Op-Ed

Artists Can Help Us Imagine a New Relationship with the Earth. That’s Why We Need Their Voices at COP26

Art and science are partners in this urgent conversation.

Art and science are partners in this urgent conversation.

Christopher Smith

One of the most famous images of German romanticism is Caspar David Friedrich’s painting from 1818, Wanderer above the Sea of Fog. A man with his back to us stares out over a mountainous landscape. His thoughts are unknowable, the landscape is sublime yet empty—it is nature at its most inscrutable.

This image reminds us of the unique ability of art to question the relationship between humanity and nature. And it is because of this ability that we must ensure that art has a place at high-level climate discussions such as COP26, the United Nations Climate Change Conference summit taking place in Glasgow this month. Our task must be to adapt and mitigate. We need to think through how to live in a broken world and how to begin to mend it. Here, arts and humanities are key alongside political action and scientific education.

There are three ways in which art is core to helping solve the climate emergency, the most pressing challenge facing the globe.

An LED installation by artist collective Still/Moving projects a message across the River Clyde to delegates attending COP26 on November 03, 2021 in Glasgow, Scotland. Photo: Christopher Furlong/Getty Images.

Artistic expressions of the devastating challenge of climate change offer an immediacy that graphs and data, which are often complex or overwhelming, cannot match. It is artists who can bring simplicity to the message. I remember hosting Wolfgang Buttress, the brilliant artist and architect behind the Hive sculpture that is currently in Kew Gardens, when it was chosen as part of the British Pavilion for the World Expo in Milan in 2015. As part of the UK events around the Expo, Buttress presented a three-minute film of his soundscape of bees and light, and most of the audience was in tears, moved to the core by the music and the extraordinary complexity of the creatures’ behaviour. The takeaway was clear: Without bees, there is no humanity.

No words or data could communicate as poignantly as that film—and that is just one example of how art has a specific power to change perspectives and behaviour. If we want the innovation being created in the fields of environmental science to really catch hold, we need strong messaging. And it is precisely for that reason that art, like John Gerrard’s Flare Oceania, are rightfully being showcased alongside COP26 in Glasgow. They will be essential to sustaining thoughtful pressure on ourselves and our leaders.

A couple stands underneath Wolfgang Buttress’ illuminated Hive Installation at Kew Gardens in London, England. Photo: Jack Taylor/Getty Images.

The system is broken, but we are still part of it. Art, which reflects us back at ourselves, reminds us of this. We must insist on our position in this complex world—we cannot survive elsewhere. Yet more of us are living in cities, and few of us can or should travel to the most endangered of parts of this world to experience them. Many people today see little of nature or the realities of our impact on the natural world.

Artists can transport us to these places and render them unforgettable. Last year, artist Adam Laity was presented with the award for Best Climate Emergency Film at a recent virtual ceremony held by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), the UK’s national art research funding agency of which I am executive chair. Laity’s work, called A Short Film About Ice, combines stunning visuals and aerial footage of Arctic landscapes with poetry and literary extracts from authors such as Lord Byron and Allen Ginsberg. This is a place where most of us will never travel to, but we must consider it—it is where we are seeing some of the most drastic effects of climate change.

Touching on themes of cultural responsibility and eco-anxiety, Laity’s work shows us that humans and nature are interconnected in ways that are hard to understand, and that the lack of understanding has caused the break-down of our global climate system.

Still from Adam Laity’s A Short Film About Ice. Courtesy the artist and the AHRC.

These are two poles of a crucial dialogue over the relationship of humanity and the natural world, which has been a critical theme for art. In different ways, two of the most famous English artists, J. M. W. Turner and John Constable, placed the human as a tiny figure within vast landscapes or seascapes; mastered not mastering. Sculptor Andy Goldsworthy’s landscape interventions challenge notions of what is a real or an artificial landscape and focus our attention on the passage of time.

Each of the three examples uses scientific research. Turner and Constable were fascinated by optics and meteorology; Goldsworthy researches archaeology and Laity worked closely with the scientists from the British Antarctic Survey. Art and science are partners in this shared conversation.

