Art Criticism

‘Foreigners Everywhere,’ Unpacked: What a Biennale Built on Cosmopolitan Myth-Making Leaves Out

Part 2 of a 3-part essay on the 60th Venice Biennale, curated by Adriano Pedrosa.

Read Part 1 of “‘Foreigners Everywhere,’ Unpacked” here.

Queerness and Nowness

In 1978, Rio de Janeiro’s Museum of Modern Art burned down. The important Brazilian art critic Mário Pedrosa (no relation to Adriano, as far as I know), famously proposed that it should be rebuilt as a complex of five museums: the Museum of the Indian, the Museum of Virgin Art (Museum of the Unconscious), the Museum of Modern Art, the Museum of Black People, and the Museum of Folk Arts.

That didn’t happen, but in its basic outline, this list corresponds strikingly to the disparate interests of the 60th Venice Biennial—Indigeneity, folk and “outsider” art, and art by artists of color with a focus on the African diaspora. The notable missing piece: the “Museum of Modern Art.” In his proposal, Mário Pedrosa thought that institution should focus on the lineage of Brazilian artists who studied traditions coming out of Impressionism, up through Concretism and Neo-Concretism, while incorporating the broader world of Latin American modernisms and “American and European rooms” to show influences and interchanges.

In the 2024 Venice Biennale, that tradition of modern art has become completely submerged as a resource of inspiration. In the show’s list of core themes, what has replaced modernism as a narrative of progress, seemingly, is the celebration of queer art.

Louis Fratino, An Argument (2021) and Bhupen Khakhar, Fishermen in Goa (1985). Photo by Ben Davis.

As I argued in Part 1, “Foreigners Everywhere” feels deliberately distant from the mainstream of the art market. The artists in the show who might be said, by dint of their career success and previous gallery exposure, to be most representative of the industry of “contemporary art” are Salmon Toor and Louis Fratino—both accomplished and in-demand New York-based figurative painters with a particular focus on scenes of gay intimacy.

When the show’s general turn to craft, folk, and ritual arts for authenticity encounters productive friction, it is in works that set out to queer tradition or tweak gender hierarchies. In her paintings, Violeta Quispe employs the style of art traditionally associated with her ancestral home in the Sarhua region of Peru, but she populates them with gender-fluid demigods and gay rights activists. Norway-based Ahmed Umar has made a video of himself performing an erotic dance traditionally reserved for young brides in his native Sudan. Ana Segovia has an archly camp video of two men, in flamboyant versions of traditional Mexican cowboy costumes, engaging in ambiguously homoerotic vignettes.

Violeta Quispe, Apu Suyos (2024). Photo by Ben Davis.

Histories of modernization and sexual liberation interweave, so it makes some sense that the latter is presented as the salvageable part of the former’s progressive narrative. Considerable research shows how LGBTQI+ culture in places like Brazil as well as the United States was spurred on by modern urbanization, which opened up spaces of self-invention away from the family unit, or how the internet has accelerated the acceptance of transgender identity, providing tools of community-building and information-sharing.

Indeed, when metropolitan life takes on positive associations in “Foreigners Everywhere,” it’s most often in connection with the possibilities it holds for queer discovery. This is true of Dean Sameshima’s and Miguel Ángel Rojas’s photo series, hung facing each other, both about movie theaters as venues for gay cruising. Urban conflux and commodity culture more explicitly represent potential in Manaura Clandestina’s video Migranta (2020-23), which includes the artist staging a rooftop transgender fashion show using up-cycled materials.

One part of Frieda Toranzo Jaeger, Rage Is a Machine in Times of Senselessness (2024) at the Venice Biennale. Photo by Ben Davis.

The most exuberant image in the whole show may be Frieda Toranzo Jaeger’s stunner, Rage Is a Machine in Times of Senselessness (2024), which places a Sapphic orgy in an idyllic jungle setting, surrounded by giant cathedral-like machines. Truthfully, these particular slivery black-and-white machines read as kind of sinister to me, but I understand that this artist’s interests involve infusing sterile technology with new utopian energies.

In a show that more generally celebrates humble materials and alternative histories, the most notable outlier—sited way out in back behind the Arsenale as if to show it is an outlier—is the full-on queer futurism of Agnes Questionmark. The Italian artist purports to combine transgender advocacy with Elon Musk-style transhumanism and bodyhacking, daring the audience to “dream and fuse otherwise” via an installation of a glistening, pregnant mutant who has merged consciousnesses with a sentient operating table, represented by screens with blinking eyes on them.

Joshua Serafin, VOID (2022). Photo by Ben Davis.

