Politics

Meet the Artist Whose Job Is to Paint Epic Portraits of Julian Assange inside the Ecuadorian Embassy

One of George Gittoes's portraits of the WikiLeaks founder is up for an Australian art prize.

One of George Gittoes's portraits of the WikiLeaks founder is up for an Australian art prize.

Sarah Cascone

Among the few visitors permitted to see WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange in the Ecuadorean Embassy in London, his refuge of the past five years, is the artist and filmmaker George Gittoes, who has been painting portraits of the controversial computer programmer-turned-whistleblower since 2014.

Most recently, Gittoes entered an ambitious seven-foot-tall diptych of Assange, painted at the embassy, into this year’s Archibald Prize, an esteemed annual award for portraiture in Australia, handed out by the Art Gallery of New South Wales. Although Gittoes did not win, he has gone on to submit a second version of the portrait to Australia’s $150,000 Doug Moran National Portrait Prize, where the work has reached the contest’s semi-finalist stage.

The portrait sessions were mentioned in a recent New Yorker profile of Assange, who became a fugitive in 2010 after publishing classified military documents leaked by army soldier Chelsea Manning (then Bradley Manning) on WikiLeaks under the title Collateral Murder.

More recently, the site’s activities during the 2016 election, publishing emails and documents illegally obtained from the Democratic National Committee, have come under scrutiny for possibly having originated via hacks by the Russian government.

Artist George Gittoes with his paintings, including that of Julian Assange, on the roof of the Yellow House art center in Jalalabad, Afghanistan. Courtesy of the artist.

Assange first invited Gittoes, a fellow Australian, to visit the embassy in 2014. The artist initially worried that any association with Assange could inhibit his ability to work in war-torn countries. A recipient of the 2015 Sydney Peace Prize, Gittoes runs the Yellow House art center in his current home of Jalalabad, Afghanistan, with his wife, Hellen Rose. (Gittoes also co-founded the historic Sydney gallery and art collective of the same name in 1970.)

“Being linked to Julian when I’m about to step back into the front line could be lethal,” he wrote in his recently published autobiography, Blood Mystic.

Nevertheless, the artist accepted the invitation because, he said, “I never question destiny.” Gittoes brought his art supplies with him, and soon was hard at work on what would become the first in a series of portraits.

The recent diptych is meant to depict Assange’s willingness to take risks, and to live as a true “edgewalker”—Assange’s word—showing him gazing over the edge of a mirrored precipice. The second panel repeats Assange’s face over and over, as if seen on computer screens, in a commentary on the contradiction of his simultaneous digital omnipresence and physical containment.

George Gittoes’s painting of Julian Assange, painted at the Ecuadorean Embassy in London. Courtesy of the artist.

Painting the work was a challenge under the circumstances. “I thought that it could annoy the embassy staff to take oil paints, with their smell of turpentine, into such a small and un-ventilated space,” Gittoes wrote in an email to Artnet News. “Not wanting to make Julian’s tenancy any more difficult,” he used gesso instead—not his typical medium.

The artist’s 2017 Archibald bid, along with that of seven other competitors, is the subject of a four-part Australian documentary series The Archibald, from Mint Pictures. (Like any good reality show, each star gets an introductory catchphrase. Gittoes’s is “I don’t think there’s anyone you’d ever want to paint that you’d take a bullet for—but I’d take one for Julian.”)

