefs as reasonable, in one way or another, and no community recognizes itself as being held together by irrationality. The people LaFrance talks to often say they are motivated by “research” and “thinking for themselves” rather than accepting what the media tells them. Consider this: The Atlantic’s own editor, Jeffrey Goldberg, infamously helped promote the narratives that let the Bush administration conspire us into the Iraq War, scarring the lives of a generation of Americans—so it’s actually irrational, when you think about it, to stigmatize distrust of the “objective media” as irrational.

The article’s toss-off reference to “Enlightenment values” mainly makes sense as an appeal to the presumed readership’s self-conception as enlightened, rational, immune to conspiracy themselves.

In his book Ideology: An Introduction (published, it so happens, in 1991, the same end-of-history era when Kelley made his remark), Terry Eagleton distinguished “criticism,” which put its faith in the raw power of facts, with what he called “ideology critique”: “’Criticism,’ in its Enlightenment sense, consists in recounting to someone what is awry with their situation, from an external, perhaps ‘transcendental’ vantage-point. ‘Critique’ is that form of discourse which seeks to inhabit the experience of the subject from inside, in order to elicit those ‘valid’ features of that experience which point beyond the subject’s present condition.”

Why does this perspective-shift matter? Because elsewhere in the Atlantic, the communication experts that the magazine’s own writers talk to explain that the most basic operation, if you are trying to stop the spread of dangerous disinfo, is to first of all distinguish between “true believers” and the broader, looser class of the “curious” and “uncertain.” You probably can’t win the true believers—but if you want to starve them of converts, the last thing you want to do is approach the wider layer of people via lecture, shaming, and ridicule. That tends to harden belief, sending people looking for sympathetic information sources to fight back. You want instead, the researchers say, to try to find some point of identification. The anathemizing perspective that frames “conspiracy” as blind cult thinking that only other, irrational people engage in makes these tricky tasks harder.

Something like QAnon is an entirely more apocalyptic phenomenon than the kind of arty occultism that has fired the imagination of museum-goers in recent years. The former is essentially a pro-Trump mythology whereas the latter’s underlying politics are a spiritualized feminism.

Another way to put that is that the people who are drawn to the latter are more familiar, in their starting values, to a museum crowd. The point of reading the two together, for me, is to say that you may already intuitively understand how a seemingly unintelligible phenomenon works better that you think you do.

When LaFrance describes the appeal of QAnon as being “a very welcoming belief system, warm in its tolerance for contradiction,” that’s actually how scholars have also described the particular appeal of eclectic New Age philosophy for the American temperament, its “epistemological individualism” providing a kind of a la carte meaning-making activity.

A man holds a large “Q” sign while waiting in line on August 2, 2018 at the Mohegan Sun Arena at Casey Plaza in Wilkes Barre, Pennsylvania to see President Donald J. Trump at his rally. Photo by Rick Loomis/Getty Images.

And when LaFrance describes Q followers as looking to interpret cryptic online prognostications to help decipher and predict current events, it really sounds like it scratches the same itch as astrology. QAnon’s prophecies about the news are often wrong, but that fact is unlikely to make it fly apart—any more than the fact that R. H. Naylor’s astrological predictions spectacularly missed World War II stopped newspaper astrology from taking root (“Hitler’s horoscope is not a war-horoscope,” he wrote mid-1939).

For the average person in ordinary times, speculation about various conspiracies is probably more like trading wisdom gleaned from horoscopes: something that people dabble in for amusement, that connects them to other people in their circles, that gives a sense of agency or fate, that serves as a coping mechanism, that they draw from in dribs and drabs overlapping with a lot of other beliefs.

I’m not a huge fan of Crooked Media’s Hysteria podcast, which has a kind of faux hip Beltway tone that I can’t take. I’m glad I tuned in to the April 22 episode, though, because it offered such a perfect example of what I am talking about (last week, the hosts were on to talking about how COVID-19 is good news for the Dems because the death of the cities will turn the suburbs blue).