On the other hand, consider Joshua Serafin’s VOID (2022), a video performance that sees a figure emerge from a black goo, thrashing and dancing and covered in oil. Serafin’s work is meant to evoke a non-binary deity figure, summoning the pre-Christian mythology of the Philippines, with its less-restrictive gender codes. VOID is pretty great, and though it in some ways resembles something you might see in a contemporary club, its overall vibe of appealing to the authority of a pre-modern past, while downplaying any association with the fallen present, is much more characteristic of this show’s intellectual project.

The Politics That Is and Isn’t There

From one angle at least, it must be admitted that the cultural position against which the decentered art history of “Foreigners Everywhere” defines itself—the one where status is signaled by restrictive fidelity to a “Western canon”—has been on the wane for some time.

In her book Entitled: Discriminating Tastes and the Expansion of the Arts (2021), sociologist Jennifer Lena explains the tendency of contemporary elites to differentiate themselves “from the narrower cultural choices of their parents’ generation” by transforming “their ‘inclusive cultural ethos’ into a marker of high social status.” An appreciation for cultural diversity, a focus on consuming art through an ethical lens, and a reflex for pointing out one’s own privilege as a way to get in front of criticism are all taught as good etiquette in high-end private-school education, and even in corporate board rooms. As Lena reiterates, “In a context in which elites do not benefit from being seen as elitist, cosmopolitan tastes provide the opportunity for voracious elites to be viewed positively.”

Now, I think an “inclusive cultural ethos” is a positive thing. The problem, then, is clarifying why you still need to develop a critical perspective on it as a language of power and authority. Let’s look at what “Foreigners Everywhere” implies that it does versus what it does.

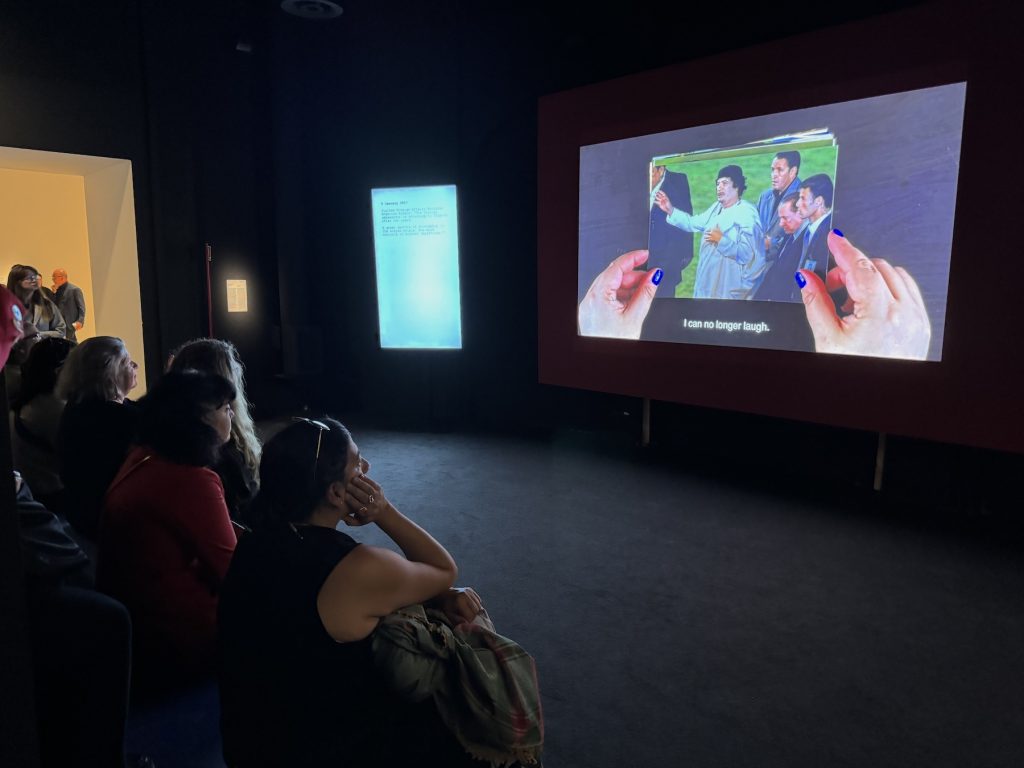

Alessandra Ferrini, Gaddafi in Rome: Anatomy of a Friendship (2024). Photo by Ben Davis.

The most in-your-face the show gets about present-day politics is in Italian artist Alessandra Ferrini’s MAXXI BVLGARI Prize-winning installation, Gaddafi in Rome (2024), a video lecture in which the artist talks about how angry she was that she was never taught about Italy’s colonial past. She draws a web of connections between Silvio Berlusconi’s opportunist alliance with Muammar Gaddafi around 2008 and the anti-migrant politics of Georgia Meloni’s Brothers of Italy party today.