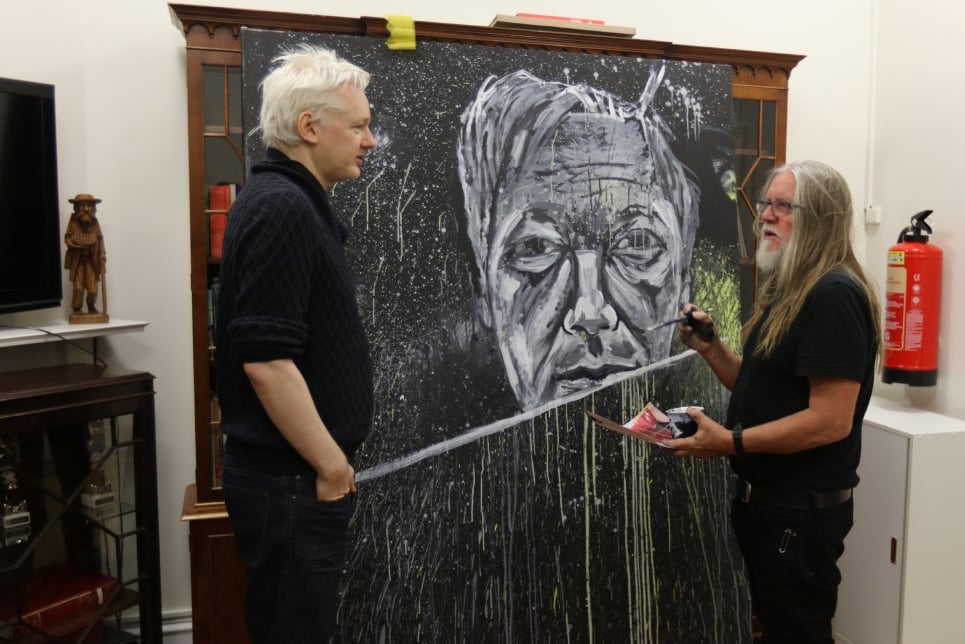

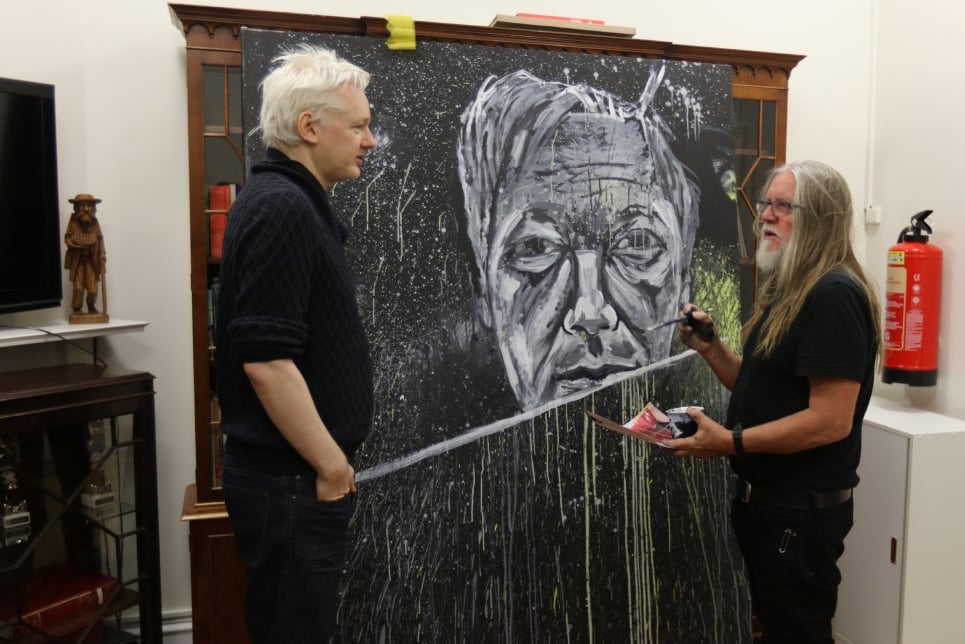

Artist George Gittoes with Julian Assange at the Ecuadorean Embassy in London. Courtesy of the artist.

The production limited some of Gittoes’s plans for the painting. Originally, he planned to take the work with him to Afghanistan, where he would incorporate oil paint into it. “The film company lawyers were not prepared to take the risk of the painting being lost or damaged in transit to and from Afghanistan—also, of me being killed,” he recalled.

But it was thematically and conceptually important to both the artist and the subject to finish the piece in Afghanistan, so Gittoes went on to repaint a near duplicate version of it on the roof of the Yellow House in Jalalabad, which “is in the flight path of US combat helicopters and unmanned drones,” he said.

“Someone must have told the US intelligence that I was there doing the painting and so helicopters began hovering over our rooftop while the crews took photos of the large face and figure of Julian as it emerged on canvas,” Gittoes added. “I imagined Julian would like this story as it meant that crews like the ones who had done the callus and undisciplined shooting in Iraq [disclosed in WikiLeaks’s Collateral Murder leak] were now seeing the portrait.”

George Gittoes’s second painting of Julian Assange, painted on the roof at the Yellow House art center in Jalalabad, Afghanistan. Courtesy of the artist.

Asked to choose a favorite between the two versions of the composition, Gittoes demurred: “Both have special qualities—one for being painted from life with Julian and the other for being painted in an active war zone.”

Back in London, there was much talk of how the artist’s sessions with Assange would be portrayed in the television series. “There cannot be an image of Julian Assange looking at himself in a painting. That’s madness—absolute madness,” Assange insisted in the New Yorker. He also refused to compliment the work, claiming that would be vain.

Artist George Gittoes with Julian Assange at the Ecuadorean Embassy in London. Courtesy of the artist.

Gittoes seemed surprised that the Archibald’s 11-person board of trustees did not select his portrait of Assange as one of the 104 finalists (from 822 entries). “I have been hung many times in the Archibald, so it is very unusual for the portrait not to be hung,” said Gittoes, who was previously a finalist in 1997, 1995, 1994, 1993, and 1991/92. “This is my second attempt to get a portrait of Julian hung in the Archibald. The first version, a couple of years ago, was also rejected.”

“The gallery is not privy to the reason why George’s work was not selected this year,” a spokeswoman for the Art Gallery of New South Wales told artnet News in an email. “George is well known in Australia for his socially engaged and highly political paintings, drawings, prints, and film works, made since the late 1960s. His work is held in the gallery’s permanent collection and works we have demonstrate his political engagement.”

Artist George Gittoes with Julian Assange at the Ecuadorean Embassy in London. Courtesy of the artist.

Gittoes readily acknowledges that there’s a legitimate reason that Assange is such a polarizing figure. “The reason why I support Julian and see him as an inspiration is very simple,” he told the New Yorker. “He proves that one individual can still stand up against the powers we all feel oppressed by.”