Politics

From Pots to Posters and the Press, UK Artists Use Everything They Can to Oppose Theresa May

With polling day just two days away, artists like Jeremy Deller, Grayson Perry, and Banksy are having their say.

With polling day just two days away, artists like Jeremy Deller, Grayson Perry, and Banksy are having their say.

Hettie Judah

Over the weekend of May 20, posters reading “Strong and stable my arse” were covertly pasted up around London. The work of Jeremy Deller—whose art has previously probed issues of popular protest, political engagement, representation, propaganda, and hypocrisy—the posters were unsigned, but made plain reference to British Prime Minister Theresa May’s “strong and stable” slogan, parroted during recent campaign speeches.

Deller is not alone in adding his voice to the clamour surrounding the upcoming British election. Indeed, the art world’s involvement has been unusually—one might say exceptionally—fervent. Perhaps it was the forceful bursting of the bubble that surrounded liberal (social) media following the British EU Referendum and US presidential elections last year, but something has galvanized creative engagement both with the process itself and with the new modes of communication that have emerged in its slipstream.

“I’m very interested by all the Photoshop and animation that’s grown up around Trump and this election, the power of the image is huge and has returned,” Deller, who admits that the attention garnered by his posters came as a great surprise, told artnet News.

Jeremy Deller in Liverpool, England, on June 1, 2017. Photo OLI SCARFF/AFP/Getty Images.

Like the rest of us, the artist enjoys a good Trump and Merkel meme encountered online, but for his own project, Deller went low tech, producing a printed poster rather than an artwork to be passed around on social media.

“I grew up seeing a lot of posters in the street—it was how I got my information. If you put a poster up in the street, it’s going to be seen by everyone, especially if it’s quick to read—there’s no point in just speaking to people who will agree with you and share it online,” he explained.

Other artists have been pulled into the election circus by happenstance. As a public figure and TV personality in the UK, Grayson Perry has attained popular status, somewhat at odds with the spiky, vanguard cool of London’s Serpentine Gallery. That the Serpentine was to hold a major Grayson Perry exhibition—conspiratorially titled “The Most Popular Art Exhibition Ever!”—was surprise enough in itself.

A TV documentary crew followed Perry as he prepared a new suite of works inspired by Brexit, and all was fun and games, as they say, until a snap election was called for June 8, the date of the show’s opening.

The election has given Perry’s exhibition—which was prepared in the real-time run up to polling day—a different heft. Overnight, the artist’s glaze and thread depictions of the various divisions underlying British society have acquired the status of important political commentary and analysis. With his pots, weavings, and modified motorbikes, Perry’s work itself has, whether he likes it or not, become part of the broader cultural tapestry surrounding the British election.

Grayson Perry, Matching Pair (2017). Photo Robert Glowacki, ©Grayson Perry, courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro, London.

In late April, shortly after the opening of her Frith Street Gallery show inspired by the US elections, Cornelia Parker was appointed official Election Artist by the House of Commons. Parker has since hunkered down with the press corps, sharing train carriages with political hacks and following MPs on the campaign trail.

While her known affiliation tends Green, Parker’s temporary role is broadly non-partisan, leading her to reflect not only on pressing political issues such as social care, but on the entire election infrastructure, and real life happening beyond.

Her @electionartist2017 Instagram account offers idiosyncratic coverage, with Parker’s eye drawn as easily by stacked newspaper headlines and manifesto launches as it is to flashes of colour on the street, spilt milk, leaning trees, and cats. (Should you ever worry that the UK art world is insufficiently self-regarding, her photostream also includes a portrait of Perry, and an image of one of Deller’s posters.)

Deller’s samizdat flyposting and Parker’s Instagram turn both reflect the growing power of alternative media in the election process, from the widely reported Grime4Corbyn campaign, to the gross-out glee of the Wankers of the World “Political Whores” flyers anonymously plastered inside London’s phone boxes.