This is an important beat in this Biennale. It makes explicit a political background, abstracted by the largely historical and affirmative themes of the show, but key to explaining the particularly overwhelming weight it places on art as a vehicle for progressive catharsis: the rise of neo-traditionalist, neo-nativist, neo-authoritarian politics around the world. The spectacle of an unsettling and newly assertive right is an experience common to the recent tenure of Jair Bolsonaro in Pedrosa’s own Brazil, Donald J. Trump in the United States, Meloni in Italy, and many others on both sides of the North/South divide.

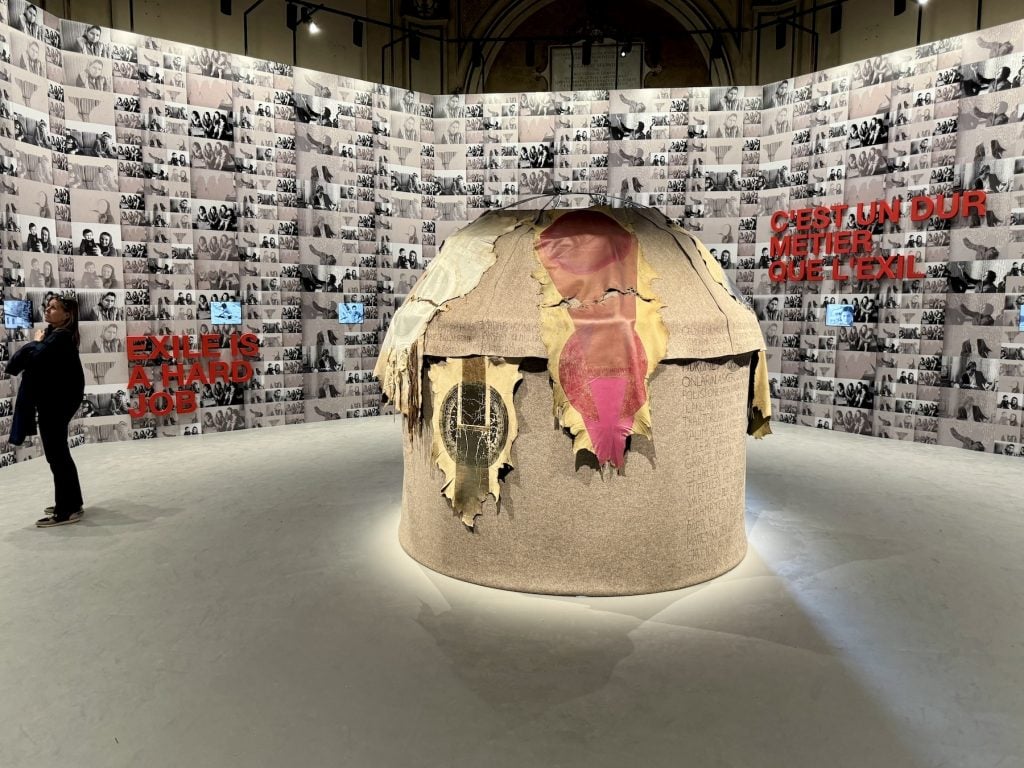

Works by Nil Yalter. Photo by Ben Davis.

Along with attacking sexual minorities, this new hard-right populism makes an aggressive demand for a return to patriotism and national tradition, fighting against rootless “global elites.” The theme of celebrating the “foreigner” that defines the present Venice Biennale obviously has to be understood against the backdrop of that menacing rhetoric.

Pride of place in Pedrosa’s show is reserved for works humanizing the migrant experience. Nil Yalter’s Exile Is a Hard Job—an installation begun decades ago, featuring interviews with immigrants and the title phrase in multiple languages—opens the Giardini section. Bouchra Khalili’s The Mapping Journey Project—a series of large hanging screens playing interviews with migrants in the late 2000s, telling the story of their perilous trips from North Africa to Europe—is a centerpiece of the Arsenale.

Joyce Joumaa, Memory Contours (2024). Photo by Ben Davis.

Yet if the sheer emphasis placed on pro-immigrant symbolism reflects anxiety about recent politics, these artworks themselves aren’t recent. They are decades or more old. Even a work newly commissioned for the Biennale, Joyce Joumaa’s video Memory Contours, focuses on restaging a discriminatory test given to immigrants more than a century ago at Ellis Island to show the “systematic stigmatization of foreigners” now. And, important as I think the subject is, I don’t think these gestures are all that trenchant as contemporary political interventions.

They push back against the worst kind of populist demonization of immigrants as faceless criminals and cheats, yes. But they don’t really challenge the self-regard of the “cosmopolitan” audience that is the most likely actual viewer of the Venice Biennale. All kinds of sophisticated and powerful people can nod along with Yalter or Khalili or Joumaa, can agree with general humanist sentiments, pay homage to the importance of immigration in history, and decry openly hateful rhetoric, while still also being pulled by other statements like, “policies that are too welcoming only encourage these dangerous migrations” or “too much unrestricted immigration will strain the government.”