There, former Obama deputy chief of staff Alyssa Mastromonaco had this to say about April’s wave of “Liberate America” protests, whose adherents she called “COVID Deniers”:

I have a very good friend who is a Democrat but is very conservative. She sends me a text that is like, “The fucking Democrats. They are making fun of these protests and these people are just concerned with their jobs and scared about their future.” And I’m like, “What the fuck is she talking about?” And so I did some research and I had to send her some new articles, and I was like, “You know this shit is backed by the Koch Brothers and the Trump campaign and this is just fucked up—this has nothing to do with people and their jobs.” This is just some bizarro liberty argument that is really just Donald Trump wanting to get the economy back so that he can have a reasonable argument for running for president.

Well, the Liberate protests are definitely astroturfed. And definitely dangerous: the premature reopening they have sped along will lead to thousands of deaths.

But the people stoking this fire aren’t totally stupid either. They see an opening. Their campaign wouldn’t actually attract people if it didn’t potentially touch a nerve that was raw.

Protestors pray near Governor Charlie Baker’s residence during a Reopen Massachusetts Rally on May 16, 2020 in Boston, Massachusetts. Photo by Maddie Meyer/Getty Images.

What strikes me about Mastromonaco’s frustrated rant is that, by her own account, she is presented with human proof that pundits “making fun” of the protests is backfiring. The images of the demonstrations are alarming, the forces behind them sinister—but in her unnamed friend, she has actual evidence that not everyone potentially picking up the message is either a hardcore reactionary or a grifter.

And her response is to continue to make fun of the protests (the name of the episode was “We ALL Want Haircuts, Karen,” boldly addressing an audience that is clearly not the show’s audience, while being sure to piss off anyone like her friend).

Instead of the moral of the anecdote being “these protests seem to be more attractive to people we want to win than we thought; recalibrate,” the moral seems to be that if you just rationally prove that the #LiberateAmerica message should only appeal to people utterly unlike you, then the problem is solved.

The kernel of rationality in the Liberate America protests is plainly that society is wounded and there has seemed to be no credible plan besides “stay home, listen to the experts” to get us through months and months of pain with no promise of anything better on the other side. “It is irrational to reopen now” is not a narrative that people can connect to a vision of a future for themselves if they see only hardship looming.

A nurse wears personal protective equipment as she performs range of motion exercises on a COVID-19 patient in the Intensive Care Unit (ICU) at Sharp Grossmont Hospital amidst the coronavirus pandemic on May 5, 2020 in La Mesa, California. Photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images.

The fact that fantasies of a secret Bill Gates/Anthony Fauci cabal conspiring to keep America idle for nefarious ends is gaining wider and wider traction has to be seen as an indictment of more than Trumpian brain rot. It is also a symptom of the fact that the political mainstream—what Tariq Ali calls the “extreme center”—has no ready narrative that might feel like a credible step towards salvation. In the resulting void of despair, all kinds of diabolical thoughts gain traction, as people look for any kind of incantation to cast to part the clouds and are drawn to the people who are chanting the loudest.

Not so far beneath the surface of the mockery of the Liberate protests, you sensed a cynical hope that these misguided crowds, at least, will spread the virus among themselves and die. “You can’t gaslight a pandemic,” the saying goes. Or I think people not so secretly hope that the experience of the coronavirus’s lethal, non-negotiable reality will turn the masses against Trumpian fabulation, snapping discourse back away from the dead end of conspiracy and onto the rails of reality.

But in the absence of any strong counter-narrative or plan to rally the common human passion for survival around, you don’t have a strategy. You have a weird mix of contempt and your very own brand of magical thinking.

Most importantly, if the function of conspiracy theories in the first place was to provide a graspable narrative to navigate a painful reality that doesn’t seem to make sense, then the encounter with still more pain and more senselessness is very likely to deepen the fever rather than to cool it.

That’s a prophecy, by the way: the myths we see moving people now are as nothing compared to those we will have to take seriously in the times to come.