Installation view of Hyundai Commission “Anicka Yi: In Love With the World” at Tate Modern, October 2021. Photo by Will Burrard Lucas.

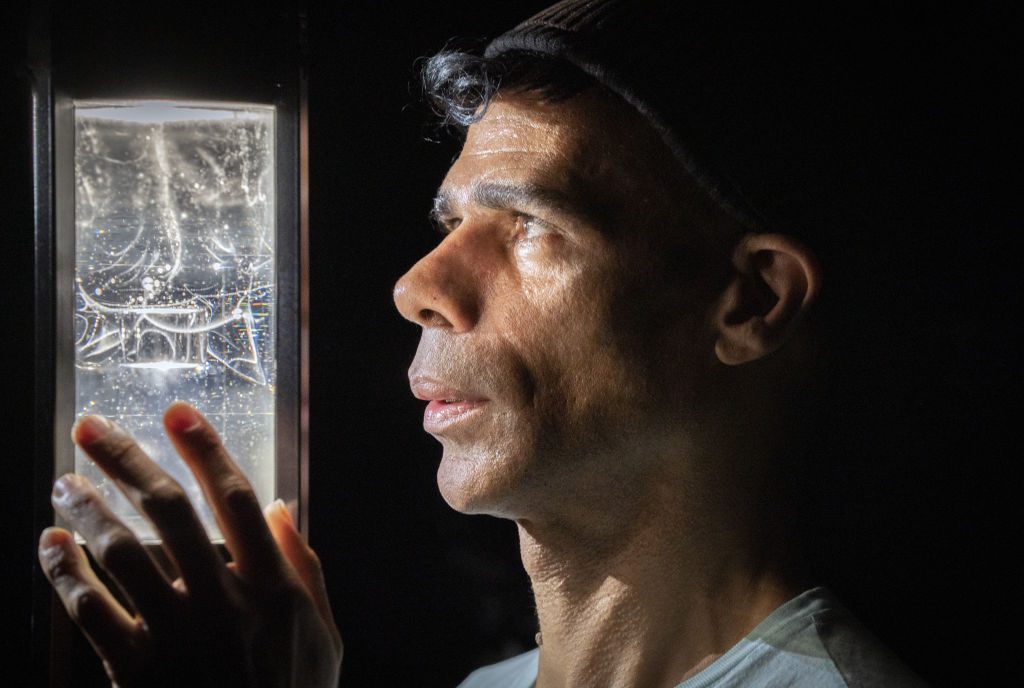

Running concurrently to COP26 at the Glasgow Science Centre, artist and AHRC-funded art researcher Wayne Binitie, is displaying a piece of the Antarctic ice core which contains within it air captured from 1765, a key final moment of the pre-industrial era. We now know that ice cores contain traces of growing pollution—in Binitie’s work, you can see the impact of the amount of fuel burnt to support the Roman empire’s economy.

As this piece of ice slowly melts, it releases air from a time before machines and we are forced to reflect on our history, the impact we have had on our world, and the shocks to the Earth’s system which we have inflicted. It is an example of the collective conversation that we can encourage when art takes centre stage at crucial moments for climate action, and especially when art is in conversation with science, giving it shape and visibility, translating it into immediacy, and feeding back into core questions.

Sculptor Wayne Binitie looks at his glass sculpture containing air from the year 1765 which is on display at a new immersive exhibition ‘Polar Zero,’ created in collaboration with British Antarctic Survey and global engineering and design firm Arup, at the Glasgow Science Centre to coincide with the Cop26 summit. Photo: Jane Barlow/PA Images via Getty Images.

The arts have rightly taken a central place at key climate summits, for art has always shown us to ourselves—it is an unflinching mirror. Art is as important for policy makers as it is for the rest of us. And we need to see far more of this, but not only as illustration Rather it is precisely the role of the artist as a thinker and a radical that we need to see more of, not depicting other people’s debates but asking the questions we need to ask and answer, and sometimes are too keen to avoid.

Caspar David Friedrich portrayed a man alone before nature. Today, all of us need to face up to what we have done to our planet, and what we now need to do.

Christopher Smith is a professor and executive chair of the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC), the UK’s national art research funding agency.