Bouchra Khalili, The Mapping Journey Project (2008–11). Photo by Ben Davis.

In fact, this is what is actually happening in politics all over the world: mainstream liberal and social democratic parties are failing to provide any real political leadership on immigration beyond inconstant symbolic declarations about the need for compassion, breeding cynicism with “virtue signaling” and letting the right pose as pragmatic.

A Broken Model?

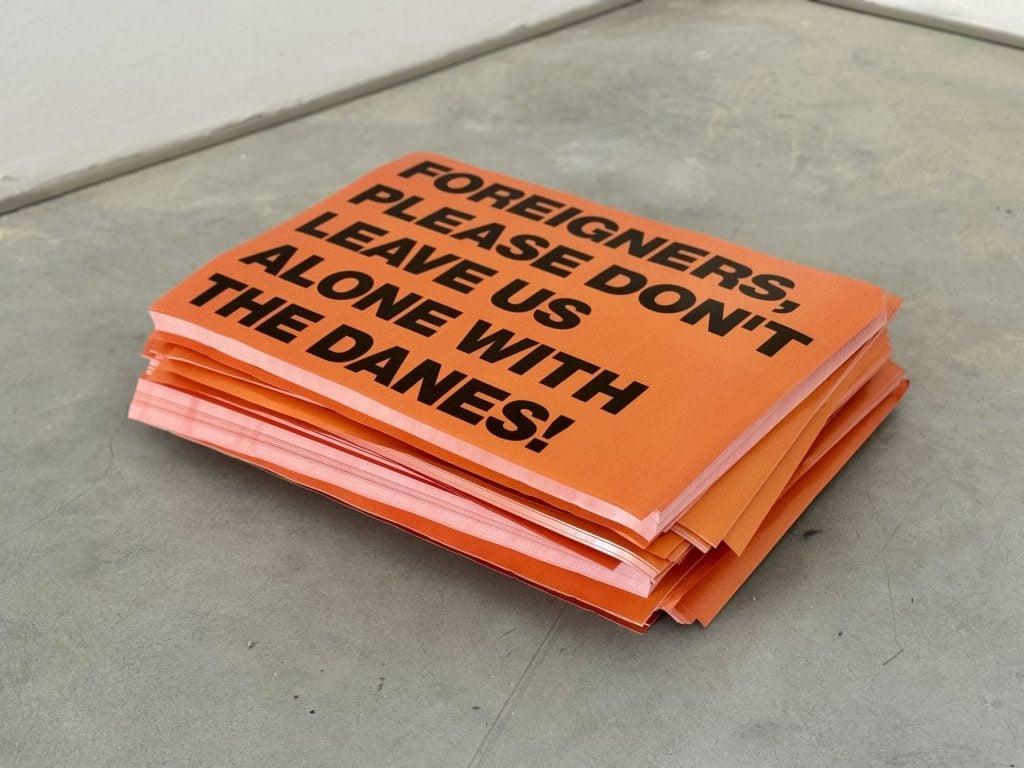

A familiar presence at many recent biennials, the Danish art collective Superflex is represented in “Foreigners Everywhere” in a small gallery up from Ferrini’s anti-Berlusconi installation. A pile of posters recalls a project from 2002 that the group put out with the slogan, “FOREIGNERS, PLEASE DON’T LEAVE US ALONE WITH THE DANES!”

It’s a cheeky bit of pro-immigrant agitprop, and Pedrosa clearly admires the group’s success in making the slogan part of the public conversation: An accompanying video rapidly cuts together images of the black-on-orange Superflex posters hung in dorm rooms and cafes. You might even guess, since Superflex’s slogan chimes with the artwork that gives this Biennale its name, that it serves as a best-case scenario for what art’s positive impact on politics might be.

And I do appreciate the spirit of Superflex’s work—but if we take its subject matter seriously, we should dig a little deeper than just celebrating the poster’s sentiment.

Superflex, Foreigners, Please Don’t Leave Us Alone With the Danes! (2002). Photo by Ben Davis.

After all, in the 22 years since Superflex conceived the poster, Denmark has taken a harder and harder line on immigration. “The Danish case offers a vivid example of how far-right ideas are flourishing, even where the far right has struggled to gain power,” the Washington Post reported last year. Denmark has served as the role model for increasingly punitive immigration regimes across Europe. One activist told the Post, “When I tell them what we are doing, people don’t believe me. They say, ‘We Danes don’t treat people like that.’”

Truly pondering the meaning of Superflex’s historic poster, then, should be chastening. It should make us think that the act of making clever statements about the value of diversity, even when are as viral as an artwork be, is not really a match for the actual forces eroding the “cosmopolitan” cultural consensus. It should make us beware of the false comfort of art shows.

I’ll conclude in Part 3 with thoughts on what the 2024 Venice Biennale suggests about the state of the art world in general.