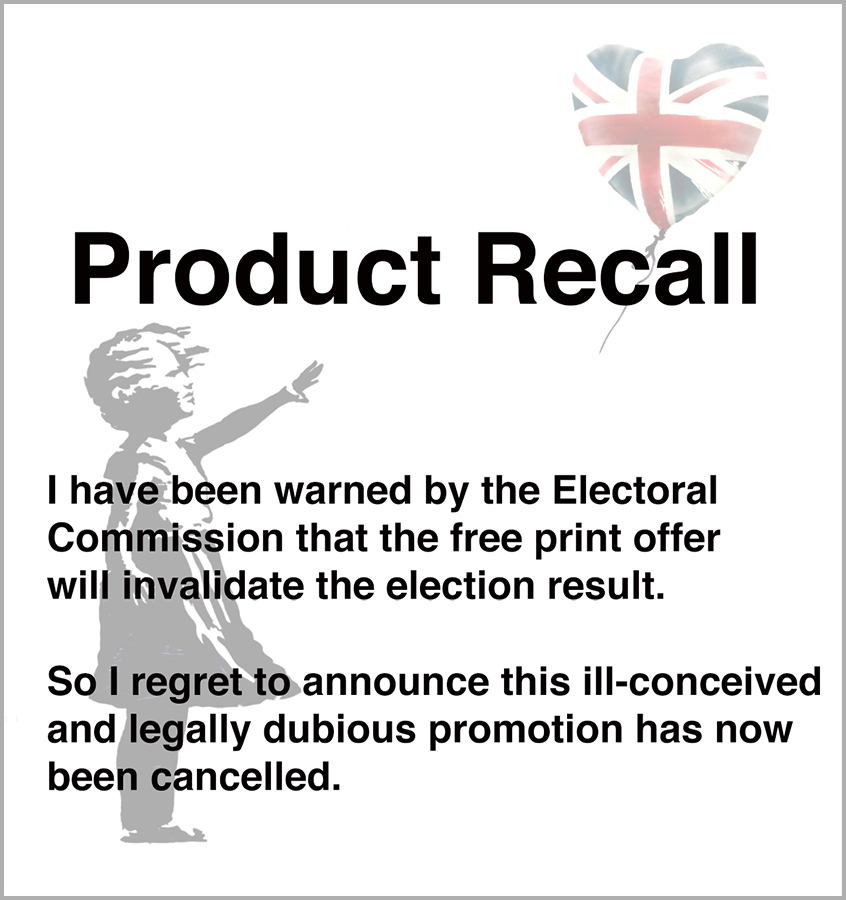

Even Banksy has weighed in, with his offer of a free print for verified votes against the Conservatives in the Bristol region, which spread like a sneezing fit across Facebook and Twitter over this last weekend. (This morning the artist withdrew the free print offer, claiming to have been warned by the Electoral Commission that it would invalidate the election result.)

The announcement posted on Banksy’s website this morning.

Of course, the art world is as dependent on Britain’s National Health Service, education, welfare, security, and transport systems, as the rest of the population, but there are areas of policy that are particularly keen. Among these are issues that affect the viability of London and other major cities as sites for making art, and the possible impact of a hard Brexit on the increasingly cosmopolitan cultural sector.

“Brexit is obviously not just about politics, there will be cultural changes as well,” the London-based Turkish artist Işıl Eğrikavuk told artnet News.

Eğrikavuk’s experimental dining work Pluto’s Kitchen was performed last week as part of London’s performance festival Block Universe. Likening Britain’s exit from the EU to the disintegration of a love affair, Eğrikavuk penned a series of break-up letters to be performed by an international, London-based cast.

Pluto’s Kitchen by Işıl Eğrikavuk, commissioned by Open Space Contemporary and Block Universe at the Ned, London, 2017. Photo ©Arron Leppard, courtesy Block Universe.

“On our first rehearsal, we all talked about everyone’s visa situation and realised how precarious everyone was feeling regarding their status here in the UK… I think everybody is relating to it on some level, whether personal or political, so much that people really can read it from the heart,” said the artist.

Accompanying the performance, the Pluto’s Kitchen menu was structured according to the stages of a relationship: stimulating, heartwarming, but ultimately ending in a (quite literal) pickle.

Meanwhile, the London-based photographer Uta Kögelsberger launched her mail art project Uncertain Subjects on June 2, timed to coincide with the final sprint before election day.

“You have to take it on when things are shifting so radically: you can’t just pretend that you’re not a part of that,” Kögelsberger, who feels that the platform and visibility afforded her as an artist make it imperative to take a stance, told artnet News.

The artist Melanie Manchot, one of the Uncertain Subjects of Uta Kögelsberger . Courtesy the artist.

“People were not doing enough [in Germany] in the 1920s and there’s so many parallels now. It’s our responsibility to do something as public figures. If we don’t then who’s going to do it?” she added. (Like Deller, Kögelsberger views her public response to the election as a project or intervention, rather than an artwork per se.)

Recruiting her subjects through word-of-mouth, Kögelsberger has produced a set of postcards portraying other long-term, settled, employed, and tax-paying UK residents that, like her, have non-confirmed resident status. All look vulnerable, and culturally unreadable, denuded of the othering or familiar symbols of social, economic, or national status.

Distributed online and in shops in London and Newcastle, the artist hopes that the postcards will provoke a dilemma in those that receive them in their letterboxes: “What do I do with this person that’s landed on my doorstep—do I put them on the wall? Do I put them in a pile of paper? Do I put them in the bin?”

Grayson Perry speaks as Queen Elizabeth II and Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh look on as they attend a reception and awards ceremony at Royal Academy of Arts on October 11, 2016 in London, England. Photo Jeff Spicer/Getty Images.

In the Channel 4 documentary Grayson Perry: Divided Britain, aired ahead of the Serpentine show, Perry referred to the idea of a voting public divided between the people of anywhere and the people of somewhere. It’s an idea first posited earlier this year by writer and theorist David Goodhart in his book The Road to Somewhere, which divided the political map less along traditional party political lines than between the Anywheres—cosmopolitan, tech-savvy, citizens of the world—and the Somewheres—those whose sense of identity was lashed tight to a sense of both geographical and community belonging.

The Road to Somewhere would place the art world quite firmly in the camp of the Anywheres. By that logic, in engaging with the election and its attendant issues, the challenge for artists is to communicate with the Somewheres. While they may have done so by very different routes, stepping up to this challenge has been a driving imperative for both Perry and Deller.